And sometimes, you want a scary story — or close to a dozen of them. The three books discussed here today — Yoko Ogawa’s Revenge: Eleven Dark Tales, Adrian Van Young’s The Man Who Noticed Everything, and Manuel Gonzales’s The Miniature Wife and Other Stories — balance literary craftsmanship with a knack for the uncanny. Whether evoking quotidian rhythms only to replace them with something more sinister or shifting tales of upset lives into something more structurally ambitious, these books unnerve even as they intrigue.

Adrian Van Young’s debut collection, The Man Who Noticed Everything, sits neatly between Donald Ray Pollock’s rust-stained noir and Brian Evenson’s more surreal tales of existential horror and bloodletting. The title story focuses on a drifter hired for a particularly unpleasant task in upstate New York; he’s still reeling from a violent act he can’t remember and a past that remains unknown to him. There’s a repeated action, a sort of romance; a sinister house on a hill, a repeated dream. There’s violence, some of it in the past and some of it yet to come. It’s a gripping narrative in its own right, with just enough surrealism added to heighten its inherent unpredictability. Elsewhere in the book, solitude is disrupted by intrusions human and otherwise; subletters drive their hosts to madness; and the legacy of the Civil War shatters families across decades. It’s a potent and considered collection.

At first, I thought I had Yoko Ogawa’s Revenge pegged. Here was a series of stories, each loosely related; the protagonist of one could show up in the background of another, or be the cause of another character’s misery. Throughout the book, I encountered characters reeling from trauma (and, in some cases, inflicting it.) The multifaceted approach led to some interesting shifts: the mysterious caretaker in “Welcome to the Museum of Torture” is revealed to have a much less dramatic background in a subsequent story, for instance. But the presence of a paranoid, possibly delusional writer in here leads the book to an unexpected place, structurally speaking; rather than a neat cycle, Ogawa pushes the collected narrative towards a fragmented conclusion, accentuating the book’s most unsettling aspects.

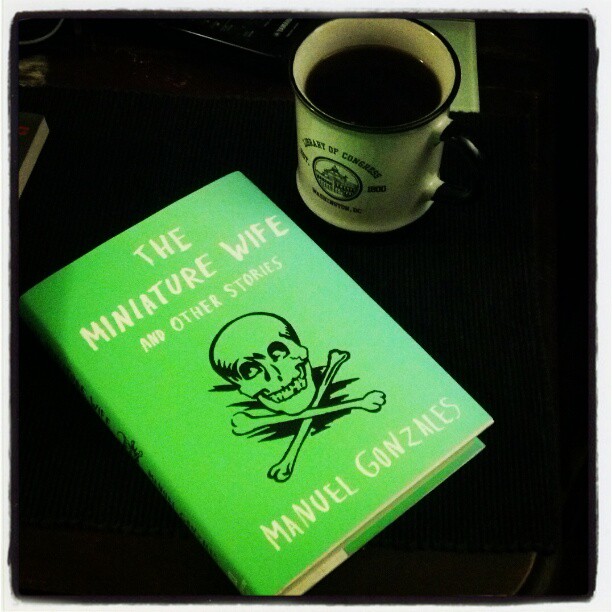

Manuel Gonzeles’s The Miniature Wife is at its strongest when evoking a sort of horrific dream logic. Both “The Animal House” and “Pilot, Copilot, Writer” feature doses of the inexplicable: in the former, it’s in the unexplained migration of most of the population of a small town; in the latter, it’s in the seemingly endless flight of a hijacked airplane, going on twenty years as the story opens. These stories in particular tap into certain anxieties, and though they may be irrational, they lend these narratives a consistent underlying logic. The collection is punctuated by short accounts of strangely distinctive lives, and Gonzeles excels in writing about the absurd in a straightlaced manner. It’s a strength also demonstrated in “The Disappearance of the Sebali Tribe,” about an anthropological expedition that may not be what it seems. Certain parts of the collection revisit familiar terrain — zombies, werewolves — with less distinctive results. But his evocation of various cities and towns in Texas impresses as much as his command of the fantastic, and the vast majority of these works elicit both wonder and dread.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

1 comment