Our Love Will Go the Way of the Salmon

by Cameron Pierce

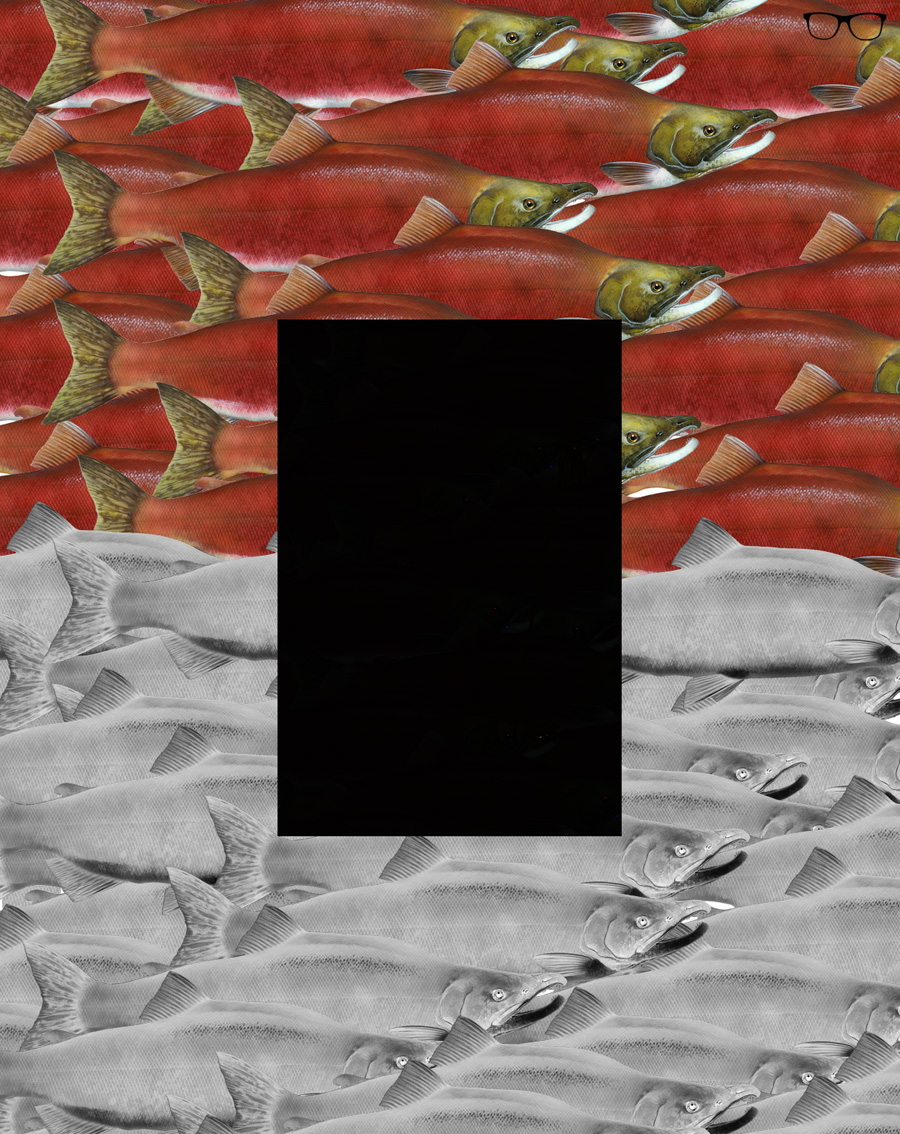

The ducks in the lake were mechanical, but after all these years, all these disasters, the salmon remained flesh and blood. They carried battle scars. They hung out in the shade of overhanging trees and beneath the decaying dock, sighing once in a while in remembrance of all they’d gone through. Not to mention the fellow salmon lost along the way.

The salmon had officially retired about a decade before. I moved out of Oregon around the same time. I figured if I could no longer catch salmon in the lake where my grandmother had taught me to catch them, what was the point of living in a place. I returned because Grandma rang me up a few nights back and she said, “Greg, take me fishing one last time.” So I called in several sick days at the mill and packed my bags.

As we stood there on the shore of Mt. Hood Lake, listening to the ducks quack robotic, I came face to face with the small distance we had traveled in our lives since the days when this lake greeted us like a cathedral made of fins and scales. Grandma could no longer walk. I had to push her in a rickety wooden wheelchair that she complained gave her splinters. As for myself, I was turning forty soon, pushing fifty in the face and two-hundred on the scale. She was twice divorced. I was never married.

