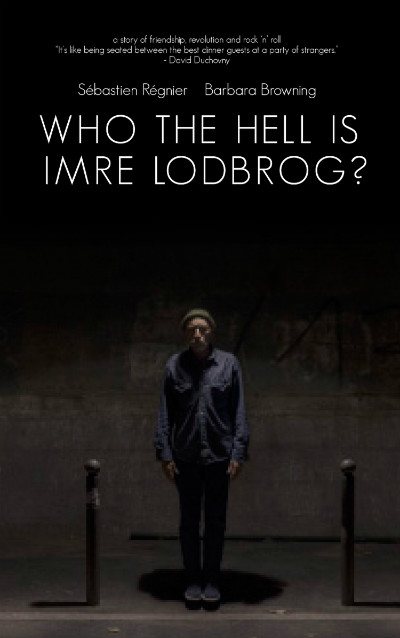

We’re pleased to be publishing an excerpt from Barbara Browning and Sébastien Régnier’s new collaborative book, Who the Hell is Imre Lodbrog? It’s an exploration of art and music, perception and revolution, told through two distinct voices. The book’s New York launch will take place tonight at Dixon Place.

***

Imre Lodbrog was born in July 2008, with a hangover and on the road between Cherbourg and Evreux. He wasn’t a newborn babe. He had fifty-six years under his belt.

I was on my way back from seeing Freddy. But was that really Freddy? His enigmatic words the night before, as he’d stared at me with a slight walleyed look, still shook me to the core: “The guy who’s speaking to you at this moment, Seb, is not me…” In the course of my visit, Freddy urged me to change my name. Or at least to adopt a new one for the rock ‘n’ roll adventures that awaited us. A new name? To give birth to a new me? The idea might be interesting, but… What name?

Sometime around the year 800, a more or less mythic Viking king was thrown into a swarming pit of vipers to meet his end: Ragnar Lodbrog. Such a death could only lead to the birth of a legend… My father had the firm conviction that our family name, Régnier, was derived from Ragnar, our Norman origins erasing all doubt.

In another time, somewhere in Transylvania, my mother’s father was called Imre. She was two years old when she lost him. According to my mother and a few other rare testimonies, he was a wise man, a patriarch, the solid trunk of a family tree with wide branches – today reduced to almost nothing.

At kilometer 244, the collage came together on its own: Imre Lodbrog. It seemed obvious. The idea that it was practically unpronounceable and hard to remember pleased me in equal proportion. I stepped on the accelerator.

So, my real name is Sébastien Régnier. And for Sébastien Régnier, the twenty-first century had begun well enough. After fifty years of Parisian life, I’d thrown in the towel and moved to the country. With my longtime companion Atika, I had a six-year-old daughter, Lucie. Often, the roles of children and their parents are reversed. The good we want to do them returns to us like a boomerang. At the end of the summer of ’99, which is to say at the end of the school holiday, we discover Lucie crying in a corner. We’re on vacation in the south of France. When we ask her what’s wrong, she tells us, “I don’t want to go back to Paris!”

That’s the straw that breaks the camel’s back. Suddenly I can’t even imagine her growing up in the unhealthy gloom of the capital. We promise Lucie that before her next school vacation, we’ll be living in the country.

I will always love Paris. But in the past few decades, Paris has changed a lot. The air is charged with an ambient nervousness, and often agressivity. And gone is the time of cheap little pleasures, like sitting at an outdoor café over a coffee, watching the passersby. Life has gotten impossibly expensive. The population has gentrified, and the good old neighborhoods like Belleville or Ménilemont have crumbled like sand castles. When I think of my youth, it’s like another city, another epoch, another film.

In June of 2000, we leave Paris for Pourry, a picturesque little hamlet (whose name, ironically, sounds like “rotten” in French), with about two hundred inhabitants, on the edge of a forest. For a pittance, we buy an old Norman country house. The city rat has turned into a country mouse, finally realizing a childhood dream: we have a few chickens, rabbits, cats, ferrets, and a dog. In fact, the king of dogs: we name him Ragnar – as in that Viking myth that already looms over this story.

A period of true happiness. The arc of the sky is 360°, I rediscover the seasons, the ellipse of the sun, the evolution of the moon, everything smells good – the hay in the summer and the wood smoke in the winter. And what’s more, however much you may sympathize with Karl Marx, being a property owner isn’t nothing. I remember the voluptuous sense of pissing, for the first time, under the stars in MY garden.

