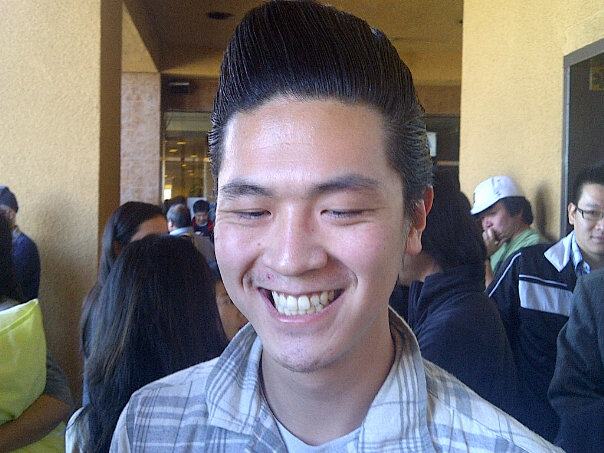

I used to have really long hair–long enough that if it had lasted until Halloween, I could’ve passed for a young James Iha of the Smashing Pumpkins. Long enough that it earned me a few cat calls from men who’d seen me from behind, regular instances of being referred to as “Miss.” I’d always wanted to wear a pompadour, and when I got tired of wrapping my head in a towel post-shower I went to Tomcat’s Barbershop in Greenpoint and left looking like a Chinese Pete Campbell from Mad Men. In that first month of greasing and combing my hair, I was newly self-conscious about the form, shape, and execution of my new hairstyle. I thought, do all guys spend this much time thinking about their hair? I noticed that even three hairs out of place, or a split right in the middle of the forehead, totally made me look unbalanced. To what extent was I performing an ideal perception of myself? What was I comparing my pompadour against? This last question spawned an obsessive curiosity into the origins of the pompadour, arguably the epitome of classic mid-century American hair. What I found was a total surprise, and not only in terms of its history and evolution, but in my initial perception of its gender.

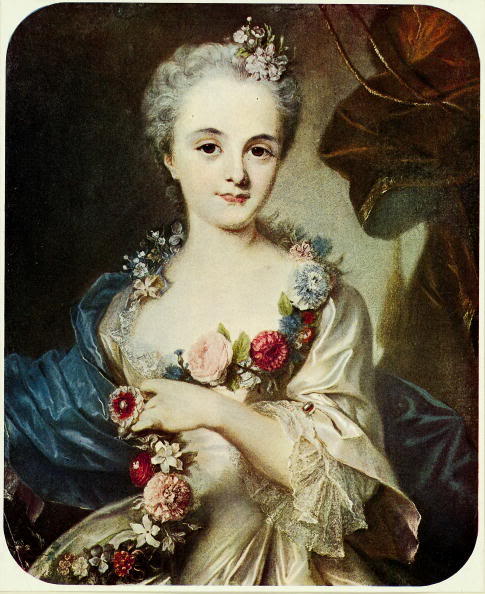

The pompadour is a 300 year old hairstyle, incepted by one Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, the Madame de Pompadour. “Pompadour” is the shortened form of Arnac-Pompadour, a commune in the Corrèze area of central France, and how the name of a region becomes a hairstyle is interesting: Poisson wasn’t born into French aristocracy–her family came from middle-class means (and purportedly a father who had to skip town because of his outstanding debts), and she was educated first at a convent then under the tutelage of her mother. She learned to paint and engrave, and eventually became an accomplished actress. After she married the nephew of her legal guardian, King Louis XV heard of her after she was introduced to the royal court, and subsequently became his chief mistress. Poisson was officiated as a mistress with the new, though largely ineffectual title, Madame de Pompadour. In her role, Poisson held more sway over feminine aesthetics than national politics. As a patroness to the arts, her appearance on the public stage helped establish the trend among women copying her hairstyle: tall, voluminous coiffs were built around wire frames. These women frizzed their hair for more volume, swept it high off the face, and rolled it over a wire frame stuffed with straw or fabric. Over time, the pompadour grew in size and drama: ornamental objects were added to the style, and those who could afford it used professional hairdressers. These large, embellished pompadours were signs of wealth and status. Pomade, which was first made with bear fat, was used to set the style.

In the next century, the wire frames disappeared and were replaced with a mound of false hair or other padding called a postiche, sometimes called a “rat.” The pompadour traveled to England towards the end of the 19th-century, and was well established as an upper-class hairstyle by Alexandra of Denmark, Princess of Wales, wife of future King Edward VII. English women would wear their pompadours with an “Alexandra fringe,” hair ornaments and all. Closer to the turn of the century, the pompadour is introduced to the North American continent via the illustrations of Charles Dana Gibson, who based his “Gibson Girls” on his wife, Irene Longhorne.

