“You can make me mount the scaffold, but I can get you where it hurts, and that is exactly what I want.” – Heinrich von Kleist, “Michael Kohlhaas.”

The first thing I noticed in the Times Obits in March, I’m a little embarrassed to say, was not the man’s accomplishments, but merely his name. Namely, his name wasn’t his name: the copycat’s original had died nearly 200 years ago under wildly different circumstances and causes, and for vastly different reasons. So I thought at the time. The copycat, the last survivor of the final interior plot to assassinate Hitler, took the name of one of the most enigmatic and underappreciated (at least on this side of the world) German Romantic writers. Certainly there was no way these two could be related, even abstractly, and even if they were from the same family, their lives meant different things to global culture and history. So I thought.

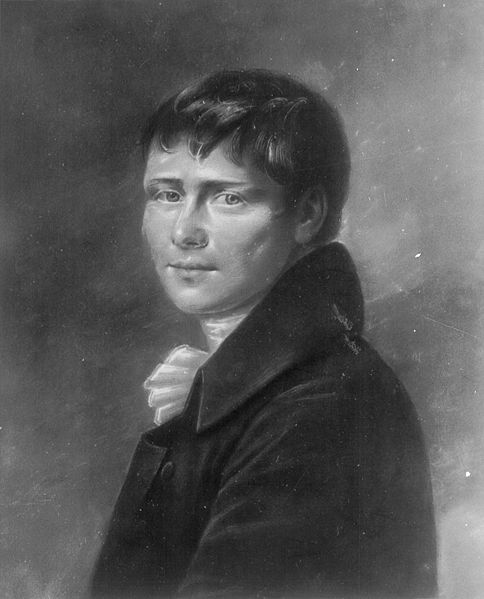

The name I knew was Heinrich von Kleist, the (in)famous German Romantic writer who fell out with Goethe, whose essays and stories anticipated tenets of both Kierkegaardian existentialism and Freudian psychoanalysis, and who Kafka regarded as one of four writers to be a “true [blood-relation.]” His stories are night-terrors of the individual mind struggling in a world of absolutes, tragically fixated over the plasticity of reality and history and our inescapably passive position in the jurisprudence called the world. His most famous tale, Michael Kohlhaas, the story of “one of the most upright and at the same time most terrible men of his time,” was recently adapted into a film starring Mads Mikkelsen. More on this later.

But in March, the 90-year-old Ewald-Heinrich Von Kleist quietly passed away in his home. Ewald was the last known survivor of the July 20th, 1944 interior plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler. Ewald-Heinrich’s father, Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin, encouraged his son, then 22, to detonate two hand grenades hidden in his palms at a presentation of new uniforms for Hitler. This didn’t happen. Hitler kept putting it off, and the Gestapo were closing in on the conspirators. On July 20th, another plotter, Claus von Stauffenberg, concealed a bomb inside a briefcase and, after leaving the conference room to answer a planned phone call, detonated the explosive. One of Hitler’s men unwittingly moved the bomb away from Hitler, shielding him from the blast. Three officers died. Hitler’s pants were shredded.

Kleist-Schmenzin and his son were opponents of Nazism early on—the elder Kleist flew to England in 1938 to ensure that Chamberlain would back the resistance group if a coup was staged against Hitler. Chamberlain’s people told him he was flirting with treason. Stauffenberg and Kleist-Schmenzin were executed shortly after the assassination attempt. Ewald-Heinrich evaded trial because of a lack of evidence. He was imprisoned at a concentration camp and eventually released. Temporarily homeless after the war, Ewald-Heinrich went into the publishing business, and eventually established one of the leading publishing houses in Germany. He joined the Order of Saint John, one of the oldest chivalric orders in Europe, and was honored as a Knight of Justice in 1975, a title his father held 40 years earlier.

The Kleist family is old Pomeranian Prussian aristocracy, and many of their men became military officers, with a smattering of poets and inventors. Heinrich arguably occupies the most anomalous position in the family. After fighting against Napoleon in 1792, he abandoned the military seven years later to pursue university studies, where he encountered Kant. His “Kant Crisis,” as scholars dubbed it, erased his faith in the Enlightenment’s ability to justify God and his abilities to understand the world. Kant replaced it with an understanding of the limits of individual perception and knowledge. It was truly a crisis: Kleist ended his life in 1811, and the twelve years after he rejects the family tradition is a see-saw between desperate attempts to get back into the army (so he can die, one scholar notes) and feverishly writing stories and plays. Heinrich, too, was a publisher: in 1810, he founded the Berliner Abendblätter, a free paper in where he published criticism and some hilarious anecdotes, but to little success.

