Walking through the doors of MoMA PS1 for the New York Art Book Fair can be an exercise in sensory overload. On tables situated in the museum itself, along with the outer courtyard, attendees could purchase anything from limited-edition t-shirts to issues of literary magazines. The space abounded with people: it was simultaneously an artistically-inclined bibliophile’s fever dream and the cataclysmic nightmare of the severely claustrophobic.

Last fall, I made my first trip to the Art Book Fair. In a narrow room on the building’s third floor, a pair of open windows offered a steady breeze and a view of Long Island City’s historical post office. There, a series of pages hanging from the walls and contained within a display case yielded a history lesson in underground publishing and outsider art. The exhibit, which ran over a weekend in September 2013, was Sinking Bear and a Book About Death, assembled by the New York gallery Boo-Hooray and the Portland, Oregon-based art and antiquarian booksellers Division Leap. The exhibit spotlighted one work by the elusive Johnson, who died in 1995 (and was the subject of the 2002 documentary How to Draw a Bunny), along with the complete run of The Sinking Bear. The latter’s nine-issue run, from 1963 to 1964, includes work from the likes of Johnson, Fluxus artist (and grandfather to Beck) Al Hansen, and Joe Brainard. Inside, one can also find a kind of template for numerous underground comics and mimeographed punk zines to follow, along with an abundance of satirical attitude.

Coming of age in the punk scene in the mid-90s, collage was something I took for granted. Zines and flyers borrowed graphics and images from everything from comic books to fine art to bands’ promo photos. These were the raw materials, the basis for something new: information, whether record reviews or a list of bands or something else, was layered on top of it. Sometimes, the source materials were annotated, defaced, or otherwise imbued with commentary — and then the whole thing was run through a copies, sometimes again and again, with all of the blurring and degradation that that process of reproduction implied. But for all of that, it’s also an aesthetic–and yet another example of how the lines between fine art and DIY at its most irreverent have long been blurred–if they were ever there to begin with.

Coming of age in the punk scene in the mid-90s, collage was something I took for granted. Zines and flyers borrowed graphics and images from everything from comic books to fine art to bands’ promo photos. These were the raw materials, the basis for something new: information, whether record reviews or a list of bands or something else, was layered on top of it. Sometimes, the source materials were annotated, defaced, or otherwise imbued with commentary — and then the whole thing was run through a copies, sometimes again and again, with all of the blurring and degradation that that process of reproduction implied. But for all of that, it’s also an aesthetic–and yet another example of how the lines between fine art and DIY at its most irreverent have long been blurred–if they were ever there to begin with.

“Zines saved my life,” wrote Division Leap’s Adam Davis, when asked about the origins of Sinking Bear and a Book About Death. “I grew up in rural Oregon, and one time on a rare trip into town as a teenager I wandered into a place that had punk shows called Icky’s Teahouse, which is no longer there. They had a zine library. I’d never seen zines before. I think before that I thought everything that was published was published by a corporation in New York, and I didn’t know that you could do it yourself. It broke my head open. I sometimes get obsessive about researching the history of certain zines and searching for them, especially for ones that are little known – which is how I got on the track of Sinking Bear.”

Boo-Hooray’s Johan Kugelberg also came to discover both Johnson and The Sinking Bear through other sources. “The first I heard about Ray Johnson was via Jack Smith and underground film,” he wrote in an email. “Sinking Bear was the same, when I was putting together a book on the Velvet Underground a number of years ago, lots of fascinating materials from the NYC underground circa 1960-1965 kept surfacing, nothing was as oddly amazing as the Sinking Bear.”

