The Trash Man’s Daughter

by Vic Sizemore

She was one grade above Malachi, but two years older. Her name was Lydia Cumba, and in Malachi’s fifth year, she showed him that life was more than toy cars, bicycles, and baseball. Lydia was seven and Malachi five when she tried to teach him about sex. To Malachi, sex was still a strange and forbidden world: his dad was a Fundamentalist Baptist preacher. Malachi heard an older boy at church call another boy a cunt, and carried the word home to use on Matthew—his mom rubbed Ivory soap on his tongue, made him rinse and spit, then did it to him again. His dad would not even use words like panties and boobs unless he was quoting an unsaved person.

Malachi was playing at Lydia’s house while their moms were inside using mom’s new juicer on carrots—his mom’s excuse to leave a bunch of vegetables at their house. They were poor. Malachi’s older brother Matthew and sister Martha had set out to hike through the woods to the beer bottle tree which was down by the banks of the mud-brown river—a spanking for sure if they got caught. Lydia, her sister Deborah, and Malachi stayed behind.

With the older kids gone, they set out on an adventure of their own. Lydia and Malachi pretended to get married. Deborah, who was also five, was the preacher, and she pulled her chin in and spoke with her impression of preacherly gravitas in the pulpit.

When Deborah said, “You may kiss the bride,” Lydia leaned out and kissed him on the mouth. Her breath smelled like oranges.

Deborah hooted and laughed, and said, “I’m telling.”

“If you do,” Lydia warned her, “you’re dead meat.” Then she said to Malachi, “We need to kiss again. That’s what husband and wife do.”

They did, and he felt inside like he was flying down Shafer Hill on his bike, pedals spinning so fast he couldn’t get his feet back on to hit the brakes.

“There’s something else husband and wife do,” Lydia whispered, her orangey hot breath on his ear. “We have to lose Deborah.”

He scrunched his eyes at her.

“You’ll see.”

They ran around the house and the trailer, Deborah running behind calling, “Wait up.” Their dad framed up a house beside their trailer but then had apparently given up, or run out of money. Malachi’s dad said it was proof that Lydia’s dad was unwise. “Which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first, and counteth the cost?” his dad quoted Jesus. Lydia’s dad was a trash man during the day and cleaned the grade school at night.

Once over dinner Malachi’s mom had said, “I feel so sorry for the poor man. He tries so hard.”

“Nothing’s going to work out for him,” Malachi’s dad had told her, “until he turns his life over to the Lord.”

His mom had sighed and got up to scoop more mashed potatoes from the pot to the big bowl.

Lydia’s mom worked too, made ice cream cones at the Tastee Freez. Lydia and Deborah stayed with her aunt Betty and Uncle Jim a lot when her mom and dad were both working.

A grassy alleyway ran between the unfinished house and the trailer. Lydia and Malachi ducked into it and Lydia dragged and propped a piece of plywood across the entryway. Lydia’s dad had black fifty-gallon drums in there that he’d welded together for a homemade pontoon boat. The pontoons lay side by side like two massive Tootsie Rolls with red-orange rust on them, and weld rings like lumpy scars on skin. Her dad had abandoned the boat project and the barrels were slowly settling into the earth and weeds. They had about ten feet from barrels to board.

“I’m telling,” Deborah called out as she walked by and they held in their laughter.

Hidden in that dank, weedy space, Lydia got Malachi to agree on pulling down their pants at the same time. They stood looking into one another’s eyes.

“Look,” she said. She pulled up her shirt and showed him her chest. It was a flat chest, not any different from his, except she had a scar that looped around her left nipple and curved under her arm. “I had a hole in my heart when I was a baby,” she said.

He stared at the scar. It was red and tender looking. “Does it still hurt?”

“It itches,” she said. “Now pants and underpants.” She unsnapped her cutoff shorts and pulled down the zipper.

Malachi unsnapped his and unzipped them. His hands shook.

Lydia had on white panties with little pink animals all over them. Dogs. Pink dog shapes.

“All the way down,” she said. “Don’t chicken out.”

He assured her he would not.

“One, two…” and as she said, “three,” she bent over and pulled down her shorts and panties as if she were sitting on a toilet. He did the same.