He gave us eight stories, six plays, and a handful of fragments and philosophical essays whose characters traffic in incredulous tragedy, the paradox between appearance and reality, and the uncanny. In “The Earthquake in Chile,” Josephe, the daughter of wealthy parents, is moved to a convent as punishment for her affair with Jeronimo, but when she collapses on the steps from labor contractions, she’s condemned to burn at the stake. Jeronimo is set to hang. Both escape death through God’s intervention via the earthquake, or so the narrator would have us suspect. As the survivors faction off, the couple meet the sympathetic Don Fernando and his family. A friend of his wife’s, Donna Elisabeth, reminds Fernando just who these people are while en route to a church. “What’s the worst that can happen?” he asks. As they give thanks for His intervention at the church, one of Josephe’s servants sees her in the crowd and incites a mob. In the ensuing confusion and violence in both the name of God and against him, the couple is violently murdered, along with the wrong baby: Don Fernando survives but loses his son, and adopts Philip, Josephe and Jeronimo’s newborn. He “reflected on how he had come to be blessed with each,” Kleist writes. “[It] almost seemed to him as though he ought to be happy.”

The catastrophe that saves Josephe and Jeronimo also delivers their doom, yet throughout the narrative, we are meant to understand both the lovers and the mob, and how they use God to make the earthquake meaningful. Though Kleist leans us more heavily against the murdered than the murderers. It’s this refusal from the narrator to mime the judging God—to cement our morals and reasons in discrete spaces of understanding—and hover us above a comfortable, emancipatory ending that lands us in meaninglessness, the make-up of reality as only cacophony draped in meaning. Kleist’s point here is a matter of perception: the overruling notions of “good” are determined by the ideology-in-play, and those who pursue their desires outside of this jurisdiction are as good as dead. This is the true crime.

I want to suggest that the philosophies Heinrich could not reconcile in his lifetime were carried through by his 20th-century relatives, but I should tread lightly. It may seem that I’m unfairly linking the literary activities of a man, whose suicide is characterized by a selfish myopia, with his distant relatives whose desire to suicide, we might argue, is justified selflessness. But this is Heinrich’s point. Exactly why and how violence is justified into virtue, and how extremism can turn from sin to sanction, is a difficult question. It spares no one a cross-examination, and challenges our arrival at a priori understandings of morals.

The world had to re-think the possibility of evil with Hitler’s arrival. It radicalized our notions of civilization. And if the machine of civilization is underpinned by Reason which, in turn, helps ordinate the murky world of morals, what was Hitler, this crazed figure who both rebuilt Germany and epitomized the possibilities of evil? What is justice?

* * *

Which brings me back to Michael Kohlhaas. I want to think through a bit about the fogginess of the personal, and what it means for collective ideas of justice. The fair- and noble-hearted Kohlhaas has it made: the devoted wife, the castle, the children. He lives honestly, raising horses and treating his servants well, but an incident at the Junker Wenzel von Tronka’s castle turns Kohlhaas into, well, I’m not so sure. In Kleist’s words, Kohlhaas’s unwavering “sense of justice turned him into a thief and a murderer.” Tronka forces Kohlhaas into leaving behind two horses the former drools over as a deposit for letting the latter pass without paying a tax—a trumped up claim—and promises to return them once Kohlhaas returns with proof of ID. Kohlhaas decides to let this one go. But this is Kleist as the grim ironist. A trick is being played on us as well.

Kleist shows us the destructive effects of the law: Kohlhaas agrees, well-knowing von Tronka has invented his injunction, because there is the possibility that there could be such a law. You’ll have to pardon this example, but this is Kohlhaas playing into a Rumsfeldian known unknown. Kohlhaas’s righteousness is also molded by the very discourse and system that subordinate him, it empowers and disables him. The first thing he does upon arrival in Dresden is seek reassurance about the illegality of von Tronka’s claim. When he returns to von Tronka’s, he finds his horses worked to the bone and the squire he’d left with them gone, having retreated back to Kohlhaasenbrück. Kohlhaas demands justice, but when he files a complaint with the courts, it is condescendingly rejected. He soon discovers that von Tronka has family in the court system. What follows is a fanatical, almost maniacal story of destruction in the name of personal justice. But, as in “Earthquake,” we are meant to doubt the successes Kohlhaas’ believes will be promised to him: he only burns and pillages towns with a mob to get the attention of higher courts, those same courts who buried his claim in bureaucratic nepotism and maze-like language.