One spring morning, in 2002, finally having given in to Atika’s insistence, I become a father for the fourth and final time. Anouk arrives. A baby owl we found in the forest comes to complete our bestiary, and it becomes Anouk’s guardian angel, perched on the frame of her cradle, scrutinizing with its round eye this strange little creature. As for work, I have nothing to complain about: one film’s just come out, and I’m writing another.

But in 2004, the machine goes off its rails. My father dies – in my arms. I seem to box up the shock of an event I’ve dreaded all my life. One says that great pains are silent. They’re also subterranean. They march through our galleries like termites, crumbling our structures as they go. My notion of time has always been a little hazy, maybe because time and I have never truly been friends. Too short, too fast, too… And not enough. But beginning in 2004, and for several years, time really becomes a formless mass in which all my guideposts sink, except for the alternation of the days and the nights. Christmas seems to come back every two months.

What’s more, my relationship is on the rocks. After the enchantment of the first few months, disillusionment strikes Atika: isolation, discomfort, the animals that shit all around us, the mud we track in on the soles of our shoes… She misses everything about Paris, the pleasures, her work. Me, I won’t budge, and anyway, it’s too late. If it was hard to leave Paris, going back is practically impossible. So, I begin to look like some sort of jailer in a confinement I thought we’d chosen together. And finally: no more income is in view: the day arrives when I deposit our last check, The specter of material difficulty returns. I should have been used to it, but this time, it was one time too many.

When I was ten years old, at the Porte de Montreuil, a fucking gypsy grabbed my hand to read my future. After which, she pronounced her prognosis: she traced in the air a chain of mountains, with crests and valleys, highs and lows, explaining: “Your life will be like that!” She saw right. My life has never had a head or a tail. Blown by the wind here and there, passing from calm to storm, from inertia to chaos, from here to there, from solitude to multitude, from hardship to provisional ease, from high to low and low to high without any precise direction or a clear cause and effect, except for those provoked by pseudo-chance. Everything in the name of a wild and innate dread of an “ordinary life,” with La Fontaine’s fable “The Dog and the Wolf” as my guiding principle:

“You live on a leash?,” said the wolf. “You don’t run free wherever you want?”

“Not always, but does it matter?”

“It matters so much…”

Grosso modo, a sort of enslavement to liberty. But having arrived midway between fifty and sixty, I’d suddenly had my fill of, as we say, holding the devil by the tail – being tossed around by fate, on a precarious loop. All that made for a rather bitter brew, and instead of facing the facts, I put my head in the sand.

That year in Pourry after Atika left, the cannabis plants I’ve been cultivating give a remarkable harvest, supercharged with THC. Enough to fill two garbage bags. I consume them almost all by myself between the fall and the spring. Let’s just say it is a smoky winter. Well, smoke and depression make a nice little team: one accelerates the other, which makes one want more. It can seem like you’re protecting oneself and when in fact you’re drowning. Same goes for alcohol. But the biggest error, without a doubt, was abandoning music, the guitar, my songs. Since the age of fifteen, I’d written more than two thousand songs. Aside from two or three little televised eccentricities, they hadn’t done anything for me – and I hadn’t done anything for them. That garden had never produced anything but wilted flowers. It was time to hit the brakes. My guitar had been sleeping in its case, and my dreams of music slept with it. As for travels, which had always provided both the tempo and the color of my life, they’d been packed up with the suitcases on the top shelf of my closet. Elsewhere had definitively gone back to being elsewhere.

That’s when I begin dragging myself through the gloom, with my little Anouk as a sole ray of sunshine. She accompanies me (along with Ragnar) on my walks in the forest whatever the weather. “Storms give you courage!” was one of her first sentences. I occupied myself with the construction of a little tent in which we spent some enchanted nights.

But each morning becomes an ever murkier swamp to cross. What good is it putting one foot in front of the other, letting the days add up? After all, I tell myself, maybe I’ve had my run. My life has been rich in all kinds of experiences, dense in extravagances, just like I’ve wanted it, at the cost of any strategy for security, and I hardly wanted to vegetate my way to the cemetery. What can I hope for now? A new life, a new love, new travels, a resurrection? Reality is right there in the mirror, where my face is turning into a crumpled dishrag. I was seeing the face of my grandfather looking at me.

