I joined a cult this week. Pretty fun. Well-organized. Addictive, sure, and the acolytes are rabid, but the devices are user-friendly, and I’m starting to make friends. If I prove myself, I may even climb the ranks toward a higher ranking and be given new privileges. We even have our own app. That’s right, infidel: there’s an app for us. And it may yet save your soul.

The bloodthirsty horde I’ve partnered up with goes by the quaint name of Goodreads, but I assure you: within its confines, we’re all breaking bad. Each moment within this bastion comes another issuing of awarded “stars”, bestowed and rescinded with militant austerity, like some power-mad generalissimo tearing badges off breast pockets. Goodreads looks to foster a community of readers, one upon which aspiring writers and a publishing industry in search of new veins has sought to capitalize. A combination user review compendium, meeting hub, insider trading module, and Wiccan battleground, Goodreads is a haven which endorses collective soul, and strength in numbers. Yet up to this point in my life of tabulation, I’ve only ever practiced the site’s particular brand of dark magic solo, and in secretive anonymity. When it comes to filing my own internal Dewey Decimal System, I’ve always been a lone wolf.

From the moment I started sorting my columned star rankings of books “to-read”, “favorites” and ones long ago digested, I recognized the site’s tinkering pleasure of sort n’ filter right away. Some of us are genetically wired toward Goodreads’ acute brand of artistic evaluation. As a forum, it is individually numerical in ways which unite our hive minds into a consortium, for results both utterly trivial and genuinely rapturous. Nowhere else online better distills the impulse to learn which titles come out on top in catalogs called “Smut for the Smart“, a showdown of 1,192 entries entitled “So You Love a Bad Boy or Tortured Hero“, or the admirable “Scars are Sexy: Books with Imperfect/Disfigured/Disabled Heroes“. And no, not all of the lists are erotic, though if you can get off to Popular Conflict Zone Journalism Books or Carl Sagan’s Reading List, more power to you.

An embarrassing portion of my twenties has been spent on stuffy internet message boards, debating pop culture minutiae with rubes to whom I felt superior. L’Avventura vs. La Dolce Vita. The Shivvers vs. the dB’s. “Macho Man” Randy Savage vs. “Rowdy” Roddy Piper. (The correct answer in all three scenarios, by the by, is the former.) To now do so with books is a sensation bordering on soccer hooliganism.

For me, obsessive cataloging has long-standing sex appeal. In fourth grade I watched two popular boys together form equally weighed lists in their shared notebook. On the left hand column: the duo’s picks for history’s all-time best baseball players. On the right: their ranking of the most powerful cards one could own as a player of Magic: The Gathering. Both boys become varsity pitchers, and I don’t mean that euphemistically. Watching the soon-to-be varsity boys nerd out in those twilight years of childhood just before you realize anyone’s watching you be weird was one of the formative moments of my life. I saw them having fun codifying their own opinion of the world into precise order. Recall that the first sentence of Michel de Montaigne’s On Friendship is “I was watching an artist on my staff working on a painting when I felt a desire to emulate him.”

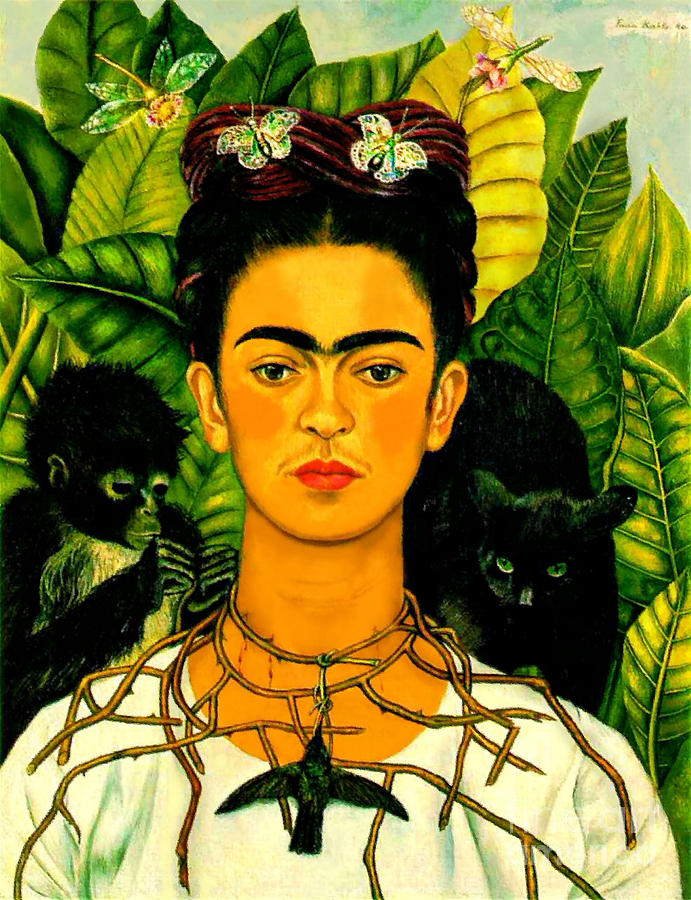

In another era I might have stacked pencil drawings of great paintings onto graph paper to determine (purely for myself) where “Self Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird” ranks among the paintings of Frida Kahlo (no worse than #5, no lower than #9). Interest in statistics aside, I went on to be surprisingly bad in math, save rapid parlor trick ability in arithmetic, used to calculate tips in cabs and restaurants. There I’m free from my usual spatial amnesia in Geometry and Trig: the confines of my coordinates. My room is clean, but not compulsively so. Yet analyzed ranking and list making has always made a mortifying amount of sense. The sensation I pull off of clicking “New Sheet” on Microsoft Excel is akin to what addicts feel upon lighting their first Pall Mall of the morning.