Kohlhaas’s “war,” in one way, is a war of political rehabilitation. Here we can see where Kafka may possibly have taken notes from Kleist: Kohlhaas wants to reinstate the harmony of feudal bureaucracy that, we can only assume, was working splendidly before von Tronka, though that same system is shown to have always kept its subjects down under the auspices of citizenship. The failures of both religious and juridical definitions of virtue and person lead, or reduce, Kohlhaas back to something close to a primal understanding of justice.

What’s most troubling—and, perhaps, the most amazing effect of Kleist’s prose—is how empathetic we are to Kohlhaas’ violence, fully knowing that he is, if we are to split hairs, overreacting to the loss of his two horses. We simultaneously chastise and celebrate Kohlhaas because it isn’t just the horses. It’s the law, the despicable inherent in the abuse of power. The world that allows structures of power (and truth) to maintain ideals of moral purity which also turn men into von Tronka and politicians.

It is here when we understand Kohlhaas less as a character, a representation of a socialized human, and more as an idea; Kohlhaas is an allegorical figure that shows us the fall out from Godly Reason’s (read: the law’s) definition of what a person is, and what happens when our inscrutable instincts take over. After a complete and total loss, we seek only retribution, even if it means felling our physical selves: Kohlhaas indeed mounts the scaffold, despite his knowledge of a very damning fact about the Elector of Saxony from a mysterious gypsy which would ensure his freedom, so he can get the government where it hurts. But just because Kohlhaas becomes more of an idea than a person, a vitally emotional connection is not out of the question. Kohlhaas’ life is an embodied question. Would we not do the same upon total fallout of our lives?

A darkly comic digression into backroom juridical dealings frames Kohlhaas’ death as the fault of warring states trying to use him as political leverage. From the perspective of Brandenburg, Kohlhaas’ home jurisdiction, which is under the sway of a Poland at war with Saxony, Kohlhaas is a martyr. But in another light, and what I think is the core, Kohlhaas is the figuration of the necessity for individuals to stand against injustice as surety for the future, even if it “illegal.” “But in Mecklenburg,” Kleist writes, “in the previous century, there still lived a few happy and stouthearted descendants of Michael Kohlhaas.” Kohlhaas chooses death in service to the idea of justice and retribution. His suicide is for a principle, an idea, a body beyond the physical. Kohlhaas is legally executed because he disrupts the Imperial (read: Catholic) peace, a treasonous act, but we don’t understand Kohlhaas’s psychology as such. When is treason justified?

* * *

The Order of Saint John, where the 20th-Century Kleists are knighted, also has its jurisdiction in Brandenburg. And because of our history, we would want to say Kleist-Schmenzin’s commitment to suicide is a commitment to justice, which I completely agree with, but I think this coincidence shows us something more important. The idea that one needs to stand against injustice at whatever cost almost seems cliché to us, but we should remember that the Kleists had to perform their philosophies in secret. Kleist-Schmenzin and his son were, in a way, not German enough under National Socialism, and Heinrich not only wasn’t Kleist enough, he wasn’t human enough. In his suicide note, Heinrich moaned that the world had nothing left to teach him. It seems to me that Heinrich committed suicide because he could not be a human as the world provisioned. But we can only see this through the lens of history, and I can only posture and celebrate the Kleists through it.

Truth-in-itself is an illusion, an idea that we are more than familiar with, and for these Kleists, the path of how moral scruples became Moral Scruples as understood by their overruling ideologies must have tormented them. And the three of them committed themselves to death, to failure. So, perhaps, their stories are not records of success and moral purity, but of failures. As seems to be the trend of the Kleists, these failures are paradoxical, in that they have the effect of success, of transcendence.

When I talked to a friend about these Kleistian connections, I was deeply embarrassed by how caught I’d been in my tape loop of the historical Kleists. My friend made an equally, if not more important, critical insight that the Kleists’ unwavering commitment to personal justice was more timely than ever. It made me realize how important it is to confront and affront our current ideas of personhood, to continuously question where and who we are. And, taking lessons from the Kleists, to fail. Twelve years into the Era of Never Forget, aren’t Kohlhaas’s black nags our e-mail drafts? How did we let them give us the atomic wedgie that was the Patriot Act, legal precedent for NSA activity? What could we have done? The ideals of America gave them permission to snoop: the very machine of our enfranchisement—our vote—disabled us. But wasn’t our gift accidental? Half of us didn’t vote for that guy. Wasn’t it because we were simply American? Cue collective depression. We were Kohlhaas when the municipal government ignored our complaint, and we seethed, we lamented on our social medias, posted all the news stories on our Twitters and Facebooks. But Kohlhaas, and Ewald, remind us that we should, at the least, be committed to ensuring justice in the face of extreme political—and personal—disenfranchisement.