I figured she wouldn’t much notice the difference between our old salmon rods – nine-foot sabers with a whole lot of backbone and acrobatic tips – and the ultra-light Eagle Claw trout rods we were using today. What I didn’t anticipate was for Grandma to be mostly blind. She never mentioned it when we talked on the phone, but when I watched her, I just knew.

As I baited her up with some chartreuse Power Bait, she asked me, “So Greg, are we fishing herring plugs or spin-n-glos today?”

“Herring,” I lied.

If she knew I was lying, she didn’t let on. I handed her the rod and stepped back about ten yards before her first cast. With her vision gone, I figured there’d be a good chance her bait-covered hook would end up in a tree. Or worse, in my skull. But Grandma cast out perfectly. The bait chased the aluminum split shots down into the lake. And before I could even cast my own line out, she had a fish on.

“Come on out, you bastard!” she shouted, muscling a trout toward the shore with her frail ninety-year-old arms. That was Grandma. Crippled and blind, but totally mad for fish. My very own Captain Ahab.

The trout leaped out of the water and then dove down deep, making one last desperate dash for freedom, but Grandma kept the line taught. Soon, the trout flailed amongst the weeds that lined the shore. Grandma lifted the fish into her lap. It was a one pound stocker trout, nothing like the twenty pound silvers we used to pull out of there. The trout’s rainbow stripes reflected in her dark and shiny eyes, but there was no way to tell whether she knew she’d caught a trout. Maybe she just thought it was a dinky jack.

The fish flopped out of her lap and into the dirt. “Better bonk ’em, Greg,” she said. “This here’s a firecracker.”

I nodded as I fetched a pair of needle-nose pliers, the mallet used to conk fish, and a nylon stringer.

I unhooked the trout and held its body in a firm grip. I lowered the fish to the ground, my hand pinning its soft body against a flat rock.

The mallet came down too far up the fish’s skull and its eye popped out. Flecks of blood confettied my glasses.

I hammered down again, on target this time.

The fish stopped moving.

The errant eye lay on a rock. The dilated shock-gaze of being captured, of choking on oxygen, remained. A pool of black ringed by gold.

I flicked the eye into the lake.

With the dirty work out of the way, I baited Grandma up again and then finally prepared to cast out myself. I’d hardly flipped the reel’s bail when once again Grandma was rearing back on her rod.

“Fish on! Fish on!” The line unspooled from her reel like it’d gotten snagged around a Boeing 747 on a hasty flight heading for Japan. “It’s a big one, Greg!”

The biggest trout ever taken out of Mt. Hood Lake couldn’t have pushed seven pounds. I wondered if Grandma might break that record now, but I also worried that the yellowed, frayed line on her pole might not stand up to a bigger fish. I’d been in too much of a hurry to hit the road and had failed to prepare the way I usually do. So now because of me, Grandma was going to lose her big fish.

I cranked in my line to keep it out of her way.

Her wheelchair lurched toward the waterline. The wheels sank into the mud.

The rod buckled in a horseshoe and she flexed her arms in spindly right angles, fighting to keep the rod tip up.

The scream of the line whirring off her reel could have set a forest ablaze.

And her wheelchair inched ever closer to the lapping water.

“Hold me back, Greg. It’s pulling me in.”

“Loosen the drag,” I said, licking sweat off my sandpaper upper lip. “Let the fish run.”

“Please, it’s pulling me in!”

Like a ventriloquist, I raised my arms and lowered my red-gloved hands onto the back of her splintered chair. Squeezed.

I held on.

My hands went numb. My boots sank into the mud.

Finally, she loosened the drag and the line unspooled ever-faster as the first raindrops pelted the water. At least, while the drag was loose, we could breathe, relieved of the threat of being pulled under.

The rain blew in slants that whipped our faces. I squinted out to where the fish was running, a tree-studded outlet where it could wrap around an underwater stump and snap the line.

A mechanical duck swam along the weed line in front of us and pecked at the floating eye. The duck gulped down the eye and floated on.

“Shit, she’s gonna strip me,” Grandma said. The tips of her fingers had been sliced. I’d been right. She was blind as shit. The only way she could keep track of how much line she had out was to keep her fingertips on it.

