Posted by Tobias Carroll

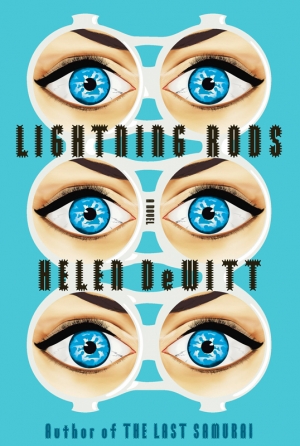

It’s been a few weeks since I finished Helen DeWitt’s second novel, Lightning Rods. Jen Vafdis contributed a fine review of the novel earlier this week; I wanted to throw in my two cents here, as this is a novel that seems designed to spark debate, inspire discussion, and leave the reader just more than slightly unmoored.

I’d approached Lightning Rods the way, I suspect, many fans of DeWitt’s earlier novel The Last Samurai did, and consequently wasn’t expecting its much more satirical tone. Aside from the precision with which it’s been written, I don’t know that there’s much in common between the two novels. Which isn’t to say that I wasn’t impressed — for all of its seeming breeziness, many aspects of Lightning Rods have gotten under my skin.

There’s a lot to talk about here — the novel’s satire of corporate doublespeak; the way in which DeWitt’s structure addressed a lot of the critiques I had of the novel as they arose; the significant differences in tone and style between this and The Last Samurai. One of the things that struck me most came in DeWitt’s Acknowledgments section — specifically, her invocation of The Producers. I’d seen the novel’s comedy in more of a Preston Sturges vein — albeit one with a far more cynical central conceit. (To say nothing of anonymous sex in office restrooms.)

Much of what makes the novel work is the appeal of its central character, an ambitious Everyman type named Joe. On the one hand: yes, he’s someone who starts a business based on his own idle sexual fantasies. But he also possesses a core of idealism — which might explain why the subplot about his creation of an adjustable toilet (designed for people of any size and shape) is in there. He makes his way through the world with a strange measure of haplessness and uber-competence, but neither extreme felt unbelievable.

Given that this ends up being a novel focusing on a fundamental transformation of society, I also found myself wondering if Lightning Rods ends up being Helen DeWitt’s response to some of the work of Michel Houellebecq. The same basic plotline (hapless man joins with uber-competent woman to fill an unspoken societal need) could have worked as a followup to, say, Platform — albeit with a tragic tone instead of a (mostly) comedic one.

Emphasis on that “mostly,” though. Throughout the book, DeWitt is adept at addressing readers’ unspoken concerns as they arise. And in the end, her satirical novel is unafraid to leave society fundamentally changed, its final note impeccably ambiguous.