A little parenthesis: over there, wherever he is, my father keeps sending me signs. In life, he had a habit of writing down phrases, thoughts, quotations, on little scraps of paper that he left here and there among the pages of his books. Since he left, I’ve often found these bits of paper. One of those sad mornings in Pourry, I find the following words in his hand, seemingly posed there in the night, a quotation from Bergson:

“The future is there. It calls us, or rather pulls us toward it. That uninterrupted traction that makes us advance down our path is also a continual cause of our action.”

A motor to the future? It left me thinking…

One day, Danielle, a dear old friend, sees me and says, “Have you looked at yourself in the mirror lately?!” She presses me to get some treatment for depression ASAP. She’s been through that herself… A shrink confirms it. Insomniac, undernourished, I’ve waited far too long, it seems, and my condition is diagnosed as Major Depression.

Me? Depressed? Impossible! I had so many friends who had suffered from that condition, some to the point of ending it all, and I’d always tried to support them as best I could, thinking myself invincible. The confirmation of the diagnosis, with a big old prescription for antidepressants to boot, just makes me more depressed. With Atika, this really announces the beginning of the end. Mired in my own descent, I’m barely balancing on a high wire stretched over an abyss.

Our social universe doesn’t help much. In our world of winners, it’s no good to lose. So it’s a sublime irony that, a few years later, the kind of losers extends his hand. Frédérique Tchékovitch, AKA Freddy.

Coming back from his place in Cherbourg, in 2008, I took his advice and created this salutary schizophrenia. There would be, on the one side, Sébastien Régnier, screenwriter on the decline, and on the other, Imre Lodbrog, a newborn phantom to whom I’d give body and soul. A sort of liberation. As if a pseudonym would be enough. As if changing names were the same as changing skins.

Thanks to Freddy, I take my guitars out of their cases and get back to work on my songs – but this time the tone has changed. No more sad little balads: I have The Stones in my head and I’m spitting venom. My voice has also changed. And my look. In short, I’ve molted. As Lodbrog now, I would turn my black years into electric fuel.

My old friend Gregory, intrigued by this Lodbrog concept, makes a couple video clips where my clone appears on YouTube in his war gear: a Stetson, a pair of dark glasses, and a sullen mug. A while later, around the beginning of 2013, I think, this same Gregory suggests that I put my songs on SoundCloud, a site with an aerian name where musicians from all over the world – mostly amateurs – post their work just for the pleasure of sharing it. After a few weeks, I find myself with about a dozen “followers.” Pretty quickly, I pass from twelve to fifty, a hundred, a hundred and fifty… Somebody’s listening to me on all five continents. A new form of anonymity, but also, a sort of pleasing form of recognition.

I’ve always frequented record stores, kept up on what was coming out—an addicted musicophage—until the stores all started closing. Now, on SoundCloud, I rediscover the pleasure of discovery. Some real artists are hiding out there, one just has to look for them in the hodgepodge, from electronica to the blues, from pseudo-classical to rock … One day, I stumble on a little piece, I forget the title – but it hooks me right away. A feminine voice, a ukulele – and that’s it.

A name like a gunshot: Barbara Browning.

I love it, so I “like” it, and I leave a little comment. Then I visit her page, with hundreds of covers, all in the same minimalist style. I always loved miniatures.

7 January, 2014 – I haven’t forgotten the date. What happens? I’m just about to catch the train to Paris when a strange fly bites me. I grab my guitar, three chords, a little reggae rhythm, and the words, like the music, come to me on their own.

The music is light, the words less so:

Cette fille est un killer

Et moi j’ignore encore

À quoi le destin me destine.

Mais si je meure avant l’heure,

La tête, le coeur, le corps,

Oh! Que ce soit d’un coup de Browning.

Barbara Browning.

Barbara Browning.

That girl’s a killer, and me, I still don’t know where destiny’s leading me. But if I die before my time, head, heart, body, let it be of a shot from a Browning… The title of the song? “Barbara Browning.” I just have enough time to record it and post it on SoundCloud before I catch my train.

Once I’m on board, I bite my fingers. Such a personal song, with the name of a stranger for a title, that’s a bit presumptuous, no? What if she sues me? Americans love to sue, and Barbara’s American. Getting off the train at Saint-Lazare, I just have one thing in mind, to plug my computer in and correct the error by taking down the song. But the dice are already cast: the first comments and “like”s have already appeared, so I content myself with rebaptising the tune, removing her first name. After all, a Browning is a fairly ordinary object. And then I forget about it.

