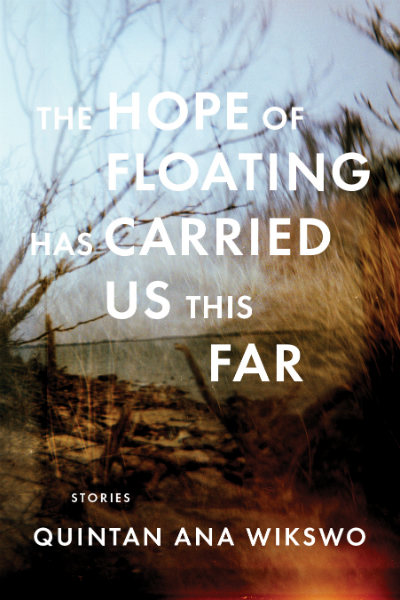

Inside the work of Quintan Ana Wikswo’s The Hope of Floating Has Carried Us This Far.

* * *

Dear Friend,

First, I received an electronic version of your book. Then a hardcopy version arrived on the doorstep of this far-flung outpost. Then another hardcopy. And then another. They began piling up on my stoop like volcanic ash.

It felt good on the palm. That was the first thing I noticed. Then, as I began to read, I wondered, what kind of reader have you created? Will you be able to keep them on dry land? Will the shapes of their bodies slowly evolve over time? What about their concept of color? Will light finally refuse their forms and release them into the realm of hunger and longing?

During the winter solstice, I would have to use a pickaxe to break through the crust of ice formed on the lake. As I held her beneath the surface, the handle of the butterfly net would form complex crystals of frost. Delicate, as though it were trying to tell me something in a code of its own sharp language. My mittens would leave a pelt of wool along its surface, softening it. Each winter I worried that my mother, too, would freeze, and not fit back into the jar after I pulled her out. But this never happened.

* * *

Like love, writing is a convergence of birds. I took your book overseas with me. Here, I found myself wrestling with demons and huddling under airborne contaminants. The location was tropical. My voice was constantly shaking. I had dreams in which I existed in alternate realities that were filled with melancholy and draped in the light of unwell, yellow moons.

One moon crossed over the path of another only to create debris. Another moon rubbed and rubbed and rubbed itself on the nearest frictive surface, in the hopes of catching fire. Still another wasn’t a moon at all, but the outline of a familiar face from a very distant past.

Even the local children knew why birds would not land on the tower balustrades. Why the floorboards had been painted and why the cracks so very carefully filled in. Why the aloe grew quickly along lines of nonexistent pathways, and why the lizards refused to cross into those furrows.

* * *

Your book occupies two fusional states. One of these states is gravity resistant and exudes protective properties. It draws us in. The other state comes quickly and allows us to dissolve into thin air.

Whenever the gate opens, the crowd thickens and thins. It clots and coalesces around itself with vascular anticipation. One pilot rushes forward – Is it her? Is she here at last? Did she finally die?

* * *

It is rare to gain access to the constellation factory in time to watch new stars be minted. It is impossible to proceed through these passages without feeling the gravitational tug of longing, an aching attraction between two continuously opposed forces. One of the narrators here is translucent and deliberately obscures their gender. Another narrator dares you to question the merit of a different alphabet. Still another narrator isn’t a narrator at all, but a creature of unknown origin whose existence is only possible when the reader stands ankle deep in pinkish water.

This is our hour. There is no magic for women in the morning – all is preparing, inventory, reminders, making ready for tasks, errands, disasters of blood and body and book learning. Clothing bought and sold, sizes adjusted for age, accounting for nutrition. List-making, stocktaking, coals in the oven, and where are the pencils to be sharpened? The knives. Brisket. When will the butcher be ready. For us, the afternoon, the hour of naps.

* * *

Let it be said, I dragged my fingers through the remnants of a fire so that I could impart its ashes on the pages of this book. I’ve smudged ash all over the pages in an attempt to let organic matter collaborate.

Let it be said, the words in question dislodge liquid from salt and motivate us to form a cabal. Some of us tear posters down. Others pause, simply hoping to remember where we started.

When she writes to me as she did before, at first there is the incomprehensible sound of crickets, and then there is my familiar smell, a scent released from my pores as dark and full of longing as they were before.

* * *

Then, as if that wasn’t enough, you describe a specific color in great detail, but without all the usual visual clues. Perhaps the color you describe is called disturbingly terrine or perhaps it is called perspectival autumn.