Sure enough, a mere thirty yards of yellowed, frayed line remained on her bail. I looked to where her line ran into the water. Her line was now a bloody red wire cutting through the gray-green of the water.

If we failed to act now, the fish was gone.

She tightened the drag to where the fish could no longer draw off more without exerting itself. I anchored my boots deeper in the mud, crouched over with my arms looped through the arms of Grandma’s wheelchair, ready for the fight to come.

“You may break me off or spit me out, but no son of a bitch strips me clean,” Grandma said to the fish.

She made one counterclockwise reel and waited to see what the fish would do.

Grandma’s musty rose perfume was made harsher by the rain. I tried to raise a hand to my nose to block a sneeze, but my arms were locked in her wheelchair. The sneeze was coming. No stopping it. I tucked my head in like a turtle and sneezed into the wheelchair’s slatted backing. Grandma craned her neck. A mean scowl crossed her face.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“Not as sorry as I,” she whispered.

I had no idea what she was sorry about, but before I could ask, all the tension vanished from her line.

“Hold on tight,” she said, beginning to crank the reel. “Big mama might decide to run.”

She licked the rain from her gray lips. Narrowed her clouded eyes in concentration. Cranked in more line.

The fish had given up, but the fight wasn’t over. The fish might recover. The hook might come loose. The line might get wrapped around submerged debris. Anything was possible in a fight with a lunker.

I hunkered down with my boots and butt in the mud, arms locked in the wheelchair’s arms. Even with the fish conceding like this, my anchoring weight was the only thing keeping Grandma ashore. The beast was that big.

She brought the fish in one crank at a time. The going was persistent but slow. The rain lessened and I took that as a good sign. My lower body was numb.

Finally, the fish surfaced. Twenty yards out, it burst out of the water and soared in a glorious arc like a dolphin.

“Grandma, do you see it?” I shouted. And then I wept because I knew she could not see the fish, and because the fish was so great.

She did not answer me, but there were tears in her eyes too.

A salmon had come out of retirement to do battle with Grandma. Not just any salmon, either. This was the queen mother of Mt. Hood Lake. An ancient, five foot long, razor-toothed beauty. Only a true fisherman like Grandma could have fought such a fish on an ultra-light rod. The catch would be made even more glorious and bizarre, for it would be made on Power Bait, that foul-smelling artificial trout attractant that had never, in the history of fishing, yielded a salmon except in the lore of liars.

“Grandma, when you get the fish in closer, I’m gonna wade out and wrangle it ashore.”

“Don’t let go of me,” she said. “It’s too big.”

“I won’t let you go,” I told her, and I squeezed her wheelchair closer to me, just so she’d know.

But when the fish thrashed only a few yards out, I freed my arms from the wheelchair and lurched out of the mud. I sprang up and dashed through the weed layer and into the frigid water. Grandma shouted for me, but I was locked on the silver chaos.

In hip-deep water, I came to stand beside the salmon. I reached my arms around it but the fish knocked me backward with its powerful tail.

My head dipped and when I came up, my glasses were gone. I found my footing on the sandy bottom and looked all around. Grandma was shouting. Her wheelchair was empty in the weeds at the water’s edge. She’d been pulled out. She was a blur in the shallows, a broken lightning bolt in her hands.

I rushed for the salmon, pounced upon it. I got a grip on its lower jaw. Its teeth tore my calloused hands, but I took a deep breath and held on as we went under.

The fish thrashed against me, a thing of force and muscle. We rolled underwater as one.

I dug my fingers deep into its flesh and felt my other hand along its body to its gills, intending to rip them out.

I stabbed my hand beneath the gill plate like a knife, but the fish bucked away and suddenly was gone. I could hold my breath no longer, and surfaced.

Grandma was gone.

I dove under again, but in the gray-green I saw nothing. I called out. I waited. Eventually, I backed out of the lake, collapsing in the shallows, shivering.

My soaked clothes clung.

I crawled through the mud and heaved my body onto her overturned wheelchair in the weeds.

Cameron Pierce is the head editor of Lazy Fascist Press and Wonderland Book Award-winning author of eight books, most recently Die You Doughnut Bastards (Eraserhead Press, 2012). He lives with his wife in Portland, Oregon.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

3 comments

followed every sentence until the bittersweet end.

a new direction for Pierce–a bit more Hemingway-esque, but still containing his dark/tragic sense of whimsy. His story “Lantern Jaws” has recently become one of my favorite shorts of all time.