Until the next day. Not only does it seem that Barbara Browning doesn’t intend to sue me, but she’s even sent a response, tit for tat, as it were, in the form of a cover of one of my songs: “Tu veux de l’or.” You want gold. Direct hit. A few private messages follow. Something’s taking shape. I take a closer look at her page. Identifying factors – a photo, the name of a city, and a short text. The photo: head cut off, and the sketch of a body in a knowing penumbra – it looks to me like a girl who could be one of my daughters. The city: New York. As for the text, it’s just a few lines followed by “see more…” – but I read the snippet quickly and don’t want to know more.

In one of her first messages, she throws me a question: “Who made you up?”

That strikes me. Me, I know the answer, but it can’t be explained in a short online message, and how can I plunge via email into a story that’s taken place across forty years? I leave it at this: “It would take a fireplace and a good bottle of Vouvray to tell you that…”

Meanwhile, I propose to Barbara that we record a long-distance duet, with a certain intuition that our voices would go nicely together. The assonance of “Browning / Lodbrog” encourages me. She says okay:

if you send me an mp3 and some words, i’ll sing wherever you tell me to, whatever you tell me to. then i’ll send you an mp3 of my naked voice, and you can mix it in however you like. if you insist, i’ll send my track “dry,” which in english means with no reverb whatsoever. that’s not particularly flattering. the gentlemanly thing to do is to allow a woman to send her voice at least a little wet. 🙂

That last bit sounds a little naughty, so, all right, I’ll be a gentleman. The theme of “Beauty and the Beast” occurs to me. Parodying the famous song from West Side Story, on the train from Paris to Evreux, I mentally birth a waltz in Franglais, “I Feel Ugly,” in which, in alternating phrases, one loses track of just who is ugly and who is pretty. I record it, and send it along with the lyrics typed in red for her, blue for me. A few days later, the song is posted on SoundCloud and is received as a frank success by our followers. That encourages me to dive into another duet: “Down and Up.” Then comes “Naked Lady with a Ukulele,” and some others… It’s February, and we practically have a repertoire already. One day she asks me to do a cover of Gainsbourg’s “Initials BB.” I whip it off right away, and from that moment on I take to calling her “Bébé”.

That’s when Bébé advances a pawn on our little chessboard. “I don’t suppose,” she asks in the negative interrogative, “that you could get to New York next month?” She could organize a concert for us on 15 March.

She doesn’t know about the joker up my sleeve. I tell her, “You suppose wrong.” My son Tom works for Air France. As his father, I have the right to five roundtrip tickets per year to any location they fly, for a nominal service fee. Bébé doesn’t seem displeased. She presses me to get my ticket: “vas-y, imre, buy your damn ticket, throw caution to the wind.” I love this phrase. I obey and reserve my place on a flight on the twelfth of March.

From that point on, the scales are tipping toward the improbable. I begin to think I’m dreaming, and to fear I might wake up, branded as I am by Calderón’s play, La vida es sueño, in which the hero is yanked from the damp straw of his dungeon only to find himself flung upon a throne – before being tossed once again back into his dungeon.

All that mixes in my head like a slightly troubling cocktail. A few signs of disorder appear. When it takes a while for Bébé to answer an email, my nervousness gets the best of me. That old feeling of being on a high wire. And what if all that were just a joke, a passing fancy of a few days, a flash in the pan? What can one know, in fact, about these millions of Internauts, in their exchanges where nothing actually connects to anything, since one’s knowledge of the other is 99% virtual? But the messages keep coming, and Bébé appears to be steadfast, gently setting my worries to rest. Then, just to feed my anxiety, I start to invent other possible problems: a surprise strike by the employees of Air France – or the outbreak of World War III (which doesn’t even need to break out; the world is already unraveling daily).

But finally, on 12 March 2014, I find myself nicely set up, ready for boarding at Roissy Airport. Tom’s arranged everything, alerting the crew to my presence on the flight. I’m led like a VIP to the upper deck of the A380, where I’m placed in a business class seat, the first glass of champagne in my hand. I lift it, in my mind, to Freddy. When the plane takes off, I’m already on my third glass, and I’m flying.

Where am I going? Toward what? New York! One of the great loves of my life. From my first visit there in the ‘70s to the last in ’98. Something of an obsession. I didn’t think I’d ever get back there.

