In writing about the art of sport, and the potential poetics of these games, there is a temptation to chase secret mechanics in the language of memoirs, biographies, histories, and the like. I’m always looking for a captivating, well-written book that will offer insights not merely into the experiences of athletes – teamwork, practice, composure – but the hard data of the game. How to Throw a Curveball, How to Rebound, How to Render an Opponent Unconscious. This pursuit is challenging, for the same reason that it’s rare to find great prose from physicists or porn stars: raw scientific process is difficult to capture in romantic phrasing.

The qualities which Vince Lombardi held as paramount — “perseverance, self-denial, hard work, sacrifice, dedication and respect for authority” — are the sorts of qualities which most writers could use more of, and most athletes-aspiring-to-write could stand to forget. Sports memoirs are no doubt written quickly and efficiently: one can easily picture Wayne Gretzky or Joe Montana having no problem waking up early and banging out pages with the tenacity of an Updike or Stephen King. But Lombardi’s virtue of self-denial cuts to the core. While great writers tend to be industrious and able to make basic sacrifices, they are likely to be introspective to the point of self-absorption, if not downright narcissism.

Still, I don’t wish to create an oversimplified false choice between the mechanical excellence-by-repetition nature of Romantic with a Capital R. The middle ground between practical knowledge and great writing usually comes in the conduit of a journalist. The Great Santini author Pat Conroy was the captain of his college basketball team, the Citadel Bulldogs, and wrote an entertaining book about it, My Losing Season. Another way into a great book on playing sports is to be a great writer first. George Plimpton’s Paper Lion, in which a man who could have been the perennial centerfold in Frail Dandy Monthly enters the Detroit Lions training camp (as a quarterback, no less) is if nothing else, an interesting and often LOL-worthy experiment. The best fictionalized depiction of sport in recent memory comes in one of the more direct commentaries within Chad Harbach’s The Art of Fielding:

“For Schwartz this formed the paradox at the heart of baseball, or football, or any other sport. You loved it because you considered it an art: an apparently pointless affair, undertaken by people with special aptitude, which sidestepped attempts to paraphrase its value yet somehow seemed to communicate something true or even crucial about The Human Condition. The Human Condition being, basically, that we’re alive and have access to beauty, can even erratically create it, but will someday be dead and will not.

Baseball was an art, but to excel at it you had to become a machine. It didn’t matter how beautifully you performed SOMETIMES, what you did on your best day, how many spectacular plays you made. You weren’t a painter or a writer–you didn’t work in private and discard your mistakes, and it wasn’t just your masterpieces that counted.”

Additional complications come from the inherent absence of heartbreak, defeat, and fallibility in the lives of sports’ best players, or at least a hesitance to discuss it in the kind of detail that the best dramas typically engage. If you’re unwilling to look bad, even in hindsight despite hall of fame status, your memoir is bound to suffer. Michael Jordan’s 1998 memoir For the Love of the Game: My Story is endlessly fascinating, if only because it is the all-time greatest basketball player on the subject of himself. While short on specific insights into the game’s nuances, it’s a fascinating look at Jordan’s obsessively competitive approach. The book’s most famous line – “I never lost a game, I just ran out of time” reveals his belief that he is capable of outlasting anyone, and that his greatest on court asset was not his skill set, but his stamina.

Most of the rest is wrought with standard cliches: a line like “Failure is acceptable, but not trying is a whole different ballpark” is betrayed by what we know of Jordan – his believe that he could not be outlasted – and his endless competitive streak, best profiled in ESPN Magazine’s “Michael Jordan Has Not Left the Building”, in which a now fifty year old Jordan grits his teeth in resisting his need for eyeglasses, gambles away millions of dollars, maintains a closet containing 5,000 pairs of Nikes, and collects demeaning news clips of the team he owns, the “worst record ever” Charlotte Bobcats, as the “needle for a hungry vein” that Jordan believes will get his General Manager juices flowing. To say nothing of his frank admission, “I always thought I would die young.”

