The first time I read David Foster Wallace, I didn’t realize that I was reading David Foster Wallace. It took me until I read A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again — which I came to relatively late in my Wallace-reading — to realize just when it was that I’d first encountered an example of Wallace’s writing. It wasn’t in that collection, nor was it in his Atlantic piece on talk radio, my first encounter with his writing in a magazine where I recognized it as such; nor was it in Consider the Lobster, the first actual book of his work that I purchased.

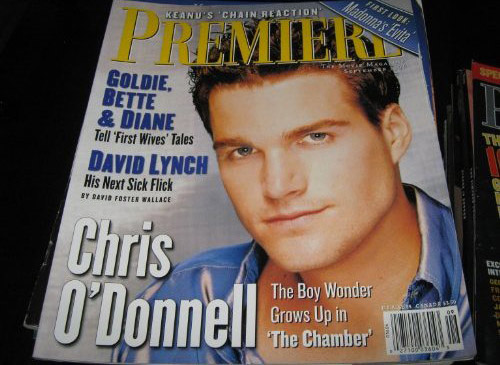

My first encounter with the writing of David Foster Wallace came in the pages of Premiere magazine, in an article where he examined the work of David Lynch, specifically as it related to Lynch’s then-new film Lost Highway. “David Lynch Keeps His Head,” the article was called. Looking back at it now, I see that it appeared in the September 1996 issue of Premiere — so I either would have been newly arrived at NYU for my sophomore year there or would have been lurking around central New Jersey, going to hardcore shows in VFW hall basements and driving north and south on Route 18. At the time, I was soaking up as much writing on film as I possibly could; somewhere in New Jersey, there’s a large Tupperware container full of old issues of Premiere, Movieline, and Film Threat.

Over a decade later, I would encounter “David Lynch Keeps His Head” again, within the pages of A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again. It’s very likely that I made some sort of affirmative grunting sound: a “huh” or “hmm.” Maybe even an exclamatory, “Hey!” At the time that I first read “David Lynch Keeps His Head,” I hadn’t known who David Foster Wallace was. If pressed, the 1996 version of me would probably have recognized the title of the story collection Girl With Curious Hair — or even the just-released Infinite Jest — from seeing them on tables in the front of bookstores. Most of my reading at the time was science fiction, along with, well, magazines about the film industry.

I can’t say that “David Lynch Keeps His Head” rewrote how I interacted with nonfiction. It was a memorable enough piece of writing that I remembered it ten years later: of course David Foster Wallace wrote that. The fragmentary style, fixations on Lynch’s own demolitions of narrative, and focus on unexpected minutiae. Essentially, it’s a writer with no interest in most aspects of celebrity journalism profiling a director with a similar attitude. And as such, it was memorable: its approach ran counter to the profiles I was used to reading. Looking back on “David Lynch Keeps His Head” now, the ways in which it collapses expected structures still feel immediately striking.

***

To leap back a moment to that sensation of recognition, of unexpected remembrance: David Foster Wallace was not the only writer for whom I’ve felt this kind of jarring yet not unpleasant emotion. It also came up when reading the case studies contained within William T. Vollmann’s exploration of violence, Rising Up and Rising Down, as well as Dennis Cooper’s recent nonfiction collection Smothered in Hugs. In each case, there was a pause as my brain found certain words familiar, recollected what had by then become a familiar authorial point of view. In the case of Cooper, it was a profile of Courtney Love, abounding with irreverent humor and an offbeat approach towards its subject. I had a long way from my first encounter with Cooper to reaching a more familiar place with respect to his work: Of course this is piece is written this way; it’s by Dennis Cooper. It’s possible that I was more aware of Vollmann’s persona when I was a high school reader of SPIN. His dispatches from war in the former Yugoslavia were utterly gripping at the time. Was I aware of them when I first walked to — if memory serves — St. Mark’s Books in 1999 or 2000 and pulled The Atlas down from the shelf? That I don’t know.

I’ve been thinking about that a lot as I’ve been considering this piece. David Foster Wallace, William T. Vollmann, and Dennis Cooper all fell — and continue to fall — onto the more experimental side of the fictional spectrum. And yet all three wrote for publications with a relatively wide audience. This isn’t analogous to a writer penning a book review for the New York TImes or Bookforum; instead, this was a way in which a kid living in the suburbs could potentially have their first experience with weird art.

It begs the question: two decades since those pieces first ran, are there analogous writer-publication pairings? Might someone discover a window to the shores of the avant-garde while reading an interview with their favorite actor, director, or musician?

I’m tempted to answer that with an emphatic “maybe.” Clearly, the landscape of magazines focusing on culture looks different today than it did in the mid-90s. Still: Roxane Gay has been writing regularly about all things cultural for Salon.com; Blake Butler has deftly covered music for the likes of Vice and The Oxford American; Rookie has hosted work from numerous literary types; and Vanessa Veselka has followed her dazzling novel Zazen with nonfiction for GQ. Michael Robbins earned rave reviews for his poetry collection Alien Vs. Predator, but seemed equally at home writing about My Bloody Valentine’s new album for SPIN.

Stephen Elliott and Geoff Dyer also come to mind, but for both, their fiction and nonfiction seem like equally valid aspects of a carefully constructed persona — one that blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction. Which isn’t to say that David Foster Wallace, Dennis Cooper, and William T. Vollmann don’t posess iconic personae as well — but the cultivation of that seems simutaneously easier and more fraught in this day and age. Outlets for large-scale culture writing are evolving or (in some cases) vanishing; sites like The Rumpus and Thought Catalog have made essays more visible (and viable). And at times, I get the sense that there’s an increasing specialization: between music writers and fiction writers and film writers and essayists. All of which won’t prevent the contemporary version of me-at-16 from finding the contemporary equivalent of “David Lynch Keeps His Head.” What its contemporary equivalent might be, I can’t say for sure — but I hope that iconic writers never stop seeking out artists who they consider, in Wallace’s words, “grandly admirable and sort of nuts,” and in doing so, ably lead us to their own admirable work.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

2 comments

Dear Tobias,

Great read! You go from capturing your life as a young reader–there’s that enjoyable luck of stumbling upon writers you’ll later learn are such big names. Then you go into questions about the nonfiction-for-a-mass-audience/experimental-ish-fiction happening today. Fantastic. Best, –Alex K.