Malachi stared at the rounded slit between her skinny legs. Where he had a peebird she had what his mom called her girl parts, he knew that much. It was nothing but a mound of smooth skin. Why did it have some kind of secret power over him? His peebird was hard and his legs weakening. He thought he might fall down they were so shaky.

“Your dick’s all hard,” Lydia said. “That means you love me.”

He knew she was right: this was love. He was in a strange dream, hovered two inches above himself and stared down at the scene, watched in joy and wonder.

At that moment, four angry knocks rattled the trailer’s kitchen window just above them.

Lydia knew exactly what was going on. She bent over and squirmed back into her panties and shorts, and was fumbling with the plywood before Malachi had even gotten my shorts up.

Four more hard knocks.

Her mom’s angry face grew large as it neared the window. She pointed her finger at Lydia and said something. Her mouth made a square shape then closed tight. Her hand was close to the window, ready to knock again. The other was up beside her ear in a yellow rubber dish glove.

By the time Malachi got around to the front of the trailer, Lydia was crying as her mom arm-yanked her up the cinderblock steps and into the trailer. His mom stepped carefully down the cinderblocks, her mouth her lips puckered as if to kiss.

“March it home, young man,” she said to him and she pointed down their rocky dirt driveway.

He walked in front of her up the street, walked behind the church, where his dad was inside recording the week’s sermon for the Sunday radio broadcast, walked up the concrete steps, through the back door, and into the kitchen of the parsonage. He turned around and stared at the brown and gold squares and diamonds on the linoleum floor. A gouged-out triangle near the table leg was black with grime.

“I’m going to tan your hide,” his mom said. She shouted and raged, and told him that he must go out and find her a switch.

He tried to get a small one, but the small ones stung too. She switched him with all the fury of her embarrassment that day. She lit his legs up with what felt like a swarm of bee stings, and he cried until he gulped down air. She sat him on his bed, kneeled in front of him and locked eyes. Her breath smelled of coffee. Malachi noticed for the first time her eyes had changed. They had turned yellow. She lectured him about girls’ bodies and boys’ bodies and something she called “sexual purity,” which he did not understand.

“Why are your eyes yellow?” he asked.

“Don’t change the subject,” she said.

“But why are they yellow?”

“What in heaven’s name possessed the two of you to do this?” she asked.

Malachi recounted everything they had said and done. She sat on the bed beside him for a long time, and then said, more to herself than to him, “A girl her age shouldn’t know the things she knows. Something’s not right over there.” She stood, and as she left she said, “You are grounded to your room for one hour.”

Malachi sat scratching the itchy welts she’d left on his legs. The excitement of having glimpsed Lydia’s girl parts had mysteriously brought his young body to life, and only later blended with the shame of having sinned. He was also puzzled about what was turning his mom’s eyes yellow—he knew from her expression when he asked it was something bad. All the mixed emotions swelled until he could not take it; he stared out the window and cried aloud until the weeping took on rhythm and sounded like a chant, and he came to himself with the realization that he was not crying anymore, but entertaining himself with rhythmic moaning. He fell silent and wiped his nose on his top sheet.

His mom popped her head in and said, “Where are your brother and sister?” He lied with a silent shrug of his shoulders.

Malachi was no longer allowed to play with Lydia, and his mom’s enthusiasm for friendship evangelism with her mom withered and collapsed. His mom got sicker. The yellow in her eyes grew dark and shiny, and her skin turned course and brown. He saw Lydia every now and then, but she was older, and in public school, while he attended Meadow Green Christian School because of the public school textbooks that taught modernism, secularism, and situational ethics.

Seven years went by in which Malachi and Lydia did not speak to one another. Her dad moved from driving a trash truck to fixing them in the trash-truck garage across the road from Malachi’s house. When Malachi stepped out the front door of the parsonage, his bike always lay in the grass beside the driveway, summer or winter. The reek of trash from across the road. Two garage doors staring like pit bull eyes. His dad’s church to his left, around fifty steps across a parking lot to the glass double doors. Along the side of the church building at ground level was a row of dark sliding windows. If you were down in one of the basement classrooms, these windows were up by the ceiling.

