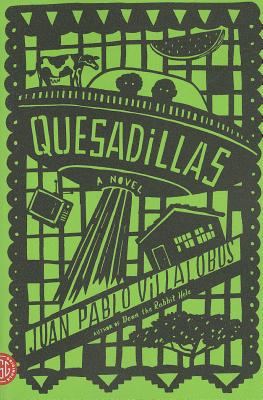

Quesadillas

by Juan Pablo Villalobos; translated by Rosalind Harvey

Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 168 p.

Poverty haunts in meticulous ways in Quesadillas, Juan Pablo Villalobos’s second novel. There are the ways that its narrator’s family can be organized: their academic father has given each child a name rooted in the classics. Orestes, the second oldest, here recounts the story of a life on the margins of society, his parents insisting on their presence in the middle class, the minutiae of his daily life arguing otherwise. Down the Rabbit Hole, Villalobos’s previous novel, also focused on a character at the bitter end of childhood. That character, the very sheltered son of a drug lord, had a particularly isolated perspective, and much of that book’s tension arose from the gulf between its narrator’s blissful view of the world and the horrors occurring just outside of his viewpoint. Orestes is much more pragmatic, possibly to a fault, and it’s the cold pragmatism with which he interacts with the world around him that may leave the largest sting.

Set in the late 1980s, this short novel is structured as the reminiscences of an older Orestes. “[T]he story of me and my family is full of insults,” Orestes warns the reader in the second paragraph. The first of these, one sentence of dialogue long, is memorably profane, and opens the book on a jarring, irreverent note. Orestes and his family live in Lagos de Moreno; his father teaches high school, and outside their home, political unrest unfolds. Within that home, a complex series of interactions has arisen to cope with the family’s lack of money and large size.

We were all aware of the roller coaster that was the national economy due to the fluctuating thickness of the quesadillas my mother served at home. We’d even invented categories – inflationary quesadillas, normal quesadillas, devaluation quesadillas, and poor man’s quesadillas – listed in order of greatest affluence to greatest parsimony.

That simultaneous quality of detachment and stark awareness of one’s own circumstances runs through this book and gives it a significant jolt. Soon, on a family trip to the supermarket, twins, the youngest siblings of the family, go missing. Their disappearance is never explained, but it resonates throughout the family in different ways: a brief and fleeting fame, a lasting trauma, and–in Orestes’s reasoning–more quesadillas for those who remain.

As befits a novel where classical references abound, wordplay likewise occupies a large role. Orestes’s family engages in borderline-philosophical discussions with their Polish émigré neighbors on the wisdom of living in relative isolation. An implicit criticism runs throughout these conversations, but it isn’t always clear who occupies which position; more likely is that, in Villalobos’s word, each character believes they’re putting one over on the rest of the world; the rest of the world begs to differ. That relativity, too, sites nearly every character at a fluctutaing point on a scale: one person’s middle class is another’s poverty. At one point, Orestes does note that, compared with certain relatives, he and his family might actually be middle class, depending on the curve on which you’re placing them. All of which, it should be noted, doesn’t curb the unrest around them or increase the amount of food on their plates.

And so, absurdism gradually creeps in from the edges and makes itself at home. “Why pay for a psychoanalyst when you have a stoner uncle?” Orestes ponders late in the book. Orestes’s older brother spends the novel’s second half discussing theories of what might have happened to the twins; these range from the mundane to the science fiction (specifically, alien abductions). As penance for offense to his neighbors, Orestes is forced to assist them in their work artificially inseminating cows; the result is as detailed as one might expect, realism pushed so far that it becomes bizarre and bleakly hilarious.

Quesadillas is told episodically, each vignette building on the one that came before. It might be due to the profane outburst that opens the novel–”Go and fuck your fucking mother, you bastard, fuck off!”–but at times I was reminded of John Darnielle’s Master of Reality, another novel with a deeply profane opening where a troubled young adult’s coming-of-age is reconsidered from the same character’s older and theoretically wiser vantage point. There’s plenty of heartbreak in Quesadillas, and one hauntingly powerful site of ambiguity. But there’s also humor and intelligence aplenty; for all that it wrenches, it never loses sight of the human core. That might make it sting all the more.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.