* * *

I’ve never read Bowen. I’ve never read Perec. Or Lyn Hejinian. I’ve never had Lispector tell me about strawberry season. I’ve never created brackets of text this satisfying. I’ve never hurtled through the wide arms of intimacy that align the produced artifact and the feelings the artifact evokes.

It’s probably about time I revealed a few more details: I do live near a volcano. I am afraid it will erupt.

Anger springs from love. Absence from overcrowding. Asphyxiation seems like a good way to go. But then, some say the same thing about becoming biodegradable. This is why the moon is off-limits. The only other thing I’ve ever asked for is that we become case sensitive.

Each story relies on a delicate juxtaposition of image and text. It supports the manner in which we process white space, as a sort of separate, “meta” narrative. Paragraphs seem unnecessary here, as if each sentence is a shaman holy enough to regard the stanza as a pair of shackles, or a superfluous control mechanism.

When the letters began to arrive, I had been home for nearly six months.

I found I had no memory of writing them.

I barely recognized this woman, their writer.

Despite all claims of dry, hers is a damp heart, and pounding.

As time passed, I remembered her less and less, yet knew her more and more.

* * *

Dear Writer, Your text is written in braille and your performance of the text takes place in a cage, underwater. You have instructed the driver of the boat to chum the water furiously in order to attract predators. You have instructed the camera crew to dip their cameras into the water using long metal poles. You have pulled a few of us up from nothing:

Most contemporary scholars posit that across time, older, long-extinguished shadows of ourselves cut and clawed and hewed this refuge, then polished it, abandoned it, and moved on.

Others suggest that early human life-forms developed a primitive technique for mining a soft substance from the earth, and these coiled and tilted tunnels were canals for its extraction.

The folktales say that once, very long ago, two sea creatures came into being deep below the Baltic Sea. They grew alongside one another, twisting and turning ever outward together in a meticulous southward calculus of movement.

* * *

There are some among us who still eat meat. There are others who still reach for illusive metaphors.

Dear Reader,

I know you.

I know where you came from.

I know how you got here.

I know how to find you.

To feel you are at all times in error.

To turn back. To retrace your steps. To seek decreasing distance from the point of her. To become dizzy and lose consciousness from lack of air and light and heat.

To take off all your clothes and lie there, crying.

Believe that she does not exist. That you have become a madman.

And then arrive at that point, at the binding site, and find her there.

* * *

Lastly, let me translate a passage for you.

Test pilots drive old-fashioned cars. Ducklings are friskily entrenched and accessorized. Drowning is just another form of nearly-realized dystopia. Hemorrhage: A feeling that is not so strong. Oxygen is recursive and relies on the gentle pairing of sage and huckleberry. Pyongyang is the place where you make things happen. Skulls are the implements we use to make the place dark. Hairdryers are both the means and the end. Licorice is neither. Fracture = power. Death = comedy. Braids connect us to the world. The rain forms the words that let us in.

She was going for a test at the doctor. The test pilot drowned still strapped into the cockpit. Her hairdryer shorted out. Ducklings. Hemorrhage. I had rewired the house. The pilot’s cause of death was asphyxiation. The oxygen useless. She braided her hair the way I loved. She smelled of chamomile and licorice. She wore galoshes in Pyongyang in the rain. My skull was fractured.

Notes on Methodology:

The Cochlea is coiled, ready to strike. It is prehistoric and represents our clearest physiological link from the Cretaceous and Mesolithic periods. Back then, our snail shells were more suited to their estuarine environments. Our aphasia was more entrenched; its affects harder to shake.

My initial vision for a response to this book was to produce a sort of collaborative/interview piece with the author. This response would be one in which, the three of us (book, author, reviewer) developed a series of texts meant to be evocative prompts. Eventually however, I simply began to imagine that, like me, the reader of this book would also desire to lose their balance; to deliriously trip over their own feet. It was in this collaborative spirit that I proceeded, in the hopes that, together we (the three of us) might be able to divine wind direction and capture illusive spirits.

Craig Foltz is a writer and multimedia artist whose work has appeared in numerous journals including Fence, Diagram, and Faultline among others. A book of poetry and a collection of fiction are both available from Ugly Duckling Presse. He lives and works in New Zealand, on the slopes of a (theoretically) dormant volcano. More here.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.