These peccadilloes make me an ample target for sabermetrics, a science I enjoy more in theory than in practice. The story of Bill James is an inspiring one, and his approach is dead-on and often quite fun. A stathead nerd not only explains to the jocks why the world is unfair, but ends up making the world fairer in turn. Better living through chemistry. In theory. Players are still mercilessly judged, and the computer evaluating you still probably doesn’t care how nice a guy you are in the clubhouse. Ironically, revenge of the nerds comes in this instance only for the nerds who on paper turn out to be exceptional athletes that have been exceptionally undervalued. Amidst the metrics of WHIP, BABIP, and VORP, you may still end up judged by the quality of your burp.

And so for most, fantasy baseball remains pure fantasy, and perhaps all the sweeter for it. Robert Coover strikes this match in one of the sport’s best fictionalizations, The Universal Baseball Association, Inc., J. Henry Waugh, Prop. The plot is Google-able, but allow me to serve the modern writer’s role as search engine hood ornament. The titular Waugh is a loner accountant. Not lonely exactly, though most loners are now and again. Still, he’s a solo artist, and one who winces impatiently when the bodega clerk tells him, “Better take it easy. You been looking a little run down lately.” Such barbs sting for lack of sensitivity: for a solo artist like Waugh, a trip to the deli can be a pilgrimage.

Into the wee small hours, Henry vigorously carries out the fifty-fourth season of a pre-digital fantasy baseball league in which he is the only player. Inventing his own leagues, teams, and rosters, he even writes certain players entire biographies: like Waugh, these tiny characters tend to operate on frenzied high-low jags, equal parts bombastic, sentimental, jolly, and saturnine. Carrying out each inning with the roll of dice, Waugh lands on an improbable dream: Damon Rutherford, a promising rookie pitcher starts throwing perfect games, a feat as rare as a hot handed craps player tossing a night of straight sevens. On the verge of this supreme feat for the first time, Rutherford is composed, and Coover’s wry smile sets in as the line between Waugh and his inventions blurs:

“Damon warmed up, throwing loosely to catcher Ingram. Henry watched him, felt the boy’s inner excitement, shook his head in amazement at his outer serenity. ‘Nothing like this before.’ Yes, there was a soft murmur pulsing through the stands: nothing like it, electrifying, new, a new thing, happening here and now! Henry paused to urinate.”

Outer serenity is a fine name for that which separates our world’s cool customers from its neurotics, and often its team players from its loners. The linked fates of Rutherford and J.H Waugh (Yahweh – get it?) prove brutal in their humor and honesty. Coover, a long-toothed champion of metafiction, is perennially concerned with why we tell ourselves stories, and is willing to do bad things to his characters in order to take you down that rabbit hole of inquiry. It might be a stretch to equate Universal Baseball‘s 1968 pub date with the historic tumult of that violent year – but in hindsight, it does feel like a beautifully rendered hangover from the summer of love. Were Waugh a character on Mad Men, he certainly wouldn’t be Don or even Pete Campbell. If anyone, he’d probably be a cross between Freddy Rumsen and Paul Kinsey. Bloating around the middle, thinning out on top. Gentile, if a bit grandiose, Waugh can still get a girl from the bar to come home with him now and again, especially if the bar is paying said girl to hang out there.

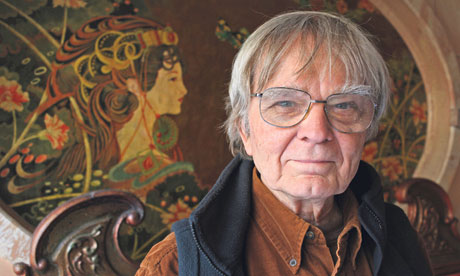

I don’t wish to make fantasy baseball and a literary pow-wow like Goodreads out to be synonymous, even if the 81-year old Coover looks like he could be Bill James’ stern older cousin, growing up on opposite ends of Iowa. James was the last man in Kansas drafted to fight in Vietnam, while Coover could have been the pin-up model poster child for 4F cases. The realities of ranking and cataloging books aren’t entirely germane to the balancing act of managing even a fake squadron of athletes, especially if you live in Brooklyn. After cutting John Lackey and Dan Uggla from our fantasy squads, most of us aren’t likely to run into them at parties. Yet giving an acquaintance’s book two stars or less on Goodreads seems a surefire way of taking yourself off their guest list. But really, what drop-worthy players in name alone: “Lackey and Uggla”. Probably nice enough chaps to have a beer with though.

What is most disarming about Goodreads, charmingly so, is that it takes a humbling, obsessive-compulsive practice, one which I have for too long branded an illicit, shameful time-suck, and makes into something open and rather freeing. On it best day, for its best users, it expands the world rather than contracting it. Just a few days in, I’ve already had some really sweet-hearted offers from friends and strangers alike. Maybe this is one of the truest pleasures of adulthood: you stop watching varsity-to-be have your fun for you. You meet the other solo artists and find some joy together. You inspire one another, and argue your way into precise order. You find out what electrifying new thing will be born from soft murmur. Lone wolves like the cold, and the cold is good to us most nights. But soon enough the bodega beckons, and each gets hungry in due time.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.