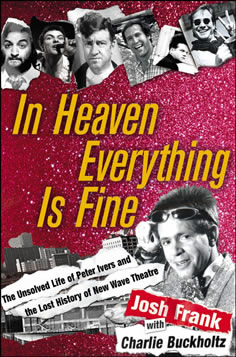

Free Press, Reviewed by Matthew Caron

In Heaven Everything Is Fine examines the “unsolved life” of Peter Ivers, a man who was seemingly many things to many people and who managed to be at the center of several major scenes without managing to become a star in his own right. Although the book’s subtitle reads as The Unsolved Life Of Peter Ivers and the Lost History of New Wave Theater, Ivers is correctly identified early on as being best remembered for writing and singing “In Heaven”, the enigmatic siren song of The Lady In The Radiator in David Lynch’s “Eraserhead” from which the book takes its title. Author Josh Frank found his way to the threads of Ivers’ life story through his previous book, a history of The Pixies, whose cover version of the song is arguably more popular that the David Lynch film it is taken from. Once Frank began to investigate the backstory of this song, a larger story about the songwriter revealed itself, one which illuminated a lost history of L.A.’s showbiz elite in the 70s and 80s and its run-ins with the artistic and musical underground. What Frank and collaborated Charlie Buckholtz have managed to excavate through a series of candid interviews is the story of a type of facilitator who must surely exist in every great cultural moment. Peter Ivers was an accomplished artist and musician in his own right, but it is his legacy as a consummate networker and cheerleader that continues to fascinate and which justifies the book’s existence. In Heaven Everything Is Fine sketches a genealogy of important events in pop culture and illuminate relationships, friendships and tensions that would remain invisible without a consideration of Peter’s ample contributions. Players like Peter are usually consigned to remain at the periphery of history, but authors Josh Frank and Charlie Buckholtz have done something unique in placing Peter at the center of this history. In doing so, they have saved Peter Ivers from oblivion, or at the very least raised him from the status of a mere footnote to that a very important footnote.

Besides “In Heaven”, Ivers is best remembered as the irreverent and verbally acrobatic host of the early 80’s Los Angeles cable program “New Wave Theater” where he would routinely probe his guests in search of the meaning of life.

Peter Ivers Interviewing Lee Ving of Fear on New Wave Theater:

PETER: What is the meaning of life?

VING: The meaning of life is…the meaning of life is…to stay gay all the way.

PETER: Well, then, you have succeeded. Lee, what do you hate least in the world?

VING: Not you.

Immortal words. However, New Wave Theater is only a small part of the story which unfolds late in the telling. To blues aficionados, Ivers is remembered as one of the greatest harmonica players of all time, singled out at the master by no less an authority than Muddy Waters, who briefly recruited Ivers as a member of his band. To pop afficionados, Ivers was a musical sensation in his own right, producing several albums of offbeat pop music sung in a love-it-or-hate-it high-pitched nasal sing-song. To scholars of comedy, Ivers is the best friend of National Lampoon founder Doug Kenney and kept company with John Belushi, Harold Ramis and Bill Murray. These great comics found their way to the set of New Wave Theater to crack wise and rub elbows with the punks, relishing the opportunity to play hooky from the TV programs and films that made them millionaires. Meanwhile, the happy host never earned a cent from the show. Peter used his unique position in the Hollywood pecking order to orchestrate the friendships between Belushi and Fear, and between David Lynch and Devo, who made “In Heaven” a staple of their late 70s concerts with Lynch’s personal blessing. Prior to this exhaustive biography, these strands remained unconnected, and so it was that this man who was fiercely loved and valued by his famous friends remained all but unknown to the world at large.

Because the book tries to cover so much material adjacent Peter Ivers’ life, it’s inevitable that the passages of pure biography are less exciting than the histories of the scenes he circulated in. He remains a supporting character in his own story, the most interesting portions concerning themselves with National Lampoon founder Doug Kenney, who would take refuge in Peter’s company at times when showbiz got under his skin, which happened to be very frequently. After Doug’s addictions and frustrations finally drive him to suicide, Peter’s life begins to take a turn for the worse, underscoring the fact that he was so thoroughly defined by highs and lows of the company he kept. One can only imagine the feelings of a man whose friend finds success in the very fields where he has not, only to wind up choosing death. The final chapters of this story feel ominous and dark not only because we know Peter is doomed, but because the circumstances of Los Angeles in the late 1970s and 1980s are rendered as particularly bleak in comparison to the past. Doug Kenney’s out, Fear’s in.

Even with friends in high places and the popularity of New Wave Theater, Peter never managed to “make it” in Hollywood, and his struggles with poverty are a major part of the story. This last detail is the critical piece in the story leading up to his death. Peter’s final residence was a low-rent loft in L.A.’s notorious Skid Row where only a cheap lock separated him from a dangerous mileau of crime and drugs. The lock proved fatally inadequate at keeping Ivers safe. Early in the morning on March 3rd of 1983, someone entered Peter’s apartment and beat him to death with a hammer. The killer was never found, but Frank and Buckholtz’s work has resulted in the LAPD reopening the case. It’s fitting and satisfying that the substantial amount of detective work by Frank and Buckholtz in telling the story of Peter’s life has resulted in the authorities taking an overdue interest in the events surrounding his death.