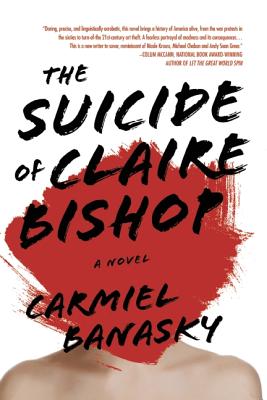

We’re pleased to have an excerpt up from Carmiel Banasky’s forthcoming novel The Suicide of Claire Bishop, due out next week on Dzanc Books. In a recent interview for The Rumpus, Banasky said that “[m]y novel is equally about madness and the fear of madness. So what that meant was presenting schizophrenia as a relatable experience, without reducing or romanticizing it.” Juxtaposing narratives set in multiple decades with observations on art and obsession, Banasky’s novel covers a number of haunting themes.

The Thaw

Ovid, New York, 1982

She moved up there in winter so she never saw the ground. Covered in snow, December to May—the house she grew up in, and yet she couldn’t remember the land it stood on. There was a garden that must have been beautiful once, a low fence around it for the deer and pie tins tied there with twine, clacking in the wind. The woods behind and tracks from animals she never saw. Footprints, every morning a new pair circling the house and never once a glimpse of the thing they belonged to.

And above it all was a low, constant rumble, like something was always hungry. Snow slow-grinding into itself.

She fell, somehow, into the habit of calling her mother by her first name, Elsa. It felt appropriate—Elsa—since they hadn’t seen each other in a decade. And since her mother was a different person now. Her mother’s breasts seemed to have vanished. This was the first difference Claire noticed. She’d had such a nice body; Claire remembered being jealous of it once.

As soon as she walked into Elsa’s room in the morning, she knew she was late. It was the second Tuesday in January. She’d been there two weeks and still she hadn’t learned.

Elsa was sitting up against the headboard, watching the door. Her legs were straight, wrapped and weighed with many blankets. They looked separated from her torso, like pieces of a child’s toy detached from its plastic body. She looked at Claire expectantly, waiting, it seemed, for Claire to make the first move. Claire inched timidly toward the lumps of Elsa’s covered feet; they made her think of animals under snow.

A hand moved. Claire saw it travel toward the nightstand, the alarm clock. She saw what was going to happen before it happened, and yet had no power to stop it, not even to lift an arm to shield herself. Elsa grabbed the clock and pulled her arm back, fluid as a ball player, as if the motion were practiced. The shining metal arced across the room. Hit Claire in the forearm hard. Clanged to the floor. The metal bell cried out once.

Slowly, Claire looked at her arm. A small scrape, no blood, but it would bruise. She wouldn’t yell. She walked to the bed and pulled the covers back. Throwing the clock seemed, to Claire, like something Elsa had always been capable of and would have done many times over if she’d ever given herself permission. The only difference now was that Elsa had stopped arguing with herself.

“You have good aim,” Claire said.

“I’m hungry,” Elsa said. “Stop dawdling.”

Elsa still knew Claire, but sometimes she only seemed to know her. And for the trust Elsa put in her—a trust that was evident despite the throwing of alarm clocks, even if Elsa had little choice in the matter—Claire felt grateful, privileged even. But, on occasions like this, when Elsa revealed her aggression, that trust felt manipulative, as if Elsa were only feigning obedience while planning her secret escape. The house was a prison, and Claire the warden.

The nurse had said not to take these acts personally, to find the immediate cause and change the focus. But what if the alarm clock was an act of revenge?

Now the focus was on dressing. Elsa’s nightgown rode up above her knees, which were pale and brittle. Elsa was all knees. Claire helped her slide to the edge of the bed, lower her legs, put on her slippers. She laid out two cotton shirts—one blue, one white—and asked, which one? After five minutes deliberating, Elsa chose “the blue, natürlich,” over the white. Claire set each item of clothing on the bed in the order that Elsa was to put them on, then pretended to be busy organizing the bureau while her mother dressed. It didn’t matter if something was on backward or if dressing took half an hour, Elsa was to do it herself.

