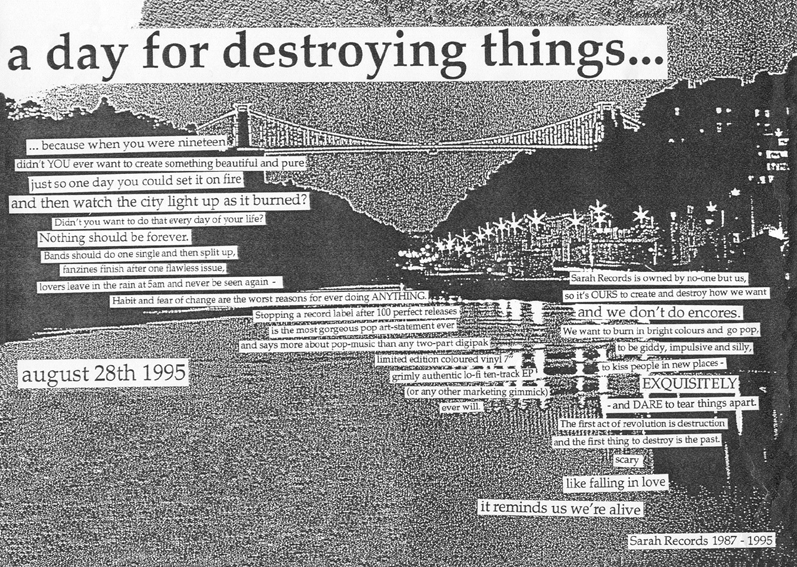

Clare Wadd and Matt Haynes started Sarah Records around the time that The Smiths called it quits in 1987. A year later Moz gave us Viva Hate and Marr found his way back to music with Electronic, but the death of the most important English band of their generation, along with the release of the famous c86 album, helped nurture the seeds of the new generation of indie pop. With releases by bands like Another Sunny Day, The Field Mice, and Heavenly, Sarah Records was the vanguard for British Indie in the late 1980’s until the founders announced the label’s demise in 1995 by taking ads out in England’s most prominent music magazines (see image above).

Canadian music writer Michael White has begun writing a book about the history of the label. After successfully meeting his goal in an online fundraising campaign, White is hard at work on the book but took a few minutes to let us know a bit more about the project

So I guess my first question is why are you writing the history of Sarah Records?

Primarily because it’s a book I’ve wanted to read for a long time and thought might otherwise never be written. Although, that said, I wouldn’t go to the effort if I didn’t think there was an audience for it. Actually, my sense of a growing interest in Sarah is what finally spurred me to start writing it after thinking about it for a long time — I began to worry that if I didn’t claim the project for myself, someone else would. And if that person didn’t do it well, I’d regret it forever.

That’s another reason why I’m writing it: I’ve almost never been satisfied with how Sarah or this type of music — whatever you want to call it: indie-pop, C86, twee — has been written about. The UK music press was mostly dismissive or outright hostile toward it when it was new. But how it’s been written about retrospectively is possibly even more disappointing to me, because it almost always lacks the sort of detail and context afforded to almost any other music considered worthy of biography. The people who have written about it in recent years, most of them experienced it when it was happening — they were there! But they don’t realize that many — if not most — of the people reading about ’80s and ’90s indie music now are coming to it late, or they lived in another part of the world, and it was at a time when the internet didn’t exist. Sarah shut down just as the ‘net was emerging, and because it didn’t receive very much press coverage, it’s very poorly documented. The result, in my experience, is that people who love Sarah — particularly people in their twenties, who are used to being able to find out everything they want to know about a band with one Google search — are completely obsessed and frustrated. They want to know everything! Hopefully this book will finally give them what they want.

How are you presenting the book? Is it an oral history, written history or something else?

It’s going to be a written history, but fragmented. To write about it as a chronological narrative wouldn’t be practical, firstly because it would take forever to write — hundreds of people were involved in various ways. And secondly because the Sarah story — and this isn’t meant as a criticism — isn’t consistently compelling. There wasn’t a whole lot of drama going on like there always seemed to be with, say, Creation or Factory; there weren’t any megalomaniacs or breakdowns or disasters — at least not that I’ve learned about yet. So I’m isolating the people and things that were interesting and giving them their own chapters. For instance, there’ll be chapters dedicated to the most popular and prolific Sarah bands — like the Field Mice and Blueboy — and also a chapter about the UK indie-pop scene that predated Sarah and essentially brought it into being, and a chapter about Sarah’s enduring and disproportionate popularity in places like Indonesia.

Who are some of the current bands you think were most influenced by Sarah Records?

I personally find it difficult to definitively pinpoint Sarah’s influence simply from listening to a new band’s music. Usually I find out it’s influenced a band when I read an interview. For instance, the Drums and the Pains of Being Pure at Heart have been very vocal about their love for Sarah, but I don’t think they sound like any particular band on the label. This is a nebulous thing to say, but I think it’s more to do with a feeling; they’re bands that love melody, and they share a sensibility that values romance and vulnerability. I don’t know for certain, but I suspect Belle & Sebastian and the Clientele must be Sarah fans as well, and several of the bands on Slumberland. Those are relatively high-profile examples though. It might be that the majority of Sarah’s influence can be found in under-the-radar bedroom projects whose music you’ll never hear unless you stumble onto the right Bandcamp or MySpace page, or you take a chance on some privately pressed 7-inch single in a local record store.

When did you first become aware of the label?

I was lucky. In early 1987, when I was 17, a bookstore in my hometown began stocking Melody Maker, and for the next eight years I didn’t miss a single issue. The early Sarah releases were reviewed on the Singles page, and although the reviews were all negative — because anything perceived as being associated with C86 was subject to a huge backlash at the time — I knew from the way they were described that I’d like them. Someone had taped the C86 album for me the previous year and I was obsessed with it, so I was on the lookout for anything similar. Eventually I found the Field Mice’s Emma’s House EP, and then I sent away for Shadow Factory, and I was on my way.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + and our Tumblr.