Valentine’s Sketchbook: A Book Review by an Artist Haunted by Sylvia Plath

by Frances Cannon

I found one still moment between a graduate seminar on melancholy books and an improvisation dance class. I unlaced my salted boots to air out my likely molding feet, formed a small hillock of winter layers on the table in the hall, and retrieved Sylvia Plath’s collected poems from my backpack. I flipped to “Parliament Hill Fields,” which was selected at random by a member of my book group for this week’s discussion. We meet for fun, because we are not busy enough crafting novels, attending seminars, and teaching, and because reading the poems of suicidal writers like Plath and Woolf will cheer us up in the heart of winter in Iowa City. As I read Plath’s line,“A crocodile of small girls/ knotting and stopping, ill-assorted, in blue uniforms, opens to swallow me,” I, too, was swallowed by a crocodile of small girls, although in my case the small girls were undergraduate dance majors, all wearing matching leotards with the insignia of their sorority printed on their flat chests. I read Sylvia’s line, “their shrill, gravelly gossip’s funneled off…” and I, too, was pulled momentarily into the conversation of these dancers,

“on and off medication to lose weight,”

“she’s not Beta material, she’s a backstabber,”

“I heard she’s gone through ten men in the last month,”

I am the only one in this improv dance class in the writer’s workshop, and to emphasize my apartness from these ballerinas, I disfigured my body into unpleasant shapes. I crouched in my knees, lolled my head, shivered the fat of my underarms. I embodied the narrator of Plath’s poem “The Zookeeper’s Wife.” I moved through the room “ugly, my belly a silk stocking/ where the heads and tails of my sisters decompose…”

My grandmother always sends me a Valentine’s package, filled predictably with chocolate, socks, turtleneck sweaters, lavender soap, a pile of books, and a note in her illegible handwriting. Without knowing that I am wallowing through Plath’s poetry, prose, journals, and letters for book group, my grandmother included a very appropriate book in her gift box, Sylvia Plath: Drawings, published by HarperCollins with an introduction by Plath’s daughter Frieda Hughes.

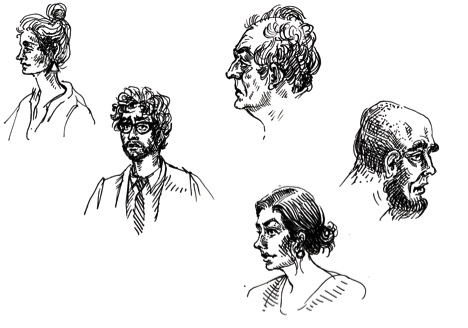

I was delighted, but unsettled. Although this sentiment has become a cliché for young female writers, I feel an eerie connection to Plath and her work, and have been building a mental list of our myriad similarities: we both grew up in in New England in academic households, studied poetry on various scholarships, traveled widely in seek of inspiration, and struggled to find a poetic voice. This book of drawings offered a new reason for me to obsess over the parallels between Plath’s life and mine: she sketched as obsessively as I do now, and in a nearly identical style.

I had to stop halfway through the book to run to my discussion group, where of course, we would be discussing Plath. We meet each week in a bar called the Mill which is quite empty during the day, save for a few brunch-time drunks slumped over the bar like banana slugs. It feels clandestine and contradictory to be reading poetry aloud in a booth which at night hosts Budweiser-chugging quarterbacks and their miniskirted cohorts. On this day we had to shout our lines over pop music, and our waiter repeatedly interrupted the most somber points in our discussion to ask if we needed more coffee.

We are a hodgepodge crew. To name a few: Robyn, a professor of every imaginable genre of writing who possesses the most thorough memory of book titles and author names I have ever encountered, has a castle of black curls large enough to hide a small child. Little Beatrice from Poland who writes about her grandmother’s plum jam and sculpts clay puppets in her spare time is timid in public but vicious in critique.

Magda from Cuba was a lawyer until she offended everyone in Florida. Now she walks her three lapdogs around town in entirely purple outfits to match the streak of magenta in her side-cropped hair. She uses ten notebooks a day due to her theatrically enormous handwriting. Imagine a few more eccentric poets and you’ll have an idea of our reading group.

Our noses took a good half-hour to thaw from the particularly biting wind chill, but we shivered quickly into our discussion, beginning with a handful of poems that Plath wrote after her miscarriage. I had brought my copy Sylvia Plath: Drawings to share, and about an hour into our morose conversation, in order to slow the epidemic of dark comments, I flipped to a random page: a silly little drawing of a “curious French cat.” All at once the table erupted into laughter. After speaking so long about Plath’s lust for death, here was this simple drawing of a cat peeking around a wall, nothing more. I happened to be wearing a black dress which decorated with miniature cats, which somebody pointed out with glee.

