The Governesses by Anne Serre teases its readers with elements of allegory and fairy story. Three young women stroll through the gates of an enormous manor house which is the kingdom of Monsieur and Madame Austier, and home to a cluster of little maids and boys. Eléonore, Laura and Inès are the titular governesses and extraordinarily lacking in those roles. It is immediately clear to even the densest of readers that no one would hire this trio to watch over guinea pigs, let alone children. As the narrator tells us – “You would even wager there was something fishy going on.”

Fishy, indeed. This “scatterbrained band of young women” seldom do the work for which they are employed: i.e. – educating the little boys in their identical sailor suits, who are forever rolling hoops up and down the stairs and looking for all the world like the faceless figures in an M.C. Escher drawing. Instead, the governesses prefer to spend their time lolling around naked in fields, performing lewd pantomimes for the elderly gentleman who spies on them from across the way, and ravishing the strange and anonymous men who innocently “stray into the garden”. They behave, and are treated, more like pampered princesses than employees. Shallow and vain, if cell phones existed in their sheltered little world (and there is no indication that they do) Eléonore, Laura and Inès would be posting an endless stream of selfies to Instagram. #BlessedLife.

All through the house, on the stairs and landings, little boys march up and down, passing each other in silence. Sometimes a hoop trundles down the stairs and bounces across the wide hall. Only once does it go all the way through the wall without stopping and on into the salon, catching on a vase on one of the side-tables. Whereupon children arrive half a dozen together to pick up the pieces.

But there is no technology, and the young women live an analog existence confined within the gold tipped iron fence. It is unclear whether Eléonore or Laura ever travel beyond that fence and into the outside world, though we are told they had lives before joining the Austier household and their strange entrance/first sighting is described to us by the chatty narrator who appears to be Serre, herself.

The day the governesses walked into the garden, Monsieur Austeur was standing behind net curtains in the salon, keeping an eye out for their arrival. They advanced single file: first Inès in a read dress, weighed down with hat-boxes and bags, then Laura in a blue skirt, and, bringing up the rear, Eléonore, who was waving a long riding-crop over the heads of a gaggle of little boys. He was amazed. It was life itself advancing. He rubbed his hands and began jumping up and down in the salon.

Inès is the only one we can say with complete confidence ever leaves the grounds. She is, on occasion, sent to care for the elderly gentlemen across the way. As for Monsieur and Madame Austier, they and the little maids are away at the seaside when the story begins.

Regardless of who comes and who goes, all the action takes place within the geographical borders of the property. Even when the young ladies attend an engagement party there is “no need to leave the premises to reach the neighbors’ house. There’s an opening in the woods that leads straight into their garden, where four red and white striped tents have been installed, with little streamers fluttering in the wind.”

Anne Serre has written a self-contained novella in which she plays a delightful docente – a friendly narrator pointing out small treasures for us to marvel at. Her voice is playful, gossipy, and indulgent. She is both charming and charmed. But her story lacks a traditional structure which, predictably, hurts the overall pacing of the story. This is a very short book with very little plot. So voice, and every word choice which contributes to it, matters. Fortunately, Mark Hutchinson seems to have chosen all the right words.

The engagement party is one of a series of carefully composed set pieces out of which The Governesses is fashioned. Outside of their gilded cage something strange happens. Eléonore, Laura and Inès lose their luster and become three young women with nothing particular to recommend them. Clinging to the edges of the gathering, unable to make conversation with the other guests, nursing glasses of punch and desperately wanting to leave – in this setting, away from their employers and the eyes of the elderly gentleman, they do not “shine”.

They’re no longer young swallows returning home but poor, crestfallen young women who don’t dare look each other in the eye. They go up to their rooms in silence. And who, I ask you, on such an evening, would be so heartless as to follow them?