Each day began with berries and sour, dry yogurt. Each morning, Claire carefully set the table, which Elsa had taken to calling the bed. The long wooden table her father had made—a reject commission he’d brought home from the shop. He was always disappointed by his work, which Claire could find no flaw in. She loved running her hand over the wood—Birdseye Maple—slick from touch, but old and deeply grooved, stories of meals buried in its wrinkles.

Each day the berries, every morning the sleeping trees in the yard. Trees so dead they were alive, with brittle twigs like bunches of blooming flowers. Their window reflections leaned over Claire as she prepared breakfast, reminding her of her own winter body. Claire saw her morning-self setting the table. She saw her dry winter hands, the stealthy veins beginning to rise from her skin like waves, the new texture of age, laying down the shallow bowl and thick plastic plate. It made a hollow noise on the wood.

Elsa stared blankly into her floral-patterned bowl of yogurt and berries. Claire watched her dip her spoon gingerly into it, nearly coming up empty.

“What’s the matter? You don’t want it?”

Elsa scowled at her. “I am hungry. I said this already.”

“This is what you like. You like blueberries.”

“I cannot have this,” Elsa said, pushing it away.

“I’ll get you something else.” Claire tried not to sound exasperated. She was about to dump the food in the garbage when she saw she’d forgotten yet another rule: how difficult it was for Elsa to see food on any patterned bowl.

Elsa was too proud to admit, or simply couldn’t articulate, that she needed help understanding breakfast. Each day, Claire added a new item to her own list of failures.

Claire transferred the yogurt to a solid blue bowl, then sat beside Elsa, watching the slow procedure of spoon to mouth, wondering when her mother would forget how to swallow.

After breakfast, in front of the fire in the living room, Claire would read the local paper out loud if it seemed Elsa was interested. First the feature pieces, then the weather. Elsa would listen calmly, staring into the fire. Sometimes, in her more lucid moments, she would interject with a criticism. In the middle of an article about the recession, Elsa said, “I don’t like this one. I prefer the one you read yesterday. Read it again.”

“It’s in the bin already,” said Claire.

“I liked it better when he talked about Reagan. I know you worked for Carter. You look guilty. Good thing they didn’t shoot Reagan with better bullets, otherwise we would have lost—” Elsa faltered, searching.

“Another president?” Claire tried.

“Otherwise, we would have lost a great man.”

Claire leaned over the arm of Elsa’s chair to show her a photo of Jeremy Wendell, a man of the community who was found in the late January snow, stuck under his garden fence where he’d had a stroke. Elsa laughed strangely.

“That’s not nice,” Claire said, pulling the paper away. “He’s dying.”

Elsa nodded and laughed again.

Claire had assumed that by a month in she’d be jabbering to herself with cabin fever. Instead, she became more self-conscious of her language, second-guessing every verb and preposition she used with Elsa. Was it “than” or “then?” Did she pronounce the word “prerogative” correctly?

It was the prerogative of elected officials to propose cuts to the federal budget and announce a ninety-one billion dollar deficit on Monday. On Wednesday, the “freeway killer” was convicted. Then, in a town just down the road, thousands of gallons of radioactive water were released into the drainage system and radioactive steam into the atmosphere when a tube burst at the local nuclear power plant, no danger to the public!

Again, Elsa laughed.

Midmorning, Claire would leave Elsa with the TV and the dying fire to go outside and chop wood. The ax—leaning against the house like some bent and broken man—was brought out to an upright log resting in the snow. Her father had taught her to chop wood when she was six years old.

She arched her lower back, tried to let the cold numb the ache crawling up from her femur. She bent her knees, touched the cold raw-metal tip with her bowed forefinger, swung up and around like the arc of the sun. That’s how he’d taught her—he said she was the earth and the ax-head the sun. She’d corrected him—and was sorry for it later—saying that what he meant was the ax was our perception of the sun. That if he thought about it, the ax-head was the earth and he was the sun, pulling it in orbit.