And Barbara Browning? A few hours before meeting her, I go over what I know of her, which is the sum of what she wanted or judged necessary for me to know, since I’m an adamant anti-Googler. I know that she’s a musician, and a professor at NYU. I also know that she is a dancer, and that is no small part of what I know of her. I’ve always had a problem with dance. When it wants to make us forget the laws of gravity and our physical weight, it does nothing, to my eyes, other than to remind us of it. Attempts at flight which always evoke for me the “Albatross” of Baudelaire. But I adore Fred Astaire, Michael Jackson, Farid Chopel… And I love Barbara Browning.

She’d sent me the links to her YouTube dance videos. As with her covers, we were dealing with minimalist miniatures. The first of these videos was called “Celebrate the Body Electric.” Over a soundtrack of piercing electric guitar, a young man with a naked torso enters the frame and begins to flail. He’s soon joined by a girl, and the two go wild, reaching a state of trance, the girl flipping her hair around like a madwoman. The girl? Bébé. The young man? Her son. They could’ve been a young couple on Ecstasy; it was completely uplifting. In another clip, to one of Satie’s Gnossiennes, it’s a ballerina who uses her body like a marionette, articulating and disarticulating her moves at the ends of invisible strings with a Chaplinesque air. And last, my favorite, her “iPod Samba.” Just a woman dancing in her room with her headphones on, in jeans and sneakers… And smiling as she does.

Finally, I know she is a novelist.

I’ve always found that the books that one loves can be the best way of presenting oneself. I was still under the shock of L’Homme qui rit, which I’d discovered late. I’d recommended Hugo’s novel to her, which she devoured in a few days. In exchange, she had mailed me her first novel, The Correspondence Artist, into which I’d plunged, imagining it to be a work of pure fiction. I was immediately hooked by the liveliness of her voice, her finesse, the mix of humor and emotion – but I was also intrigued and a bit disconcerted by its form. Written in the first person, it seemed to have the scent of an autobiographical account, fed from life with a sense of detail that, as we say, doesn’t fool anybody.

Suddenly, it seems like I’m entering the intimate universe of a stranger, one that I’m only beginning to know, and in spite of the pleasurable reading, that’s disconcerting. The book exhibited, unvarnished, sexual relations of all kinds, ranging from a young male lover to an older mistress, from Israel to New York passing through Mali in an expanse of raw details, making of the reader an eyewitness – even an involuntary voyeur. I had some difficulty untangling the skein. Fiction, or an intimate journal? I know Bamako well. In the middle of a chapter in which the author finds herself there, I rediscover not only the perfumes and colors but also the precise topography of the place. And I asked myself who could be this “Djeli,” the famous musician that she went to meet there, and who had an aversion to oral sex… All of it read like irrefutable lived experience.

But actually, I’d penetrated a literary genre previously unknown to me. Neither real nor fictional, half-real, half-fiction: fictionalization of the real. And Bamako? Bébé had never set foot there! As for her amorous confessions, I’d soon learn that that apparent multiplicity of liaisons could be reduced to a single one, and a bit in the style of Chateaubriand’s Sylphide, she had fabricated a sort of collage of fictional personae as the portrait of one person, entirely real. Each time I dived into this tissue of confidences, especially on the sexual level, and in spite of my delectation in the text, I quickly ended up asking myself: Do I really want to know all this right now? Wouldn’t I rather hold on to that smoky halo through which the image of the Other would reveal itself in its own time, if at all?

I was hoping to tell my backstory in little bits, over time, on long walks through the streets of New York… Or maybe not telling it at all. In short, mystery seemed to me the more appealing option, and I’m ashamed to say that I left my reading in mid-course. Not without promising myself that I’d take it up again one day.

I should mention her inscription: “To Imre, who could have been a character in this book, and surely will be in one to come…”

And one other detail, because she’d said it more than once: Bébé was a feminist. Why had she insisted on this point?

So, there I am, on the upper deck of that Airbus A380, seat number 72 (the year of my first visit to New York), and that’s more or less what I know of Barbara Browning. A few hours later, after I’ve downed a few drinks and watched, yet again, with great pleasure, Godard’s Breathless, the voice of the flight attendant announces: “We’re beginning our descent to John F. Kennedy Airport. Please fasten your seat belts. The ground temperature is…”

I pinch myself. It hurts. That’s a good sign.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.