It seems that many of us may feel like the Kleists, insofar that we’ve got a government seemingly working against us, and we’re trying to find a way to make our vote matter on our end. But what’s different is that there we are a collective. Kleists’ collectives were secretive, but we are publicly bound by our dissatisfaction. Yet, at least for me, something lacks. I may be too much of a utopian, but the fact that dissenting factions, their loves for Tea, Coffee, and sit-ins notwithstanding, bicker over the right set of values before considering how, perhaps, the very ideals of liberty granted to us may actually keep us depressed tells me there is something else we can be doing, or thinking about at the least.

I wanted to write this essay in effort to think through the possibility of really living philosophy, and how it would—if it could—manifest itself. And, additionally, I hoped I would help expose Heinrich to an audience more familiar with that other K, Kafka, even though much of me wants to squander the joy and brilliance of Heinrich for myself. I thought this essay was going to end here, a think-piece of what the death of Ewald-Heinrich von Kleist means beyond the already transhistorical import of his life. It brings me to capital-F Failure, and the strings of failures that make up philosophy and art.

The naïve, nigh-mystical point I want to suggest is that the philosophies and behaviors Heinrich makes in his fiction are, perhaps, chemical structures in the Kleistian water, but another point I would like to heavy-handedly impose is the importance of failure, and not totally in the sense that failures allow us to try again. The conventional notion of failure as a space that allows us to replay still suggests that success is an option in our lifetime. Failures are possibilities of success beyond one span of consciousness. Kleist-Schmenzin and Ewald lived the philosophy their nineteenth-century cousin experienced in his writing, one in which Heinrich failed to experience in his present. But in our present, 2013, Heinrich is Kohlhaas: his work—and history’s narrative—helps justify the 20th-century Kleists’ morals and motives, and their legacies enable them to become Kohlhaas as well. And the pervasive risk that was present was not seeing any kind of return on a commitment to failure. In this light, Ewald-Heinrich was lucky. He didn’t have to die to see his ideal become real.

How can we fail? I think Kleist needed literature in that way we’re familiar with writers of the day: “I can’t do anything else but write,” “I don’t know how to do anything else,” etc. While I sometimes cringe when I hear and read these sentiments, I can’t help but wonder if they’re effects of what Kafka and Kleist are so disabled by: the illusory yet very real iron fist of the law. We hear these phrases and we tend to connote them with dedication, perseverance, etc.—a sentiment of an on-the-way towards success. Why do we not first consider them failed humans? It seems that Kafka and Kleist had to fail as people in order to write, their machines of repairing their places in the world. The category of “person,” their work shows us, is provisionally constructed. They had to stop participating as proviso humans to be Kohlhaas and Josef K. I mean, if Gregor had not totally failed as a Samsa, would he have ever realized the true crimes of his reality, would he have transcended the human? Gregor’s failure, and Kafka’s and Kleist’s, are transcendent, they push them beyond the limits of the provisional and juridical into true accession to the personal, that utopia where personal is not political, where we are not vehicles of our ideologies but truly collective.

Since success, at least in America, is what we are brought up to strive for and place belief in, I want to suggest that failure is a viable option. I think we have to fail, and not only in our artistic efforts as Beckett advised us as undergraduates. It’s not a stretch of the imagination to consider people like Snowden a failure. He’s a failure in the jurisprudence of America, his provisional construction, but now he is moving towards something like a principle, like Kohlhaas. We might as well consider Snowden as good as dead because, like Kohlhaas, it’s his failure as a legally recognized American that’s paramount here.

How will we question and reproach von Tronka’s trumped up injunctions in the face of the huge risk that promises: the destabilization of our provisional constructions, our failures as Americans? Maybe those of us who are not resigned to “I have nothing to hide, go ahead and look,” are looking to fail like Kohlhaas, like Snowden. Failure can re-enfranchise a sense of personal justice. It puts us in a place where transcendence is the only option.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.

1 comment

The preceeding easily ranks among Vol. 1’s best pieces of (non-fiction/essay) writing. Well said, Mr. Chang.