Interview by Tobias Carroll

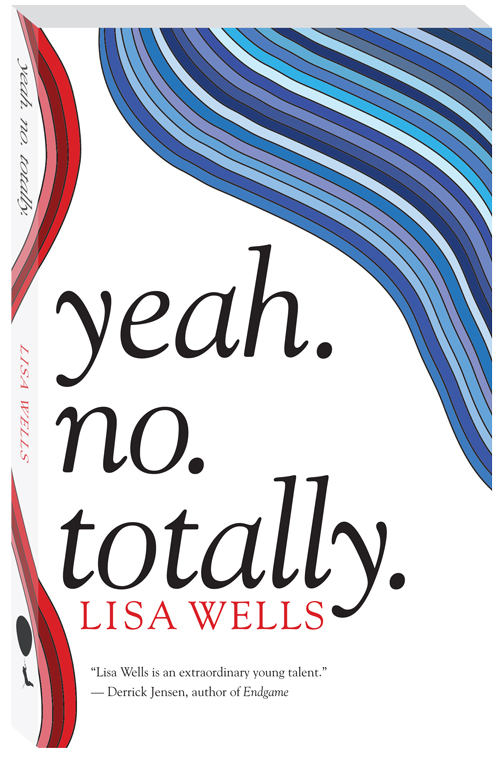

As we head into the middle of November, I think it’s safe to say that Lisa Wells’s collection Yeah. No. Totally. (released by the Portland-based indie press Perfect Day Publishing) is a safe bet to be recorded as one of my favorite books of the year. Through the work collected here (mostly essays, with one short story — more on that balance below), Wells examines the city in which she lives through various manifestations of culture there. Sometimes, that window comes through her experiences as the daughter of a rock drummer; in others, it’s via sharp observations of video games and barely suppressed trauma. It’s an excellent debut (and an excellent read, period); after reading it and seeing Wells read at Book Thug Nation earlier this fall, I checked in with her via email to discuss this book and what’s to come.

Several of the essays in Yeah. No. Totally. touch on music in some form or another. To what extent does music (and other forms of art) affect of influence your writing?

I’d say I’m pretty influenced by music, and by film, albeit to a lesser extent. My parents met in a band. Growing up we always had degenerate musicians living in our basement or garage. To this day my dad plays drums in a metal band, so rock music has figured in my subconscious nearly as prominently as my own mother. I started going to shows regularly at 12 years old, a little after the Portland scene started heating up, so it was present in my home culture and in the larger culture. Also, I consider myself a poet first, so there’s a relationship with music via syntax. In that way it operates on two levels, as a subject and as a guide for construction. I think a lot about film when I’m working on structure, establishing shot, medium, close-up, etc.

What first provided the impetus for you to start writing?

Well, to be totally boring, I’ve always written. I kept regular journals as early as the 2nd grade. I still have a poem from that time based on a character from General Hospital (which my mom watched religiously.) The character was a lawyer in the process of being disbarred so the poem was full of all this legalese. It was called “If I had a Rebuttal”. Can you believe that? They should have forced me to play sports.

Writing was the only thing people seemed to think I was good at so I stuck with it. My dad’s been trying to teach me to play drums since I was in utero but I’m no good. My rhythm is just off enough to drive the listener insane.

Did having a parent who was actively involved in the arts have an effect — pro or con — on the process of you becoming a writer?

Good question. I think having frustrated artists for parents helped propel me into the arts. My dad was a carpenter and welder by day, he’d pull 12 hour shifts tearing out insulation or welding in the guts of these Naval Destroyers down at the shipyards. Drumming is physically demanding, who wants to get behind the drums after a day like that? You want a beer and a shower when you’re done. But dad’s work was spotty so my mother gave up the band and her theater career once she had a family. She worked overtime in customer service to feed everybody. In the end they went broke and split up, but somehow the message was never ‘get a steady job’, for better or for worse. There was a movement that was never completed, for both of them, and they live with that feeling of not having completed it. You don’t need to be Freud to theorize how that might have driven me. Who knows, maybe I was meant to be an accountant.

I have friends who grew up with high-achieving parents and not one of them has been able to move out from under their shadows. It’s a much more intimidating set up.

Portland plays a significant role in the pieces collected in your book. Do you think your work would be similar if you were based elsewhere?

Yes, and my new book is about struggling rural towns in Oregon. Thankfully, people like Jon Raymond have been updating what it means to write about this region, it’s not all flannel coats and poems about fog lifting from a field (though I love that stuff too). Would my work be similar if I came from somewhere else? Probably not, but I’d move for more money.

Yeah. No. Totally. closes with a short story. Have you been writing more fiction in recent years?

I spent a year writing a novel that turned out to be garbage. Shortly after, Perfect Day gave me about two months to produce a draft of Yeah. No. Totally. It was on shelves six months later. I can’t tell you what a relief that was. The fiction story was the only finished piece I came in with but even that was thinly veiled autobiography. In real life I lost my crackers when three of my friends died in a car crash (this was the tragic end of The Exploding Hearts), on the page they were collapsed into one character. Through writing the novel I realized that I’m not a good fiction writer, I don’t want to write fiction, and I don’t have to! Why bother when there are so many great books being written by people in love with the form? To me it always felt like a chore. My generation was burned by all those salacious memoirs born of the 80s. There was pressure to write literary fiction, as if it were the only legitimate form. I love David Shields and his manifesto Reality Hunger for taking on these issues.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and our Tumblr.

1 comment