One Sunday after church, Malachi stood on a table and unlocked the window in the Awana Sparks classroom. When bored during the week, he slid open the window and dropped to the floor in the dark classroom. He snacked on candy the teachers kept as treats, and even sometimes took the quarters out of the plastic white church banks. He wandered the dark church, eventually made his way upstairs and ran across the backs of the pews because no one was there to stop him.

Malachi was in seventh grade, his sister Martha was in tenth, and Matthew was in his first year studying youth pastoral at Pinewood University. Their mother had just lost her battle with chronic hepatitis and gone to be with the Lord and single, eligible women were hovering around their house now, bringing food, fawning over Malachi with their awkward attention. Joyce Ramsey told him his mom had contracted the disease from a blood transfusion after giving birth to him. He did not blame himself, and no one else seemed to blame him either, but why did that woman feel the need to tell him? It was a strange and uncomfortable knowledge, and now it would be forever the first scene in Malachi’s life story.

One day, when he and his sister got on the ERCS school bus, Lydia was over at the trash truck garage with her sister Deborah. Malachi’s own sister Martha sat down beside Timmy Wells, their school’s star all-around athlete—he was good enough to be a star at their Christian school, but not good enough for public school—and Malachi sat in the seat behind them with a third grade girl in a bright blue dress with fat white buttons down the front. She had a Wonder Woman lunch box on her lap and she smiled wide at Malachi so he said hello.

“Who is that?” Timmy said.

“That’s Lydia,” Martha told him. “She’s a total sleaze.”

“She’s hot.”

“If you’re into sluts,” she said.

“What’s not to be into?” Timmy laughed. “Oh man, I have to meet her.”

“You’re incorrigible,” she said.

Timmy teased Martha for using the word incorrigible—he pocketed the word and, apparently, without ever bothering to find out its meaning, he and his friends pulled it out to tease her for the rest of the school year.

On many days, after school Malachi would peek out his bedroom window at Lydia over there at the garage. Days when she had volleyball and didn’t ride the bus home, she walked down from the Super Value and rode home with her dad when he got off work. Malachi watched her from behind his curtains as she leaned her weight from leg to leg and her butt cheeks shifted inside her jeans. All her jeans were too tight—one pair worn so thin and almost white that her panty lines were as clear as if she were naked. He stood at the window in his dark bedroom wracked with guilt and despair and masturbated.

Looking out of the school bus at Lydia, Martha said, “Screw her if you want to. Everybody else does.” She said, “I’m just saying you’d better have some penicillin handy.”

It was cold outside. Lydia bounced lightly on her toes and hugged herself. Her white ski jacket was old and the sleeves were filthy along the forearms. Her sister Deborah looked like a boy—cut her hair, dressed, and walked like a boy. The bus jerked twice and started to move. The little girl beside Malachi held up her lunch box in front of him. “Wonder Woman,” she said.

Some days, the trash trucks wafted the sour stink of house trash; other days it smelled of rancid meat, of rotting flesh, of death. Most of the time it radiated a low-intensity odor of oil, diesel fuel, and bearing grease. The parking lot had gone bald of gravel in places that were slick black with oil and grime. When it rained all fall, water slid across them in rainbow beads. As winter came, the mornings he left for school, frozen puddles were swirls of air bubbles and fractal patterns. The puddles reflected the sky, and Malachi stared down into them as if at his own anti-self in a parallel dimension.

Since his dad was the kind of preacher who was always witnessing, always handing out gospel tracts, the trash men and mechanics steered clear. The men over there were laboring beasts in green and tan coveralls and jackets with grease-blackened elbows. They were only half a football field away, but so removed from Malachi’s world that they might as well have been shifting images on a TV screen. Malachi and his brother were like puppies first opening their eyes to the world back then, and their awareness seldom spread more than a few feet from their bodies.

The day Malachi stole the tobacco, it did not occur to him that there were windows in the bay doors, and windows along the upstairs floor—dark spaces surrounding him that could have all been full of silent watchers. He did not consider this until later, after Lydia’s dad chased him down. He was not much taller than Malachi, in saggy jeans and a dirty short-sleeved shirt with a stretched breast pocket.

“You’re a dirty fucking thief, boy,” he said.

“Am not.”

