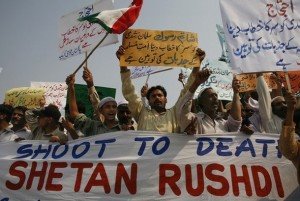

This past Saturday marked, besides St. Hallmark’s Day, the 20th anniversary of the Rushdie affair during which Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued the most famous modern-day literary death sentence, a fatwa upon the head of British writer Salman Rushdie for his allegedly blasphemous novel The Satanic Verses. Khomeini’s issuance of the fatwa was a turning point for the Western world in terms of free speech and the possible impact of art derived from post-colonial democracies. The order for the life of Rushdie and all involved in his work infused, or rather re-infused, the literary world with excitement and fear in knowing that words still can, even in the democratic west, incite fear and reaction.

This past Saturday marked, besides St. Hallmark’s Day, the 20th anniversary of the Rushdie affair during which Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued the most famous modern-day literary death sentence, a fatwa upon the head of British writer Salman Rushdie for his allegedly blasphemous novel The Satanic Verses. Khomeini’s issuance of the fatwa was a turning point for the Western world in terms of free speech and the possible impact of art derived from post-colonial democracies. The order for the life of Rushdie and all involved in his work infused, or rather re-infused, the literary world with excitement and fear in knowing that words still can, even in the democratic west, incite fear and reaction.

Akin to Ovid’s banishment to the Black Sea, Dante’s exile from Florence, and many others, Salman Rushdie will go down quite romantically with the rest of history’s high-profile exiles. (Did you know that Atonement’s Ian McEwan harbored Rushdie in his cabin in the Cotswalds just after Khomeini’s sentence? How cinematically saccharine.) When I interned for the PEN American Center in college, Rushdie was the figurehead president of the organization (which does admirable work, by the way, defending free expression and highlighting some of the world’s most wonderful marginalized writers) and in terms of the fatwa affair–although he is a supremely talented creator–I see Rushdie’s position as similarly nominal. After all, the image of the writer in exile is, historically, one rich in literary tradition and wholly necessary in upholding the notion that free speech and liberal knowledge is ultimately indomitable. But Rushdie was never going to be hurt: he’s way too culturally indispensable to the West. The people who actually did sacrifice it all to literature will not be remembered quite as clearly, if they are thought of at all.

According to the affair’s Wikipedia page , Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator, was stabbed to death on July 11, 1991; the Italian translator was also stabbed, although he survived with serious injuries; Aziz Nesin, the Turkish Satanic translator, was targeted in July of 1993 in the events that resulted in the Sivas massacre during which 37 Turkish intellectuals were killed; and William Nygaard, a publisher in Norway, barely survived an assassination attempt.

I am unclear as to why the memory of these incidents doesn’t go hand-in-hand with that of Khomeini’s initial issuance. It’s regrettable that upon the anniversary of the infamous fatwa, despite various candid analyses of the the sentence’s legacy upon Western literature, little mention is made of the individuals who truly did risk and lose their lives in substantiating the momentous import of innovative words and free ideas.