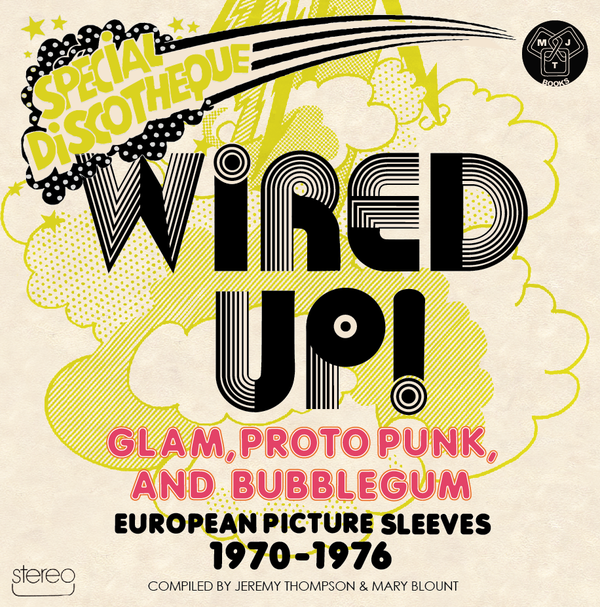

Wired Up!: Glam, Proto Punk, and Bubblegum; European Picture Sleeves 1970–1976

by Jeremy Thompson and Mary Blount

Like any other kind of history, cultural history tends to be written by the winners—or whatever group happens to have the best access to printing presses, television and radio networks, and the more influential websites and blogs. In the case of the 1970s, the “official” history of popular culture is pretty much etched in stone at this point. For pop music, the standard timeline goes something like: Beatles→AOR (“album-oriented rock”)→rich, boring, coke-snorting hippies→overblown stadium rock→the twin People’s Revolutions of punk and disco. However close to reality that progression may be (and it’s not wildly inaccurate), it omits many subgenres, fringe artists, and short-lived, oddball movements that were culturally important but tend to muddy up an otherwise tidy narrative. Jeremy Thompson and Mary Blount’s Wired Up! attempts to plug one of those holes, the youth-centered pop-music thread that moves roughly from bubble gum through flashier glitter- or glam-rock to harder-edged proto-punk. The divisions, by year or by sound, between those three styles are by no means always clear, and Thompson and Blount make no attempt to split hairs by micro-categorizing the dozens of musical artists and groups that this alternative history encompasses. What Wired Up! does is present the editors’ story chronologically, and graphically, by way of the decorative sleeves of more than three hundred 7” records of the time. This allows them to present, literally, a picture of how this music “looked” and how that look changed between the years 1970 and 1976. The result is a richly illustrated, colorful, and almost wordless book that, as a side-effect, also flaunts the massive size of this parallel pop universe, which to a surprising degree consisted of artists that are unknown today, such as Punchin’ Judy, Union Joke, Floating Opera, and the Panics. (Among the handful of better-known ones are the New York Dolls, the Sweet, Slade, the Osmonds, Suzi Quatro, the Bay City Rollers, and Sparks.) The few texts that are included are crucial; these consist of a preface, by Robin Wills of the Barracudas, that outlines the book’s proudly revisionist view of the decade, and interviews with several representative artists of the period, including members of (among others) Iron Virgin, Hector, the Jook, and the Hammersmith Gorrillas.

The sleeves included in Wired Up! are all European—with, surprisingly, an almost exclusive concentration on the continent (France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, Italy) rather than the UK—and are split into chronological sections: 1970–1971; 1972; 1973; 1974; and 1975–1976. The fact that every sleeve in the book is from a 7” single rather than an LP is itself significant, and intentional. The story of this fun, brash, youth-targeted music really does revolve around the three-minute single, and that in itself separates it from the album-oriented music that generally dominates the official history of this period. The focus on singles also happens to provide a foreshadowing of the major pop-music movements that immediately followed—punk and disco—both of which were largely singles-oriented, at least initially. (It is also notable that, according to the interviews in Wired Up!, many of the artists featured here never got around to recording full albums at all, either because their record labels didn’t have enough confidence in them to shell out that kind of money, or because the labels simply went bust too soon.)

While naturally there isn’t an absolutely clear-cut progression in the art of these sleeves over the years, certain vague trends occasionally become apparent as the years go by. The artwork on the earliest sleeves in the series is fairly primitive, even childlike: bright or garish colors, amateurish hand-lettering, and freehand drawing, much of it unabashedly cartoon-y. By 1976 the sleeve designs are getting closer to what we’d now consider “traditional” (if dated) record covers: more-formal band poses, more professionally executed lettering and art. It almost seems as if the look of the sleeves (along with the music inside?) is growing up with its audience—aimed largely at teeny-boppers in 1970, and at somewhat more adult listeners by 1976, with a more flash style in the middle. Still, in keeping with the spirit of this less “serious,” more unapologetically rocking, and primarily singles-oriented music, almost none of the art approaches the high professionalism being employed on the album covers of major AOR artists in the mid-‘70s. It’s interesting to note that the sleeve art in this book is contemporaneous with the work of, for example, Hipgnosis, the outfit responsible for such ultra-sophisticated and painstakingly rendered sleeves as Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy and Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here. Similarly, just a few short years later we would see the rise of formally trained, meticulously precise art directors like Peter Saville (Factory Records) as album-cover designers. There’s not the remotest hint of this coming paradigm-shift in the completely un-self-conscious, relentlessly Pop work represented in Wired Up!

The seven artist interviews in Wired Up! provide valuable background on this now largely forgotten world. We learn how these bands, very few of which (let’s be honest) were million-selling acts, soldiered on in the face of tepid support and seemingly countless broken promises from their labels. For example, Gordon Nicol of Iron Virgin describes how, after Decca reneged on their word to get the group the American football uniforms they’d requested for their live performances, “although we had never seen a football outfit other than on TV, we managed to make them ourselves.” (Judging from the 1973 publicity shot of the band in Wired Up! they did an amazingly good job of it.) Former glam heartthrob Brett Smiley, whose 1974 LP was shelved indefinitely and wouldn’t see the light of day until thirty years later (!), vividly recalls the battling egos and infighting that came with a promising rock career in the ‘70s, and the less-than-considerate way he was treated by the business when he was still practically a kid: “They’re basically gangsters if you ask me.” We also hear how—at least according to the Jook’s drummer, Chris Townson—the Bay City Rollers shamelessly stole their look from his band soon after seeing them perform in Scotland and telling them how much they liked their image. Subsequently, “it was bloody irritating when you go somewhere and they say, ‘You look like the Bay City Rollers.’ I think I came close to punching many people.” We also hear tales of comradely kindnesses extended to these groups by far bigger and more successful ones, as well as the occasional brush with mega-fame. Glitter-rock singer/showman Ramma Damma, to cite one example, worked with producer Giorgio Moroder for a few years until Moroder suddenly “fled to the States with Donna Summer.” The rest is disco history.

But intriguing oral histories notwithstanding, Wired Up! is all about the 7” sleeves that fill most of its nearly four hundred pages. Reproduced at full size and in glorious glam color, these are windows into a world that, while its influence on modern pop and rock music is undeniable, is today mostly unknown even to many aficionados old enough to have been there. Brought together in one place, they go a long way toward documenting an extended episode in pop-culture history that until now has been almost completely expunged from the record.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + and our Tumblr.

2 comments

Silverhead was definitely one of the groups who’s ”

influence on modern pop and rock music is undeniable”. Good to know their included here.