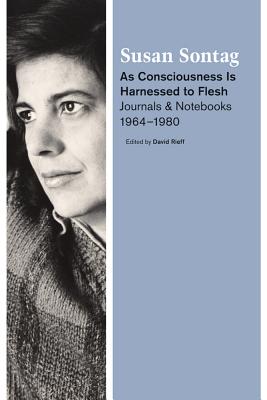

As Consciousness Is Harnessed to Flesh: Journals and Notebooks, 1964-1980

by Susan Sontag; David Rieff, editor

Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 544 p

On a Sunday afternoon a bit over a year ago, I was in the apartment of a good friend who, while reading his Wall Street Journal (his motives were pure: to better understand the financial markets and a view that ran contrary to that of his neighborhood), made a noise between a moan and gasp. He proceeded to read aloud that weekend’s review of Sempre Susan.

The line that got us going, in collective shock on a warm spring day, was as follows:

The problem is that Sontag wasn’t sufficiently interested in real-life details […] She also wrote and directed films, which were not well-reviewed: I have not seen these myself, but there is time enough to do so, for I have long assumed that they are playing as a permanent double feature in the only movie theater in hell.

My. I have no doubt that quite a few fall into this camp on the entire affair of Sontag’s work. But if you choose to tackle the second, and, arguably, juicier volume of her three chronological journals, be prepared for a treat. (The third is not yet released, but is cagily alluded to in this text’s introduction by her child, and the editor of this series, David Rieff.) It begins when she was just 31. She is, expectedly, more settled than in the volume before, and at work on the texts that came to define her career.

8/29/64

Is being tired a spontaneous complicity with death—a beginning to let go at what one judges to be about the right time, half way?

Or is it objectively so, that one would anyway be tired at 35 and spend the next 165 years “se traînant” [“moping around”]*

10/17/65

Have I done all the living I’m going to do? A spectator now, calming down.

This is pure, uninterrupted Sontag. Really, it’s the Sontag channel in quick, bursting intervals of thoughts on art, travel, lovers, and Things To Do. Her lists encompass the text like the sheaths of wrapping paper around small items. They might be compared to the apex of the Google-algorithm-ed ad, made for just the type you think would be picking the book up at the Kindle fair.

9/10/64

Do essays on:

10/3/64

A murder: like a flashbulb (panoramic photo) going off in a dark forest, lighting up all the obscure, frightened woodland life. (Dallas—Nov. 1963)

Ms. Sontag’s sentiments did not always stand her in good stead. Her post-9/11 New Yorker piece, written immediately after that event, was remonstrated for its timing. Her 1982 renunciation of Communism as she finally saw it – a form of fascism – did not sit well with many. Illness as a Metaphor, which I once read with a great deal of enthusiasm, felt a bit off my most recent time through. Such a vastly discursive approach to cancer as it then existed, with so little hope of sustained remission or concise care, seems to circumvent the cruelty of the disease’s nature.

But the pleasure of her journals is that they are not of our time; they’re of hers. And what a time it was—not simply, obviously, for the period itself, but also, naturally, for the situations to which she pushed herself. The image I have always admired positions her, in 1972, cross-legged on a sofa, wearing trousers and an overcoat draped around her shoulder. She’s smoking in a manner we would now fear (live ash over fabric), with a waning look about her. The photo belies person and persona in extremis. In the ’60s and ’70s her intellectualism was pervasive. An aesthete through and through, her personal tastes were hardly confined to the America in which she grew up (Arizona and Southern California), and veered wildly toward the European, the abstract, and the cinema.

8/20/64

Quality of film [stock] is important—whether grainy or not; old stock or new ([Stanley] Kubrick used WWII unused newsreel stock for War Room sequences in Dr. Strangelove)

[Dated only “Note from 1977”]

Best films (not in order)

1. Bresson, Pickpocket

2. Kubrick, 2001

3. Vidor, The Big Parade

4. Visconti, Ossessione

[…]

[The list continues up to number 228, where SS abandons it.]

A self-described architectural writer: linear, outlined, sparse. Her “Notes on ‘Camp’” labeled it, while her emphatic review of culture—situating the high with low—provided a breath of fresh air:

The point is that there are new standards […] The new sensibility is defiantly pluralistic; […] the beauty of a machine or of the solution to a mathematical problem, of a painting by Jasper Johns, of a film by Jean-Luc Godard, and of the personalities and music of the Beatles is equally accessible.

“One culture and the new sensibility”

Her shorthand (the book is rife with bracketed names and initials, to explain Jap as Jasper John for example; one wonders if there is any New York artist or intellectual with whom she did not convene) mimics the annotation we now frequently give one another, as though everything were an aside; it is one of the most endearing aspects of the text, providing something of a familiarity to her sometimes elusive quips.

11/20/65

This is what I meant when I said Thursday evening to that offensive twerp who came up after that panel at MOMA [the Museum of Modern Art] to complain about my attack on [the American playwright Edward] Albee: “I don’t claim my opinions are right,” or “just because I have opinions doesn’t mean I’m right.”

This same friend of mine, to whom I promised a cursory overview of ’90s hip-hop no less than two years ago, came recently to collect his due. We both grew up in the Bay Area, and I can’t reasonably assert that I don’t often flick my Spotify account that way, rendering my own cultural enjoyments wide, and my sense of obligation to share them whole. Through technologies as accessible—and prized—as file sharing, Twitter accounts and iMessage access, Sontag’s journals seem arcane: the relic of a tried method of youthful introspection carried to adulthood.

I don’t know that Ms. Sontag saw culture as a YouTube channel, or how the trigger-happy touch-screen would fit with her trip to Hanoi (imagine: “Notes on ‘Pinterest’”!). But I do know that she was, ultimately, a revisionist, commenting on her own analysis of photography:

In the first of six essays in On Photography (1977), I argued that while an event known through photographs certainly becomes more real than it would have been had one never seen the photographs, after repeated exposure it also becomes less real. […] I’m not so sure now. […] To speak of reality becoming spectacle is a breathtaking provincialism. […] It assumes that everyone is a spectator. […] There are hundreds of millions of television watchers who are far from inured to what they see on television. They do not have the luxury of patronizing reality.

Regarding the Pain of Others

In that spirit, let us allow that her sentiments were not always well received as only a manifestation of the type she was, at last: fearless in some great public sense, and wantonly anxious in her private life–harsh in her personal assessments. I wonder if her persona will outlive her actual work in years to come and she will remain, ominously, only as the “Dark Lady” of American intellectualism. I, however, wouldn’t mind a lifetime anywhere with the books on these lists (her movies can be granted to another circle). But, not being burdened with a hell-subscribing faith myself, it isn’t an event I anticipate with any great haste.

—

*Italics in brackets denote editorial comments in the book.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + and our Tumblr.