The elderly gentleman, as he is always called, observes the world of the governesses through a telescope and is essential to their continued existence. (If a governess falls in the garden and no one is there to witness, does she make a sound?) We, the readers, are provided with an even wider lens, one wide enough to contain even the gentleman within its field of vision. The house and garden is a terrarium into which we peer like Victorian naturalists. The inhabitants are exotic insects or small, wild animals whose life cycles we gather empirical data on. Their animalian nature is exaggerated. We watch, riveted, as the three young women go into estrus and lure a potential mate for the purpose of their own sexual gratification and, possibly, the breeding of new little boys. Then, goal achieved, they cut the poor man loose to stumble, dazed and drained, back through the gate and into the wide world. Comparisons to the praying mantis lead us to believe that he is lucky to survive the encounter.

There is something inhuman about all the characters, not just the governesses. The little boys exists in schools like fish, with one boy or the other only occasionally and tentatively breaking rank to assert his autonomy before being happily reabsorbed into the collective. The little maids, who may be the boys’ sisters or household servants, are always together. The two groups seldom intermingle on the page.

Scale does not exist in the terrarium – the young women grow to gigantic proportions, becoming naked giantesses with rude and saucy dispositions…. only to shrink down again a few paragraphs later, their dresses puddled around them. All without the aid of bottles and cakes.

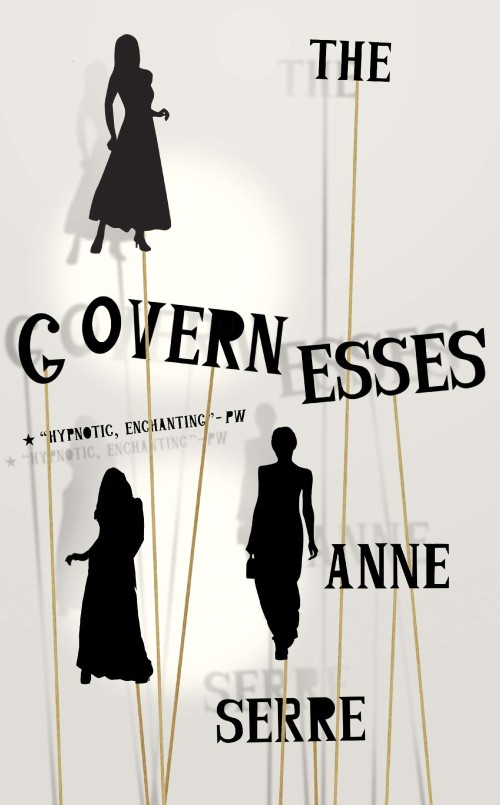

The Governesses seems to invite all the obvious – too obvious – comparisons to The Virgin Suicides, The Beguiled and Picnic At Hanging Rock. Those late 20th century abnormal psych experiments masquerading as novels and, eventually, films. With their plots centered on small groups of sexually charged females living in semi-isolation, the shortage or complete absence of men making them slaves to their latent sexual desires. But, in truth, there is no similarity. Instead, Serre’s tale has more in common with Vanity Fair, the once popular novel by William Makepeace Thackeray which has suffered through its own endless movie adaptations. Both writers treat their characters as toys – dollies and puppets brought out of their boxes entirely for our amusement. We are invited to play along, enjoy their antics and, when their time is up, watch as their creators neatly (and with very little fanfare) pack them away.

The problem with allegory is that it is malleable – representing one thing to the reader, while the writer can claim that he or she intended something else entirely. It’s designed to frustrate and bedevil. Every noun takes on symbolic significance. Every sentence seems to be an allusion to some other work. So, whether there’s a method or a moral to Anne Serre’s tale, who can say? The allegorical fable by its nature lends itself to visually striking imagery like no other literary form. This is exactly what Serre places before her readers – a visual feast, a cabinet of curiosities, a long gallery filled with self-contained dioramas for us to stroll past and admire. Serre tells a tale meant to bewitch and delight her audience for a finite duration… presenting us with the perfect diversion. She succeeds brilliantly on every count, demonstrating both exceptional clarity of tone and agility of invention. Fourteen of her novels have been published in France, the first in 1992, along with an enticing abundance of essays and novellas of which The Governesses is the first to be translated into English. We can only hope more will follow.

***

The Governesses

by Anne Serre; translated by Mark Hutchinson

New Directions; 112 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.