Posted by Tobias Carroll

In the end, it’s the messy works that get me: the movies and books that should not under any circumstances work and yet do; the idiosyncratic works are the ones that invariably burrow into my subconscious and stay there for years. This happens with films a lot: Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain might be the apex of this: watching it is a deeply subjective experience (even moreso than the watching of most films), and it’s less the promised work of science fiction than a deeply personal, highly intimate work about grief. Tarsem Singh’s The Fall is similar: it’s at once an adventure story and a film about storytelling, one in which multiple tellers revise and reimagine the same narrative. I expect that if I revisited Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, I’d have a similar experience. It’s almost impossible to evaluate these films empirically: they create their own groundrules; their narratives work on their own terms.

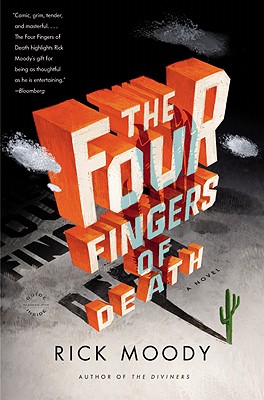

All of this is a deeply roundabout way to say that my thoughts on these films are not far removed from my thoughts on Rick Moody’s The Four Fingers of Death, which I just read in paperback. Or maybe it’s not — the bulk of the novel is, after all, a novelization of a remake of a 1960s horror film, so there’s cinema in its DNA. Ostensibly.

From looking at a capsule description of the novel, I’d been wary at first: the book before us focuses on a writer named Montese Crandall whose method of editing generally leaves him winnowing novellas down to single sentences. Crandall ends up writing the novelization mentioned above, which fills most of the book. In other words, the bulk of this novel is comprised of the novel within the novel. Admittedly, The Ice Storm established Moody’s fondness for the pulpier side of science fiction. (I suspect it’s no coincidence that characters in Four Fingers have the surnames Stark and Richards.) And his novella “The Albertine Notes,” set in a ruined Manhattan, is a fine and elegiac work of science fiction. Still, the nestled narratives and roots in a film riffed on by MST3K left me skeptical.

And all of that is an even more roundabout way of saying that my skepticism was painfully unwarranted. This is a long book that, more or less, works as three distinct books affixed together (something Crandall points out to the reader partway through.) Contained here are a tense spacebound conspiracy thriller, a more comedic work laced with apocalyptic horror set in a near-future Southwest, and the framing story, Crandall’s own. And it’s only when you reach the end that you realize the extent to which Crandall’s own experiences have suffused the novel within the novel: the parallel stories, the narratives in tandem with the arc of his own life.

A sense of despair pervades the opening section: the health problems of Crandall’s wife, his fondness for physical objects in an increasingly digital world, the ebbing fortunes of his country, the economic hardships that seem to surround him.

And yet. Ultimately, Crandall finds the moments of humanity within a mediocre sci-fi/horror narrative; he reaches out and makes that declaration and, in doing so, becomes heroic. The ending of the novel, in which the full structure of everything we’ve just read is revealed, left me sitting on my couch, devastated. This doesn’t resemble much of Moody’s earlier work as much as it shared certain qualities with Michael Kimball’s Us and Dear Everybody — books that also lay develop along unexpected lines and via quietly unconventional structures.

2 comments