The Sinking Bear was founded by Søren Agenoux, who would later serve as an editor of Interview. It began as a satirical response to Floating Bear, the long-running publication founded by Diana Di Prima and LeRoi Jones, but quickly became took on a surreal identity all its own. Soon, the mastheads of various issues would begin to list other notable artists as editors; in one, Ray Johnson is credited as “Flying Ed.”; Al Hansen as “Sooper Ed.” Inside can be found everything from winking commentary on the politics of the time to surreal, sometimes ribald comics and collages. At the heart of most of the issues are quotes, sometimes taken from life or literature and, at others, completely fabricated. Read through enough issues and you’ll encounter lines ostensibly (and, in some cases, actually) from Yannis Xenakis, Virginia Woolf, and Stanley Kubrick.

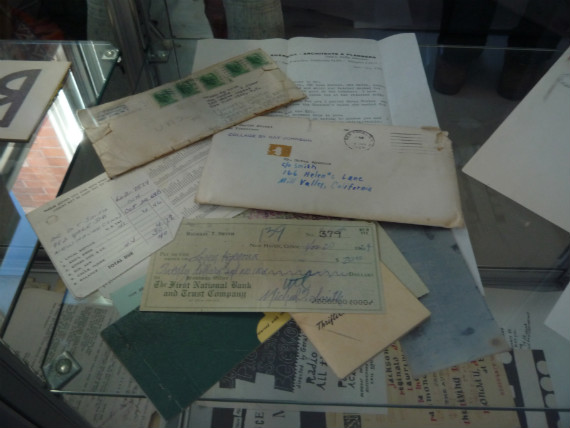

At the exhibit, Davis pointed out that they were, periodically, changing the pages of A Book About Death on display, creating a condition of constant flux. That sense of incompleteness pervades the work; Boo-Hooray’s announcement of the show mentions that “[w]e are showing 12 of the 13 pages Ray Johnson is known to have printed for A Book About Death, as alas, we don’t have a copy of page 4 to show.”

The dialogue between the two works emerges in interesting ways. Most notably, there’s the clean linework of Johnson’s art –and his penchant for collage–both of which are echoed aesthetically in the later issues of The Sinking Bear. Each plays with iconography, both official and cultural. Davis notes that “I’ve always been fascinated by the way that A Book About Death incorporates a serial incompleteness as part of the work–and I feel that there is an affinity there with the subversive collation of Sinking Bear. Certainly both publications were heavily influenced by Mail Art. Both publications are about the fragmentary and incomplete nature of life, and both portray this in a formal way, by employing that idea in the way in which they were assembled and distributed – making them very radical for their time, or for that matter any time.”

The sometimes mocking, always irreverent tone of The Sinking Bear covers everything from the celebrities of the time to feuding art scenes.Kugelberg was quick to point out that “one must remember that these kind of cliques were driven by ridicule, wise-ass-ness and infighting, Sinking Bear certainly has its equivalents in other underground/fandom stratas, be it punk, science-fiction etc.” One could spend days documenting those equivalents and establishing elaborate webs of connection and influence. Just within the small space in the room housing this exhibit, the ways in which artistic collage has influenced a generation of zines far removed from the fine art world is made clear. (That goes both ways: Johnson’s “Venice Lockjaw” pins, for instance, could easily be mistaken for the ephemera of an obscure late-80s punk band.)

This exhibit–and the catalogue collecting The Sinking Bear–can be seen as part of a larger effort to document the artists involved. A new edition of Johnson’s book The Paper Snake was released in May on Siglio Press, and Davis noted that “[w]e hope to publish a book on Agenoux’s work next year, with Fast Books.” For Kugelberg’s part, his immersion into New York’s literary and artistic history suggests a number of other artists and writers waiting for their due. “ Søren Agenoux is endlessly fascinating, but so are many of the ‘marginal’ bohemian people that drifted in an out of this milieu, and who often made things happen as they passed through. I’d love to find out more about Electrah Lobell, I’d love to know more about Beverly Grant, about Irving Rosenthal. Jerry Jennings. The early 60’s NYC needs its own book I think.” If the crowds assembled at last year’s Art Book Fair are any indication, the audience for that book is already there.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.