Breaking something to pieces, breaking through the wood, destroying its shape into usefulness. It was a muscle memory that had never left, not in the forty-some years since she’d last lifted an ax. Her hips ached—yet another joint she’d taken for granted until it troubled her. But for a moment, she felt strong. Falling on something with all her weight in one unified motion, every ounce of strength needed to get the clean cut. She hadn’t felt this sensation in years, hadn’t known it was something she missed, desired. This was it, this was all there was. Engaging with the world, fixing on a task, finishing it. She felt her father in the swing.

She brought the logs inside and put them by the fire, under the old bread oven, to dry. And she could smell him dripping and drying after he came in from the cold. Her father smelled like thawing wood. He must have sat here on the couch, where Claire sat now. He must have held her mother’s hands in both of his.

They said he called the ambulance himself while it was happening, his heart attack—he didn’t want to burden Elsa. He took care of her for more than a year before he passed, two months ago, and he’d never told Claire about Elsa’s disease.

It was time for Elsa’s midday medicine but Claire didn’t feel like moving her body. She felt Elsa’s stare on the side of her face just as she felt the flames from the fireplace in front of her, indifferent and hot. Claire could tell Elsa was getting ready to speak from the rough word-searching noise she made with her jaw.

“I’ve got to get ready.”

“Ready for what?” Claire asked lazily.

There was a long pause. It seemed, for Elsa, that each word was a great search, always starting at the beginning of an internal dictionary. Elsa said slowly in her sand-voice, “We’re going to celebrate. We’re going to the theater.”

The fire crackled and ticked, keeping time.

“We are?” Claire said, turning to her now.

“Not you. Me and Ernest.”

She said his name as if he were alive. “How old are you?” Claire asked calmly. Locate her in time, the nurse had said. Pull her back. Or not.

Elsa said, smiling, “Fifty-four. Ernest says I look thirty-nine.” She reached for the box of tissues on the arm of the chair and began pulling them out and ripping them in half, one by one. Paper dust floated around her.

Claire took the box away gently. “Why don’t you fold your towels?” she said, grabbing the stack of clean washcloths from the coffee table.

Elsa shook her head. “I don’t have time. I must get ready.” She still held half a tissue tightly in her hand.

What would her father have done? Had he fueled Elsa’s delusions and entered the past with her, or corrected her and said no, here we are, old and still in love? At fifty-four, what would they have been celebrating? Perhaps that was when Elsa and Claire’s father had finally bought the land they’d always rented. Thirty years ago—long after Claire had left. What had she been doing at that time? Something she was indifferent about, surely, in the city with Freddie.

“Were you celebrating the house?” Claire asked.

It made perfect sense that Elsa would not return to a year when Claire lived there, when they were struggling with money. Who would choose to go back to that?

“He’ll expect me to be ready at six,” Elsa said more confidently. “I have to get dressed. The new production opens at the theater tonight.”

Still—there was a movement inside, some small, buried thrill. A lightness in Claire residing right beside the hurt. She wanted to indulge this delusion. She was almost giddy about it; they could do whatever they wanted. And they were going to have a good time at it if it killed them.

“Let’s get you ready then, hurry up,” Claire said. She helped her mother out of her chair and into the bedroom. A painful giddiness in her chest. Desperate, suddenly, to help Elsa stay inside that day she remembered so earnestly. Was there salvation there, if she could help her mother live in a pleasant memory?

She left Elsa standing in the center of the bedroom and went to the closet, which no longer had doors—another story of the house that she would never know. She knew just what dress, one she’d seen Elsa wear ages ago. And she knew it would still be there. Elsa never threw away clothes, preferring instead to alter and patch forever. Claire slipped it from its hanger. The navy blue dress gave up soft buds of dust.