“I watched you with my own god-damn eyes.”

Malachi stared ahead in silence.

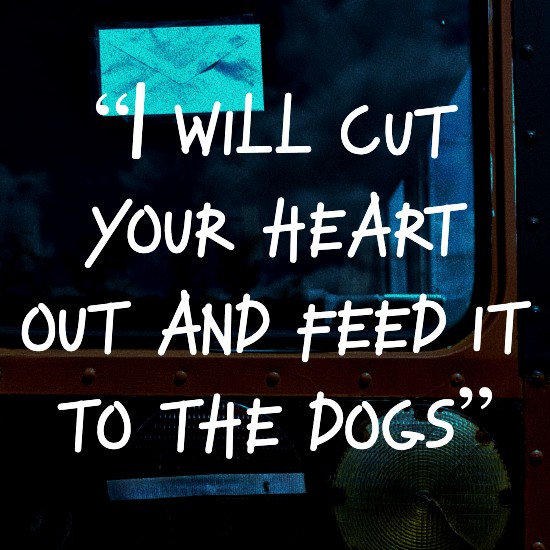

The man lifted a pocketknife and held the blade in front of Malachi’s face. The scrape marks were of a knife sharpened often—he was probably a man who shaved off bits of arm hair to test its edge.

“I will cut your heart out and feed it to the dogs,” he said.

Summer came. One day after school, as Malachi was on his knee sliding open the church’s basement window, he noticed that Lydia was over at the garage in tight cutoff blue jean shorts watching him. He stood up and waited for an awkward thirty seconds as she walked toward him, swaying her hips and grinning.

“You breaking into a church?” she asked. She had on dark blue eyeshadow and heavy eyeliner. She smelled of cigarettes. “Won’t you go to hell for that?”

“Just messing around,” he said.

“Can I come?” she asked.

“Sure,” he said, stammering, “yeah.” He said, “It’s a drop to the floor.”

“Don’t you worry about me.”

He dropped inside, and watched as she lowered herself in. The backs of her legs had striated, dimply dents. Her shirt caught on the windowsill and exposed the bare white skin of her back. He cupped his hands into a stirrup and put them under her foot. Her butt was only inches from his face.

“Get back,” she said, kicking at him with her sneaker, her arms and head still outside. “I can do it.”

He backed away.

The basement hallway smelled of mildew. He led her to the steps, and they went up to the sanctuary. While the back wall was made of windows showing the world outside, the road, the neighbor’s house, the trash truck garage, inside the sanctuary was dark as a crypt.

Malachi stood at the back of the middle aisle and faced the bright wall of windows.

“Get down,” Lydia whispered hard from the steps.

“It’s dark in here and light out there,” he said in his regular speaking voice, which sounded loud and booming in the cavernous sanctuary. “You have to put your face up against the glass and cup your hands around your eyes to see in. Even then, you can’t see much.”

“What is that light?” Lydia asked.

Malachi turned to see that the radio room light was indeed on.

“My dad’s in there,” he said. “Taping a sermon for his radio show.”

“Your dad’s on the radio?” She sounded impressed.

Malachi balanced on the back edge of the last pew, stepped forward onto the next, and the next, and the next, until he was at the front of the sanctuary. He turned around and returned to the back of the church, quickening his stride.

“You are so going to go to hell,” Lydia said.

“Come on.” He quickened his steps until he was virtually running across the backs of the pews.

On another trip from front to back, Malachi glanced up at the back wall of windows. The bright sunlight outside blackened the sanctuary around him, and Lydia’s silhouette was climbing onto the back of two pews. It threw his rhythm off and he missed a pew. He threw out his hand to catch himself, but the pews were still dark to his sight. He landed across a pew back on his rib cage and yelped out in pain as he rolled into the pew.

He could not breathe in enough air to cry.

“Oh my god,” Lydia whispered. Her face hovered above him. “You okay?”

He lay in the pew, held his ribs and caught his breath.

“Is anything broken?” She hunkered on the pew beside him and her face was low, close to his. Her breath was warm and had the low-intensity stink of saliva. A roll of flesh bulged between her jeans and her shirt, creased at her belly button into a wide Joker smile. The side of her leg was dimpled like the back. Without thinking, Malachi reached out and put his hand on her tummy.

