When I spoke with Jesse Lortz in 2011, he noted that he was “currently working on a book of short stories and poems. I will be self publishing it and trying to sell it in book or magazine shops!” Lortz was one of two singer/guitarists in The Dutchess and the Duke; since that group’s dissolution, he has continued making music under the name Case Studies, releasing the stark The World Is Just a Shape to Fill the Night later that year.

When I spoke with Jesse Lortz in 2011, he noted that he was “currently working on a book of short stories and poems. I will be self publishing it and trying to sell it in book or magazine shops!” Lortz was one of two singer/guitarists in The Dutchess and the Duke; since that group’s dissolution, he has continued making music under the name Case Studies, releasing the stark The World Is Just a Shape to Fill the Night later that year.

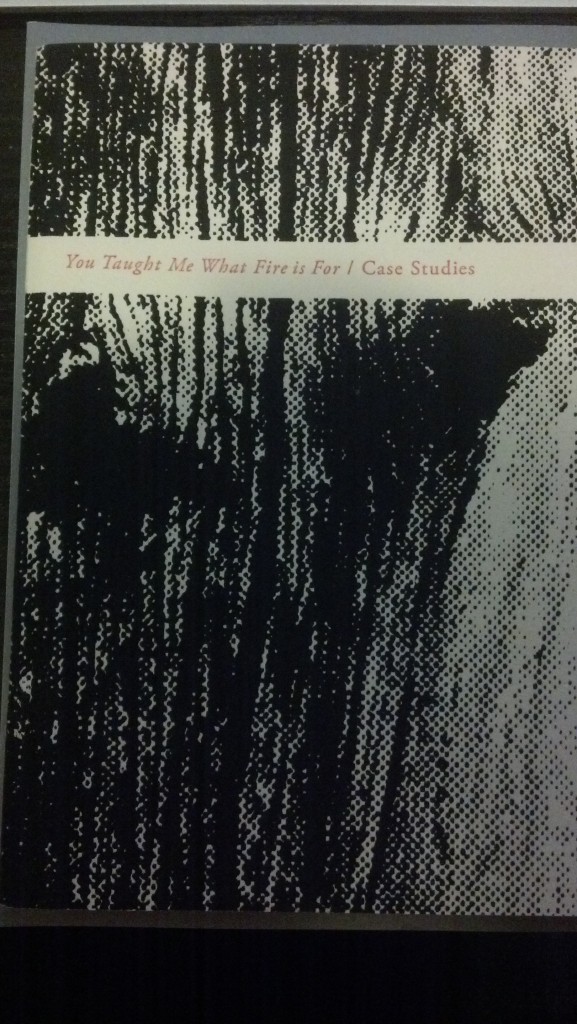

He wasn’t kidding about the book component of Case Studies, either. You Taught Me What Fire is For, released by Morgen Mond, collects Lortz’ lyrics in a concise, nicely-assembled package. Those familiar with his music won’t be surprised to learn that these lyrics abound with visceral and often symbolic imagery. Lives collide, and some pieces are told from the perspective of a participant staggering from the wreckage.

There are ghost stories Californian and Texan both to be found here; it’s all collected in a neatly bound chapbook, the clarity of its arrangement belying the raw emotions conveyed within. “These are the songs that have left so many ashes and these songs are the glowing coals of things to come,” writes Lortz in an introduction; with Case Studies working on new recordings, I’m eager to hear what those coals produce — and what other art they might beget.

Like Lortz, Donivan Berube is a talented singer/songwriter whose artistic scope extends beyond music and lyrics. He’s part of the group Blessed Feathers (who I interviewed in October), and also edits a zine called Sleeping in a Torn Quilt / Dreaming of Gold.

Collected here are contributions from musicians, including Berube and his bandmate in Blessed Feathers, Jacquelyn Beaupre. The zine itself is assembled on dense multicolored paper, which gives it a sturdy feel; one downside of this approach, though, is that certain colors don’t lend themselves all that well to text. (Reading black type on a red background wasn’t the most pleasant experience of my reading life.)

Highlights of this issue include Swans/Shearwater drummer Thor Harris’s surreal, creepy illustration; an essay from Berube on Maurice Sendak and mortality; and short prose pieces from James Andre and Colin Caulfield. When I interviewed Berube about how he’d come to work with some of these artists, he noted that, “[m]ost of them, the musicians particularly, probably wouldn’t tag themselves as ‘writers.’ I’m not too comfortable with that either. But I contact and work with them individually based upon what I discern them to be into or capable of.” And both of these publications find a way to extend a particular aesthetic into realms beyond music.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.