It was easy enough to slip off Elsa’s quilted bathrobe with the zipper down the front, but quite another to force her arms into the meshy fabric, a half-tissue still wadded in her clenched fist. Elsa’s skin was clammy and the transparent sleeves clung to her shoulders. The back zipper got stuck on Elsa’s underwear. Claire thought she heard her whimper but she couldn’t be sure. This was what Elsa wanted, to time travel within her own life. Claire was only giving Elsa what she wanted.

She sat her mother down on the edge of the bed and brought a dusty makeup bag from the dresser. Elsa had been silent since the living room.

“Tell me what play you’re going to see,” Claire said.

“It’s a play,” she said.

It was harder than Claire thought to apply lipstick to someone else, clumpy where the skin was dry. It didn’t look good.

“I’ll put a blue-gray eye shadow on you. To go with your dress.” Claire showed her.

But Elsa wouldn’t keep her eyes closed and some powder got in them. She kept blinking and rubbing her eyes so the makeup smeared into her temples. Claire caught her hand before she could make more of a mess.

“Where are your dinner reservations?” Claire asked.

But Elsa was distracted by something over Claire’s shoulder. She touched Elsa’s face to focus her attention, but Elsa wouldn’t look her in the eyes.

Claire stood up and looked dramatically at her empty wrist. “Come on or you’ll be late. Don’t you know you look beautiful?” She smoothed Elsa’s coarse white curls down with her palm. Her hair was a handful of twigs.

But she did look beautiful if a little haphazard. Claire stood her in front of the mirror. “See? You’re beautiful.” Claire used a thumb to wipe away the excess eyeshadow, then pried open Elsa’s fingers and placed the torn tissue between her lips. “Press down,” Claire said, and Elsa pressed down. Elsa would let her do anything. It was like dressing up a doll. Claire looked at her mother’s stooped body in the mirror, how much smaller it was than her own.

Elsa stood there, shivering in the warm bedroom. “Ernest will be underdressed as always,” she said, nodding at her reflection. “I’m ready.”

Elsa shuffled out to the living room and down the hall, slowly, each step as precarious and difficult to land on as words. She stopped at the front door. She did not open it.

Now what? “We’ll wait here?” Claire asked.

“He’s late. Again.” Elsa pressed her head to the high window in the door, which she just barely reached, swiveling her forehead left then right, following the snowy road. She tried lifting herself to be as tall as she actually was, but her body wouldn’t unbend.

And Claire did nothing. She stood behind her mother, watching her wait, waiting for her to forget what she was waiting for. What had she done? Fairly pushed Elsa into the past and for what? To watch her wait for a dead man? When would it hurt least to be pulled back?

But when Elsa answered these questions herself by saying, “Put on the Marlene Dietrich, please,” Claire found she did not want to. They hadn’t finished the memory yet. Claire wanted to know what happened next.

“Don’t you want to go to the theater?” Claire heard herself saying.

Elsa tried to turn back toward the living room, but Claire spun her to face the door again. She shushed her, though Elsa hadn’t made a sound. Claire held Elsa upright, as if she couldn’t stand on her own. You try to keep a moment that’s not yours to keep.

“Let’s wait here a moment longer,” Claire said, “I think I hear a car coming.” Was she trying to conjure her father back from the dead? But Elsa wouldn’t give her a moment longer and in the struggle, with Claire pointing at the window with one hand and holding her mother up with the other, Elsa yelped and her knees buckled and she was suddenly on the floor, yelling in German in her navy blue dress.

Claire tried to help her up, but Elsa was dead weight. “Stand up, please.”

She wouldn’t stand. Elsa looked like she was about to cry, but instead Claire found her own face was wet. She had missed the moment of release and there she was crying and she couldn’t stop. “I’m sorry. Please, Mom, you have to get up.”