One of us noticed that the poem central to our discussion, “Parliament Hill Fields,” was written the same day of this meeting, February 11th, and that “The Zookeeper’s Wife,” the poem in which the narrator is swallowed by a crocodile of young girls, was written on Valentine’s day. Robyn pointed out in an uneasy voice that Sylvia Plath had also committed suicide on February 11th, 1963. We sat on these facts, silent until someone picked up the book of drawings.

The fact that these drawings had caused a spontaneous laughing fit– a moment of absurdity, to a group of stressed-out poets with congested noses on an Iowa afternoon cold enough to split a smile and draw blood, could not be a more positive review of a book. These particular drawings originate in one of Plath’s happiest years, the honeymoon period of her fresh romance with Ted Hughes, before their union dissolved into jealousy, infidelity, mistrust, and before Plath’s depression consumed her life and work. I am glad to see a book celebrating Plath’s creativity and talent, rather than the drama of her life and death. We have heard enough about her depression, her suicide, the tragedies of her miscarriage, and her troubled marriage. There has been little scholarly attention paid to Plath’s visual ambitions, aside from a collection of her early paintings, pastels, and ekphrastic writings, Eye Rhymes: Sylvia Plath’s Art of the Visual, edited by Kathleen Connors and Sally Bayley. This smaller collection, Sylvia Plath: Drawings, feels more intimate and true to Plath’s style. For much of her life she struggled to make her name as a poet and not as a poet’s wife, but this book reveals Plath’s lifelong and largely unrecognized passion. She even told her mother in a letter in 1958 that art was her “deepest source of inspiration.”

Like Plath, my lifelong dream has been to have my art and writings published in The New Yorker side-by-side. As her daughter Frieda notes in the introduction to this book, Plath wrote in her journal while at the writer’s residency Yaddo in Saratoga Springs that her “dream of grandeur” was to have her drawings published in The New Yorker. She echoed this sentiment in a letter to Ted Hughes soon after they met,

“shall I tell you my latest ambition? It is to make a sheaf of detailed stylized small drawings of plants, mail-boxes, little scenes, and send them to The New Yorker which is full of these black-and-white things– if I could establish a style, which would be a child-like simplifying of each object into design, peasantish decorative motifs, perhaps I could become one of the little people who draws a rose here, a snowflake there, to stick in the middle of a story to break the continuous mat of print; they print everything from wastebaskets to city-street scenes…”

Plath’s description of her sketching style could be applied to my own notebooks. Ask any acquaintance of mine and they will tell you that I am an ever-doodler, that my hand-flesh has practically grown around my pen, that anyone in my view is vulnerable to become a subject of my drawings. Like Plath, my drawings are based in observation but with the surrealistic twist of my inner musings.

Although I am enrolled in a writing MFA program, I spend more of my time making art, and to me these two mediums are inextricably linked. Drawing for me, as it was for Plath, is always a pleasure. Art, in her words, brought “a sense of peace to draw; more than prayer, walks, anything. I can lose myself completely in the line.” While my process of writing is fraught with self-doubt and social pressure, drawing simply feels right. I have never read such joy and Pride in Plath’s prose as in a letter to her mother in 1956 about the publication of her “Sketchbook of a Spanish Summer” in the Christian Science Monitor. One can imagine her bouncing in her seat as she wrote about “the four of the best sketches in pen-and-ink I’ve ever done… [they] will amaze you… [they] are very important to me.” This book finally brings to light an element of her life that was essential to her happiness.

After reading the letters contained in this book and spending some time with her sketches, I am convinced that Plath has come to haunt me. Her restless ghost has traveled to the heart of the midwest to nag me to pick up where she left off, to pursue her peculiar ambition to publish little black-and-white drawings in The New Yorker. She set aside these early artistic dreams to focus on her poetry, and due to unfortunate circumstances was unable to carry through. Even before this book landed in my lap in time for a Valentine’s haunting, I have been conflicted about being in a writing program for fear that I might have to push my drawings to the back burner. This book, or perhaps Plath’s ghost, has convinced me to be stubborn– to weave together my drawings and poetry, to publish art and text in tandem.

Frances Cannon is currently an MFA candidate in nonfiction creative writing and book arts at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop at the University of Iowa. She is also working as an editorial assistant for The Iowa Review and a freelance writer for Little Village magazine. She has worked in editorial and design for The Lucky Peach journal of food writing, The Believer, McSweeney’s Publishing, Seven Days newspaper, Taproot magazine, The Art of Eating, Vantage Point art and literary journal, The Salon art and literary journal, and Thread magazine. She has studied poetry, fiction, nonfiction writing, and many mediums of visual art: relief printmaking, drawing, painting, woodworking, silkscreening, etching, and photography. She can be found online at francescannon.wordpress.com.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.