Tomorrowland

by Joseph Bates

Curbside Splendor; 226 p.

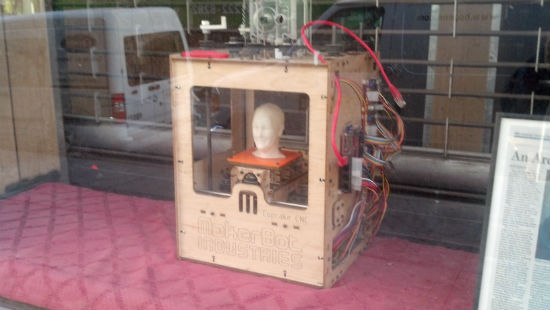

On my morning commute, I pass a storefront space where video conversions are the business’s stock in trade. What was a cutting-edge feature for a few decades — convert your home movies to VHS! Convert your home videos to DVD! — has become something more of a speciality market today. They seem to have embraced this, placing in their window one neon sign and one surreal robotic sculpture, the sort of thing that wouldn’t have looked out of place on a character’s desk in a 1950s B-movie. Sometimes you’re overtaken by nostalgia, and sometimes you let it be the cause of your propulsion. That sort of nostalgia-riding can lead to powerful things in fiction: consider the way Patrick Somerville plays off pulp-technology archetypes in his The Universe in Miniature in Miniature, or how Steven Millhauser manipulates notions of the early 20th century in his short fiction.

Many of the stories in Joseph Bates’s Tomorrowland come from a similar place. Some openly use science fictional elements: a time machine used by a writer in an attempt to make his past better; a kind of television receiver that summons up images of parallel universes. Others, such as the title story, focus more on the memories of how tehcnology was expected to be — to borrow the title of the late Frederick Pohl’s memoir, the way the future was. And still others — “Boardwalk Elvis” and “Yankees Burn Atlanta” — zero in on nostalgia itself, and the ways it can both enervate and illuminate.

The reference to “Eisenhower-era comforts of the future” in the opening line of the title story gives the reader a sense both of when they are and when they’ll be hearkening back to. The story’s protagonist is middle-aged, old enough to remember the era for which he’s meant to be nostalgic even as he’s young enough to be employed clearing out his detritus. Alternately: it’s the future of the 1950s juxtaposed with the economic crisis of the 00s, with all of the discontinuity that that implies. And while “Mirrorverse” is less explicity about its influences, the description of the device that sets its plot in motion — specifically, one that allows the viewing of parallel universes — also evokes that period of design:

It has oculars like a two-socket microscope, but the body resembles an ammo box, with curly wires coming off like you’d expect to find on a moonshine still, and a few round dials on the front of it, and a couple of rectangular controllers with thin cords connected on the sides.

Elsewhere, Bates turns his attention to politics. “Bearing a Cross” has a kicker of a second sentence: “To our credit, I think we went into theocracy with the best of intentions.” It’s about how the residents of a small town vote for a mayoral candidate promising a return to prosperity through the aforementioned system of government; though the satirical target isn’t a particularly small one, Bates takes a particularly over-the-top approach to it, leading to a story that begins as satire adopting a progressively more grandiose scale as it reaches its denouement — from classic Twilight Zone to South Park, basically. “How We Made a Difference” features trick-or-treaters citing political jargon, conflicted would-be parents, and unexpected turn-ons; it begins as a satire of right-wing politicians and gradually evolves into the sort of satire where no one emerges unscathed.

That all-encompassing approach is characteristic oc Tomorrowland. In “Future Me,” the increasingly Byzantine structure of the narrator’s future selves and past selves meeting, voyaging in time, reliving past glories, and seeking to overcome failures — echoing Matt Singer’s review of World’s End in terms of the ways that nostalgia can be more damaging than the uncanny. Tomorrowland is often charming, and proceeds briskly — but it never loses sight of the anxieties that motivate many of these stories, and it’s chiefly for that reason that it endures.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.