To know her mother as she was now, the way she’d never know her father—to know how her knees locked together when she stood, how she shuffled her feet when she couldn’t find the words. How her far-off smile was slightly raised on the right side and how she wanted to hear the same song over and over again. And how they shared a loss of memory, sometimes: Claire couldn’t remember how her father took his coffee. Or how he’d said goodnight to her at bedtime. What stories he told, or didn’t.

“Put on the Dietrich,” Elsa said, calmly.

Lifting her slowly, Claire brought Elsa back to the living room, sat her in the big chair. She dropped the needle on the record Elsa wanted, which never left the turntable. The phonograph crackled then gave way to Marlene Dietrich’s voice singing in German, Where Have All the Flowers Gone.

Perhaps Claire’s father was held late at the shop, or whatever job he had then, but had arrived home just in time—Claire imagined them rushing to their seats in the theater, the rain in their hair catching the light of the chandelier. Or maybe nothing happened next. Maybe Elsa was left waiting in her navy blue dress, watching for him out the window, watching the cold move, and he failed to come home. Perhaps her mother was waiting for him still. The mind drifts to loss.

***

May 19, 1946, Ovid, New York

Claire finally visited yesterday. We were expecting her weeks ago. We were, in fact, expecting her for years, but that is another matter. She gave me a kiss on either cheek, because that is what the Europeans do, she said. She must have read this in a magazine. She did not embrace me. I was so upset I went to my room and said I did not feel well. Later, she wanted to go to the grocer, to get some exotic ingredients she had learned to cook from her new city friends, though she assures me she does not live in the city. She and Ernest made a plan for the three of us, though they didn’t consult me, to have a fancy dinner and pretend we were at a restaurant on the Riviera or somewhere. But I put my foot down and said I did not want her going to the store with me.

She wrote me a grocery list: artichoke, hearts of palm, mango, avocado, swordfish. We were alone in the kitchen. I said I did not think they would have those items. She asked me about her grandmother. I told her she had died of pneumonia several months ago and if she’d come home a little sooner, she might have said goodbye. I only told her the truth. She made as if to hit me. But I caught her arm before she could, and I slapped her face. It hurt my palm, I was surprised at that. I had never hit her before. She ran from the room crying. I thought, yes she is acting her age now, rather than the age she thinks she is.

A woman at the store, she is Italian, has always had eyes for Ernest. She asked after him. I called her a whore under my breath but she did not hear me. I am afraid I have it in me to kill a person who would take something that is mine. But Ernest has eyes for no one aside from me and Marlene Dietrich. And even for her, only ears. She is good company to keep, and I tell him that I would leave me for her as well if I had the chance. I bought the foods Claire has always liked. I made her favorite dinner—breaded schnitzel and cheese noodles. She ate as if it pained her. Only then did I think to ask about her husband. I had forgotten him. He was busy with work, she said, and could not visit but sends his love. I thought, he is afraid of us. She refused to speak of her house or new town, when Ernest asked. I was glad. I did not want to hear those stories.

I have made up my mind to not be kind to Claire as Ernest is. She must know how much she has hurt us, and he will never tell her. He is too kind. He opens his arms and his heart and she throws rocks and spits at him. I think of when Ernest bought me a box of watercolor paints for my birthday. I asked for them, but I believe he would have known to buy them anyway. Claire was a baby then. I was stupid and left them on the floor for only a minute while I went to the toilet. Claire got her fingers in them and ate them. She smiled and laughed. She did not think they tasted bad. I was tempted to taste them myself, her pleasure was so great. Then I thought perhaps she was poisoned and it was having a stupefying affect on her, so I stuck my finger in her mouth and it came up blue and she thought this was very funny until she started to cry. I did not know what I was doing. I remember thinking, what if Ernest were to come home and find Claire poisoned by paint? I was sure he would leave me. That was what I thought. I did not think, what if my baby dies? I did not know what I was doing with a baby. Perhaps I also thought: if she does die, maybe we will have enough money to survive. I was only twenty years old. I was unqualified. Still, I am unqualified yet cannot be fired or quit.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.