The Gibson Girl is important to the history of the pompadour: it is the initial move away from the exclusive realm of the upper classes to the middle classes. Gibson girls were often depicted playing outdoors, often sans men, wearing natural-looking garments that enabled freedom of movement. These representations allowed women of all classes to adopt the pompadour, which also innovated the hairstyle: one side of the hair might be left hanging over the shoulders, or a stray curl would be left loose on purpose. The pompadour was no longer restricted to a large mound: locks would be piled over a postiche now made from the wearer’s own hair, saved from the hair brush. In 1925, personal grooming companies like Murray’s and Royal Crown began using petroleum jelly to make pomade, availing the product to the masses. Men of this era predominantly used a product called brilliantine–which produced an identical shine to pomade but was made from oil–which could evince the possibility of men thinking about wearing their own pompadours.

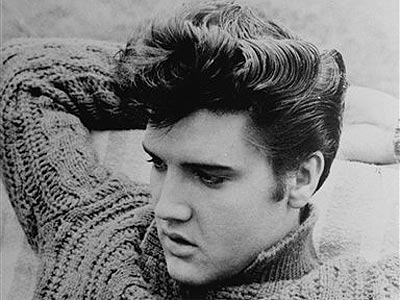

The male pompadour is characterized by slicked back sides that meet at the nape of the neck into a duck tail, or duck ass, with a small round mound resting on the forehead. In contrast to most of the cuts modern-but-old barbershops are cutting, the classic pompadour isn’t combed with a part, nor are the sides or the back of the neck faded up towards the top of the head. While it started sometime between the 1920s and the ‘50s, there’s little to no popular documentation on exactly how or why men came to wear the pompadour. For our American popular history, it’s bound up in the birth of rock’n’roll, and the breakout of Elvis Presley in 1956. Presley is the figure who allows men to comb their hair up, albeit much smaller than its original. What’s so great about Presley, the pompadour, and his popularization of rock’n’roll is the maintenance of the drama and performativity of this once aristocratic, feminine haircut: there’s plenty of documentation that The King dyed his hair black to further dramatize his public persona, to solidify the rock’n’roll personhood of shaking hips, moaning, roaring vocals, and ripfire sensuality.

By 1958, Presley is American popular culture royalty, affirming the popular American narrative of rags to riches, not unlike the Madame de Pompadour. Coming from modest origins, Presley, along with film icons Marlon Brando and James Dean, effectively made the pompadour the epitome of the new American male. There was so much admiration for Presley’s pompadour that when he was drafted into the Army, photographs of of him in the Army barber chair were printed in newspapers across the country. It was such a significant moment in popular culture that the moment was quickly mimicked in the film and stage versions of Bye-Bye Birdie. There, Presley-via-Conrad Birdie gets drafted into the army, has his picture printed in the paper of him in the Army barber chair, much to the dismay of his thousands of fans. Presley was highly self-conscious of the cult of his pompadour: upon marriage to his first wife Priscilla, mother of Lisa-Marie, he insisted that she dye her hair black to match his. Presley’s pompadour evolved throughout his career–his Vegas years saw the pompadour and mullet combined, which lives on through the careers of Elvis impersonators and Japanese rockabillies (more on them later). Presley had a personal hairdresser for over thirty years, Homer “Gill” Gilleland of Memphis, Tennessee. Gill saved clippings from Presley’s haircuts over a period of twenty years, and by the time it sold it measured three inches in diameter, and estimated to hold thousands upon thousands of hairs. It sold for $115,120 at auction. Presley also elevated the pompadour away from a strict hairstyle to a genre: because of its link with rock’n’roll, the bands that followed in his wake greased their hair into variations of the bouncy mound and introduced the waterfall, the jellyroll (more popular among British Teddy Boys than American rockers), devil-lock, and quiff as forms of the pompadour. Though largely lost in the `70s, the pompadour returned with the rockabilly comeback of the ‘80s here and across the pond, found on the heads of Brian Setzer, Billy Zoom of X, and almost every psychobilly band then and even now.

Most men’s-focused lifestyle magazines will juxtapose the resurgence of the pompadour in popular culture with one show: Mad Men. Though no one on that shows wears a pompadour, the aesthetics and costumes of that period evoke the sensuality and drama of the rockers and greasers absent on the show, funneling all of that sexual energy through Draper and Campbell and Peggy and Sterling and yes, even Lane Pryce. Combine all that with our current predilection with heritage brands, authentic vintage clothing, and the oft-mourned period of Levi’s Vintage Clothing of 1999-2006 (where 501s and other garments were on original cotton looms in the company’s original San Francisco factory at a premium price), sartorially-conscious men have brought the pompadour back to popularity. What it’s evoking is that sexuality and sensuality within a clean-yet-rugged masculinity; it’s a performed aesthetic of a mythologized American era wrapped up in “classic” ideals of American masculinity, those same ideals that have their historical origins in feminine aesthetics of 18th-Century French aristocracy. The last ten years have seen the pompadour move beyond rock’n’roll too: Justin Bieber, for instance, wears his hair in a pompadour. Many couture fashion houses wholly unconcerned with authenticity pomp their models’ hair, albeit without Murray’s Superior or Layrite.

