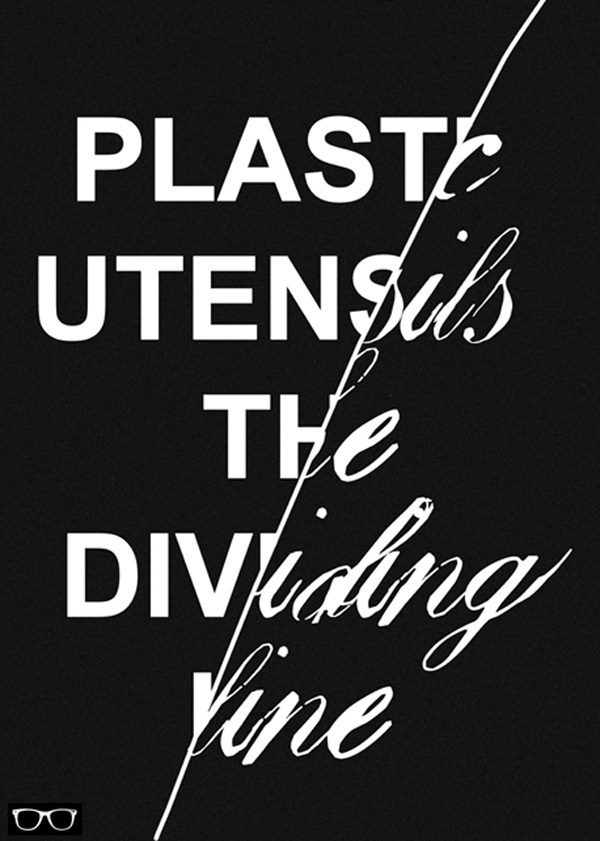

Plastic Utensils: The Dividing Line

by Andria Alefhi

I am eating my lunch, my free lunch that cost the seniors two dollars, with plastic utensils. I wonder at the nurse slicing the roast chicken breast on the bone so expertly with plastic fork and knife. She has to — it is her job to feed the elderly woman holding the baby doll, whose mind and motor skills must be gone. I push my plate away instinctually. A lunch carved with plastic fork and knife was dispensable. That’s when I think about need.

At the senior center you stand in a long line to get your meal. Some of the folks there have come just for the meal. You know because they get their tickets an hour before lunch and just sit and wait. Some all alone but others are with friends. Many are there enjoying the activities. What a giant space it is, too. What has New York changed about me? Thinking in terms of real estate. I cannot turn it off. Every event challenges me to wonder how much the space costs to rent. Activities galore, this is no lifeless senior center. Exercise bikes, people playing dominoes. Organized tai chi class and bingo games. One man was even giving haircuts complete with protective gown and electric shaver!

A voyeur, enjoying myself, no one asks what I am doing there. Clearly not of the age group and not someone’s daughter. I am left alone to read and then get lunch with the deaf woman who is helping prepare and serve. The meal is free to me and is what you would expect dished out onto a cafeteria tray. The plate is thankfully ceramic, not styrofoam, but the utensils are plastic. I sip the too-sweet apple juice and pick at my slice of what I call bodega bread. Yesterday, a woman barrels over, announcing she will take whatever we don’t want — including the salt and pepper packets, butter pat, and eaten but unfinished entree. I offer my deaf friend the yogurt and fruit, realizing in a dumb flash that she will actually eat these later, that this is real food to everyone there. A guilty memory of elementary school elitism comes over me. The thrill of throwing away food, the exposed waste; you can buy something better to eat. Something your first-generation parents would never have been able to do.

Today, the woman who asked for my leftovers offered me a pair of pants. As if this was not out of the ordinary. “What size are you?” I told her a two, and she shook her head and said that was no size she ever heard. She proceeded to show me the elastic waisted, poly-cotton blend of cheap, lifeless navy blue slacks that my mother would have worn. “I can’t return them!” she scolded. “I bought them on a sale.”

She did not bother me for leftover packets of salt and pepper today but I sat and ate with my deaf friend, still donning the hairnet. Signing to her challenges me because she is truly monolingual, which means she understands ASL only in pure form, not a Creole of English-ordered grammar and modern words many interpreters expect are easily understood. I read a few business letters to her, thinking before I translate. Thinking about how closely what we can learn is limited to what we experience and know. Like love. Like humanity.

I have written about interpreting for jobs where I must interclass, and it humbles and fascinates me anew each time. She needs this training and would probably stand in line to get it. I need work. For sure, fifty other interpreters would stand in line for this eight-hour job that is mine for today. We all need the same things really, but at a certain level I guess you could say the line is more in your mind than literal. I try to look impressed with the chicken I struggle to slice with plastic. I could be eating one thousand different lunches in a hundred different spots today because I have money, a command of the language, and time. Instead, I fit conversation into bite-sized pieces in her language while she picks the bone clean.

Andria Alefhi publishes a nonfiction literary journal called We’ll Never Have Paris. Her own writing will appear in a collection of stories in February 2013 on iLOAN books.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + and our Tumblr.

1 comment

Andria has such a way with language. One sentence is laugh-out-loud funny and the next will break your heart. I look forward to reading more from her.