My first recollection of experiencing Edward Gorey’s work came when I was a kid, when I kept watching PBS long after my block of Sesame Street and Mr. Rogers was up. There was a man in a suit that talked for a few moments about becoming a member of the station, then all of a sudden this odd cartoon came on and I was transfixed until it was over and some people with English accents started talking. After that I vainly tried to watch Masterpiece Mystery in hopes that it would come back on, but it never did.

I’m willing to bet there are plenty of people my age who have the same story, and it’s the reason we like Lemony Snicket books and Tim Burton’s early work. Gorey was an original, and his legacy will continue to delight and disturb us for years to come.

A 2005 Chicago Reader article points out that while macabre, his style also shows great reverence for the familial bond. I can only guess that Gorey, an only child who was reportedly smothered by his adoring mother, drew plenty of inspiration from his own extended family. He had a fine imagination for the puckish antics of children, like his Gashlycrumb Tinies that are all about to meet their doom, but they’re doing so because they’re hanging out on the train tracks, playing with fire; or like Zillah, doing a little bit of underage drinking. I’m not saying the kids in Gorey’s work are role models, but they know how to have fun.

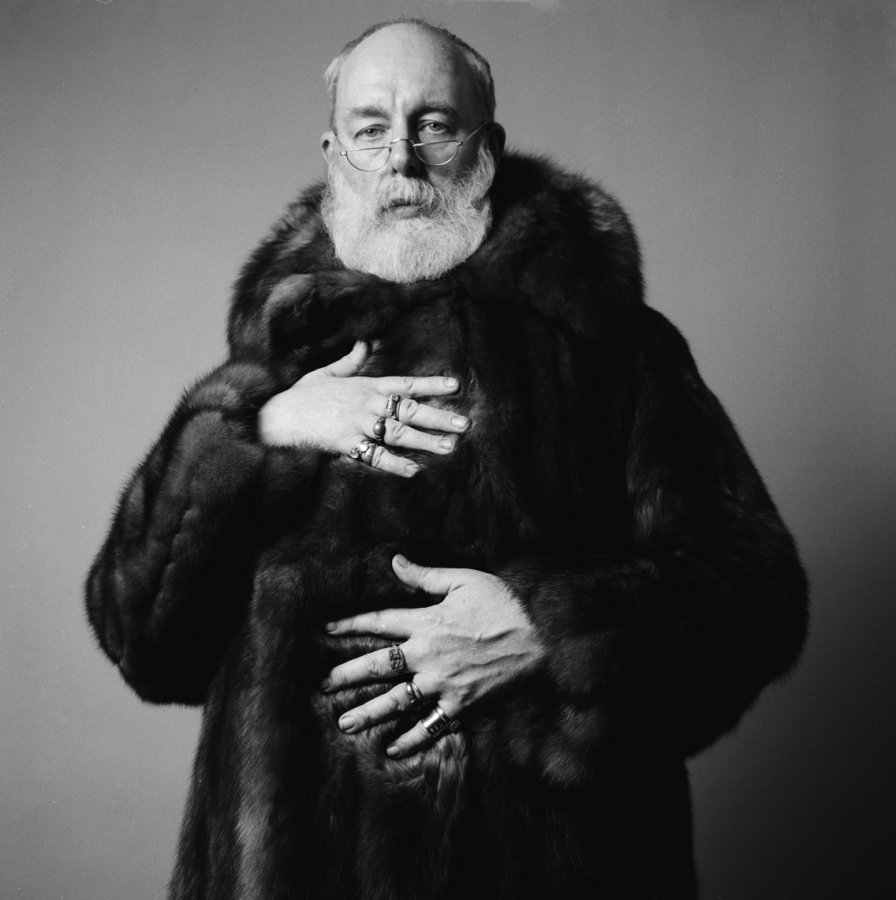

I’ve also read numerous bits and pieces about what Gorey fancied throughout his life: Buffy The Vampire Slayer, Jane Austen, and fur coats (I’d highly suggest reading A. N. Devers’ Paris Review piece for more on this), and his work extended well beyond books and the iconic Masterpiece Mystery opening, including being put to music by composer Michael Mantler, and gracing the program covers for the New York City Ballet (of which he was quite fond of).

Edward Gorey’s work is instantly familiar to me. It fills me with the same sense of happiness from my childhood that the work of fellow Chicagoan/artist/eccentric Shel Silverstein does. And just like Silverstein’s work, Gorey’s canon still seems just as subversive and strange to me today as it did when I was younger.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + and our Tumblr.