I’d like to stress that the drama, performativity, and flamboyance of this haircut often associated with American masculinity is inextricably linked to Poisson. Along the same lines of that aristocratic culture–where women were rarely allowed to be free individuals in their social roles of wife, where they were objectified into ornamental figures both aesthetically and socially, stage partners to their husbands on the socio-political stage–was it not Elvis Presley’s new form of staged sensuality and sexuality–a far cry from male vocalists like Johnny Mathis and Bing Crosby–that shot him to fame? Relative to those crooners, was it not Presley’s flamboyance that constituted much of the popular response, men and women alike? It’s because of this that the transition from a predominantly feminine haircut becomes masculinized. That Presley spawned millions of men to start their own bands, replete with their own pompadours, means we popularly understand the pompadour as a masculine haircut.

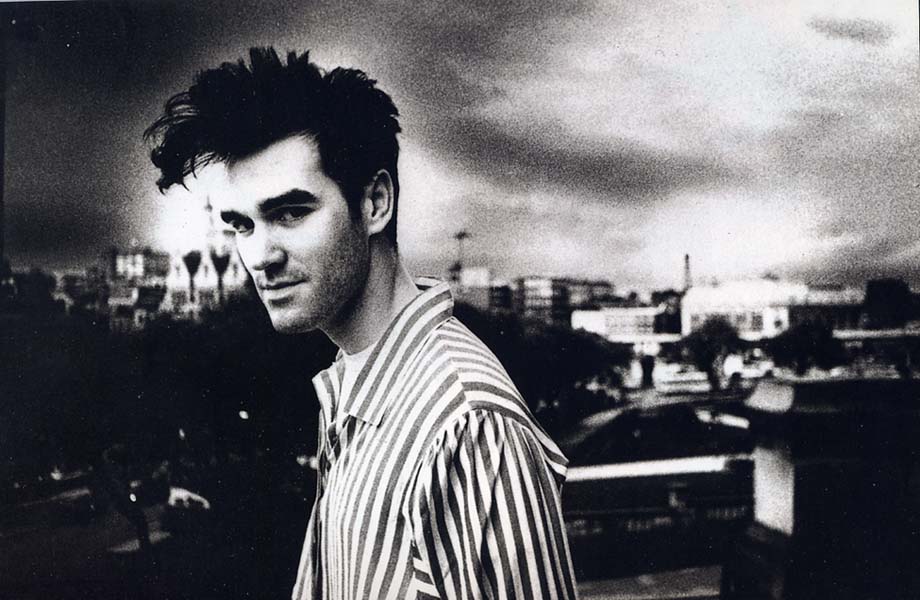

This is not to say that women stopped wearing pompadours once Presley hit the mainstream, but it was he that wrest it from its feminine origins. The female pompadour today seems more strictly associated with the contemporary rockabilly scene: Imelda May, a popular contemporary rockabilly recording artist, wears hers as a spiral bump, and much smaller than the Gibson Girl’s. Janelle Monae has a beautiful pompadour that evokes James Brown’s during the ‘60s. But still, our most immediate connection with the pompadour is less R&B and Soul than rock’n’roll. There, the popular association with Presley’s masculinity buries the feminine, aristocratic origins in favor of the working class, rocker realm; still, there are figures today that frustrate the classic masculine ideal. Morrissey’s wispy, airy quiff completes a nice dyad with his infamous refusal to “pick a side” with straight or gay; it simultaneously nods to the rock’n’roll history while arguing against all the rigid associations. I find this an extremely important political move: it’s a sign that not only are gender roles performative, but also that rigid gender roles are counter-productive, closed-minded, and restrictive.

The pompadour is sort of like a transhistorical organic garment of gender play and equality. Maybe this is why the pompadour has lasted for so long: male, anyone can wear them; it can be worn within the strict confines of masculinity and femininity or within an androgynous space. But it is all about performance, play, and sensuality. The Japanese rockabillies featured in the video for the Peter, Bjorn and John song “Nothing to Worry About” take their pompadours to an extreme or, arguably, back to basics.

In Japan, “gangs” of Japanese rockabillies outfitted in leather pants and motorcycle jackets convene in parks to dance to American rock’n’roll standards, actively participating in the breathing myth of classic Americana strictly through the staged performance of that time, just as our current trend pays homage to that era. It’s all a performance and performative of fun, loosey-goosey free-spiritedness, a statement of one’s personal perception of status and sensuality. As much as our ideals of masculinity do not often include significant time and attention paid to grooming, let’s not forget that Presley had a personal hairdresser, that he wanted–chose–and appreciated a flamboyant personality. It’s just as important for the masculine ideal to be frustrated from within as much as its still vital for our ideals of femininity to be reconstituted outside of the male gaze. Our personal aesthetics can be socio-political statements, and often are, so let’s not forget the pompadour is centuries old, has its roots in drama and performance and gender play. Sorry to say to some of you who are feeling extremely masculine after getting your hair pomped: you’re playing with gender roles. It’s OK: let’s just move on, have fun, and cut Justin Bieber’s hair off.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

2 comments

I am doing a research on this and yours was very helpful. Thanks.

Rock it!! And I agree, lets not freak out and just move onto cutting Justin Beibers head er HAIR off!!