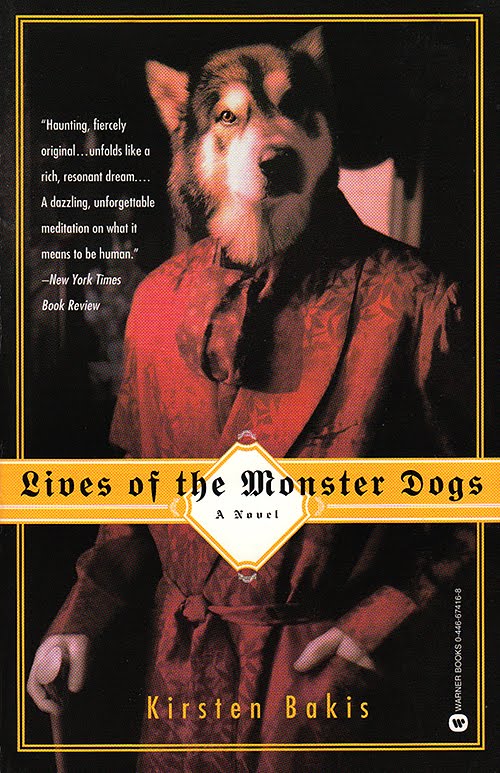

A novel with the title Lives of the Monster Dogs isn’t something one soon forgets. I’m not sure when the first time I saw Kirsten Bakis’s novel on bookstore shelves was: I’m guessing it was a while ago, before I’d developed the compulsion to buy books that pique my interest at a moment’s notice. Something held me back, and I don’t quite know what that was: a fear that, for that I was intrigued by the novel’s premise, I’d be let down.

That premise, by the way? A group of highly evolved dogs arrives in a near-future New York and begins buying up property, courting the media, and pondering their purpose in life. Yes: I was an idiot for not picking this up a decade ago.

There’s a lot to like here: secret cities in the Canadian wilderness, mad science, Tom Wolfe-esque social comedy, and a very unsettling disorder that seems to be befalling some of the dogs. It doesn’t hurt that it has a very tangible sense of place — specifically, the East Village and Lower East Side. (At one point, Red Square is demolished to make way for a castle built to house the monster dogs.) And the monster dogs themselves — some refined, some sinister, some tragic — emerge as well-conceived characters, both compelling and deeply alien.

I’ve had a lot of fun explaining Tatyana Tolstoyana’s The Slynx to people in the last week. “It’s set in a postapocalpytic landscape!” I’ve said in a headlong rush. “And it’s incredibly literary! And satirical! And so very Russian.” And all of these things are true: set two hundred years after society ended in an event that left the handful of survivors immortal and their descendants occasionally mutated, The Slynx is unlike anything I’ve read before. It has its own weird logic, and some of the details — the protagonist works at copying works of great literature that the local despot can pass off as his own — seem perfect.

I also caught up with books by two of my favorite contemporary writers: Javier Marias’s The Infatuations and Jonathan Lethem’s Dissident Gardens. Marias’s novel, as always, is dense and allusive and accumulates a massive amount of power over the course of its length. It opens with discussion of a killing; the narrator befriends the widow of a wealthy man, murdered senselessly; then, things get complicated, and ambiguous. (And excellent.) Lethem’s novel, about three generations of a radical family from Queens, is his most down-to-earth work: there are no surreal elements, and it’s set in the most recognizable environs I’ve encountered in his fiction. On one level, it’s a straightforward family saga, but other elements — the politics, the structure — represent a different sort of departure for him. The fractured chronology of Dissident Gardens occasionally kept me at a distance — certain characters from his ensemble stood out in bolder relief than others — but his ending was (for me) a near-perfect cap on all that had come before.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.