Perhaps the kind of candor which fuels great writing – truth and fiction alike – is found in most athletes only after they’ve come down from the high of competition, a decade or two after retirement. As Muhammad Ali said, “The man who views the world at 50 the same as he did at 20 has wasted 30 years of his life.” The exceptions who write well in real time during their pro careers are few and far between: Jim Bouton, R.A. Dickey, the inexplicably articulate Dennis Rodman of the shockingly compelling Bad As I Wanna Be. There’s a tricky paradox to debate within each of these books: on one hand, there is a wordless beauty to the acts of sport – the poetry in motion – which defies depiction on the page. Yet just as one would practice free throws in a driveway, there is an impulse within sports journalism to keep at it, go on practicing by crafting and editing new sentences with obsessive fervor. For comparison, there are writers who cover dancing, trying to find clever metaphors for the flamenco, the Texas Two-Step, and the old soft shoe. But dance reporter: damn. That seems like it’d be a hell of a tough racket.

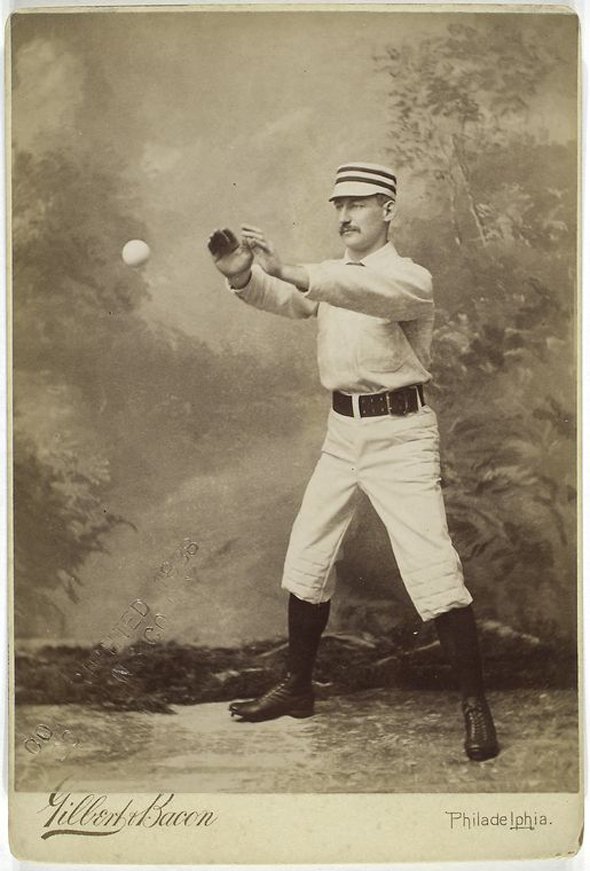

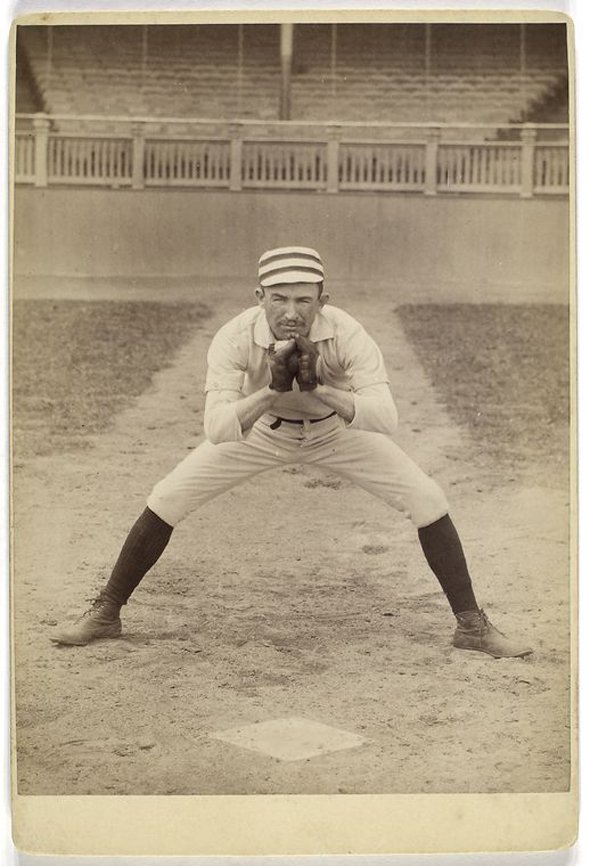

All old-timey baseball images seen here can be found in the New York Public Library’s digital archives.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.