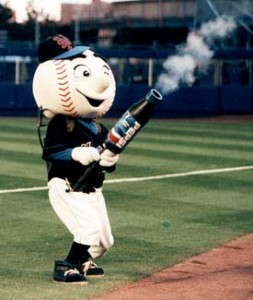

On Saturday afternoon I watched the gaunt and jaunty Mr. Met trot out from right field to unleash an onslaught upon the ambivalent, half-filled stands of Citi Field. Those of us willing to watch the Mets fall to the Kansas City Royals in a 4-3 twelve inning war of attrition rose up and offered our richest enthusiasm of the day. Not to a swift diving catch or seam-splitting dinger. These vigorous roars of excitement went to a person (gender, race, and creed unknown) who donned a Mets uniform and large plastic headgear in the shape of a baseball. Yet the baseball – and this is key – sports a friendly and enthused face, cartooned and impish in design.

Mr. Met, armed with his trusty Pepsi-branded t-shirt cannon, gave hope where there had been but fatigue and apathy. He fired with jolly octane about a dozen rolled up merch wads into the crowd, peppering the more expensive seats first, then doing the best he could in jettisoning a few up to the promenade and mezzanine. I couldn’t tell you what the shirts look like unraveled, as no one in my section was fit to lunge for one.

To my right was a bug-eyed father in bicycle shorts, seemingly unfamiliar with baseball’s nuances, who gave loud hopeful moans of “Oh! Oh, oh, ohhhhhhh!” at each crack of the bat, for even the most obvious foul balls and pop flies. To my left sat a season-ticketed madame who closely resembled Dr. Teeth from The Muppet Show, dressed in Mets pajamas, and became the first person in my life to call me a “schmuck” to my face, after I briefly blocked her view of Anthony Recker’s first strikeout of the day.

A recent Forbes survey profiling 2013’s most popular sports mascots – in which the joy of children is quantified by the degree to which it made rich white men more money – speaks fondly of Mr. Met’s treatment by his team, who “have made more use of him in ads during their recent Madoff-challenged years,” so much so that he “ranks second out of all mascots in fan requests to interact during games.” We’ve all had times in our lives when we’ve asked someone to interact with us, and we know how much it means to have someone with whom to interact. Mr. Met even keeps it local, resisting the high status allure of Greenwich and Scarsdale: the first bloke to don the costume is today a sassy Soho retiree. Moreover, most mascots aren’t as anthropomorphized as Mr. Met. He’s a figure so humanized that he could be your neighbor, or cohort in a local orgy.

The etymology of mascots stems from the French masco, meaning sorceress, and later mascotte, meaning talisman or that which is to bring luck. Certain mascots still try to rally good fortune to their teams. The “Philly Phanatic” of the Philadelphia Phillies puts hexes on umpires, and provokes heated arguments with the players and coaches of visiting teams. Others are meant to simply quell the masses stuck with a struggling team, such as the Los Angeles Angels’ Rally Monkey, or the beloved running of the Sausages patented by the floundering Milwaukee Brewers.

In researching the unique creatures and likely felons who roam the Mascot Animal Kingdom, I wondered if the book publishing industry might not benefit from the same karma that mascots bring to sporting events, car dealerships, heavy metal concerts, and NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory.

Superstition? Mos def. Yet it seems quite possible that the literary world often takes itself too seriously. Cue the stream of editorials debating whether or not the literary world takes itself too seriously. Written in italics on websites which bravely publish long sociological missives, while making their quarterly margin on banner ads for dick pills and slideshows of Blue Ivy Carter’s 14 Greatest Poops.

Still, I hope to see mascots enter the literary world with tempest, kicking off sales conferences and pumping into the air a plush fist which holds a review copy of the next Amy Tan or Wally Lamb joint. Literature in fact already has an announced “technology mascot” in Margaret Atwood. Atwood is everything you want in a mascot: eccentric, enthusiastic, able to roll with the punches. And by being a respected older female artist not yet put out to pasture in her early seventies, she is a creature as rare and foreign as a six foot tall hornet, or flame-retardant gorilla.

For most publishers, the most directly correlated mascot option is apparent. The mascot of Random House would likely be a performer wearing a large foam rendering of a suburban three-bedroom covered in question marks. Or a Boxcar Willie type prone to breaking and entering into abandoned post-bubble homes. “Make my house a Random House!” says Willie on the package of Frosted Mini-Galleys which sport his visage on their box front. The Macmillan imprint Picador could dress an intrepid Tisch student in a bullfighter’s outfit and have them prance around your local bookstore, shaking red blankets and spearing the café pastries. You could even rent a homeless geezer resembling Hemingway to stand alongside and cheer Pilar the Picador on. For Simon and Schuster, the choice is clear: team up songwriting folk legend Paul Simon with famed German soccer coach Bernd Schuster, and watch those copies of Proof of Heaven fly off the shelves ’til kingdom come. Penguin would presumably utilize a parrot of some kind.

However today’s bookworm titans choose to slice it, the message is clear: literary mascots will feed and clothe the homeless, in addition to giving them the role-playing fantasies of a lifetime. The only remaining question is how our tastes for book caricatures will evolve over time. Is Percy, the Price-Fixing Panda far behind? Alongside the Indebted Internship Iguanas, Igby and Indignity? For now, it seems that our literary canon remains full. Only our t-shirt cannons must now and again be reloaded.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.