“I guess that means you’re okay,” she said. “You little pervert.” She did not remove his hand.

The radio room door handle clicked.

Lydia jumped to her feet and Malachi sprang up and held his ribs.

“Go,” he said, and pointed at the stairs.

“Hello?” his dad’s voice called out as they descended the steps. “Who’s in here?” Moving toward the steps, his dad’s voice yelled, “Hello?”

They sprinted down the dark basement hallway, their laughter echoing around them. The back door had a small square window with chicken wire in the glass, and it glowed with the bright outside day.

“Malachi,” his dad yelled from the other side of the hallway as they reached the door. As Malachi opened the door, she said, “Go,” and pushed him from behind. They sprinted to get around behind the church gym.

“Son,” his dad yelled behind him. “You come back here this minute.”

They ran behind the gym and down the hillside toward the clearing. They ran alongside the softball backstop and the picnic shelter. Malachi turned around to see if his dad was chasing. He was not. He had not even come around the gym. They started walking and catching their breath. They walked the narrow path in the weeds down the riverbank to the sand bar.

They stood together looking at the river. It had not rained for over a week, and the normally muddy river was clear and green.

They stood holding hands and watched the river’s endless flow.

“You in trouble?” she asked.

“Probably,” he said.

The lecture Malachi’s dad delivered later that evening was not about disobedience or disrespect to the house of the Lord as he’d expected, but about the danger a loose girl was to his soul. His dad quoted Proverbs 5, how “the lips of an immoral woman drip honey… but in the end she is bitter.”

Lydia was in ninth grade. Fifteen years old. Malachi suppressed a grin.

“This is no joke, son,” his dad said in his deep, preacher voice. “One day you will meet the right girl,” his dad told him. “A girl who has kept herself pure.”

Martha came into the house with her boyfriend as the lecture wound down, and heard Lydia’s name. “What are you doing hanging out with her?” she said to Malachi. “She’s a skank.”

In September of Malachi’s sophomore year at Woodrow Wilson when Lydia’s dad shot and killed her mom’s brother, her uncle Jim. The following Sunday, Malachi’s dad used the event as the introduction to his sermon. He said the sins of the flesh—including the violence that plagues the human race—are jagged rocks at the bottom of a riverbed. They are always down there, but the Holy Spirit is the water. The fuller you are with God’s spirit, he said, the less those jagged rocks down there can harm you or anyone else. “It’s when the water of the Spirit dries up,” he preached, “that people crash their boats on those stones of violence and sin.”

Lydia’s dad went to prison. Lydia and her mom disappeared from the neighborhood.

When Malachi was a senior at Pinewood University, double majoring in religious studies and English literature, Lydia turned up at his dad’s front door. Although Pinewood was less than twenty miles from his house, Malachi lived on campus, to get the full college experience and to get away from his dad’s new wife, Patty Blevins. His dad had courted and married her Malachi’s first year at PU, the year after her husband, a longtime deacon in their church, had died of a heart attack. She’d moved in with a fastidious possessiveness that somehow transformed Malachi into an uncomfortable guest in his own house. He didn’t resent her for it. He was on his way out and it was her new home. Still, he didn’t want to live there anymore.

He was back in the old house over Christmas break. Matthew was there with his wife and their three kids, and Martha was there with her husband and two boys, only thirteen months apart, both still in diapers. Malachi’s girlfriend had gone back home to Pennsylvania for the break—they were sleeping together, but hadn’t progressed quite to sharing holidays or saying I love you, though he did love her. The festive Christmas lights Patty had strung on the tree blinked and the house was hot with the smell of clove and cinnamon wassail. Malachi imagined the walls bowing outward, the house was so full of bodies, noise, and clutter.

He was in his dad’s easy chair half-asleep, half watching the older kids play Mario Kart. Patty was playing with the little ones while Martha took a nap in back. The doorbell rang, and Malachi’s dad answered it. Malachi could hear his dad’s side of the conversation, could tell someone was asking for money. A female voice. Curious, he closed the footrest on his dad’s chair, stepped into the foyer, and looked over his dad’s shoulder at Lydia.

It took him a few long seconds to place her—she had gained significant weight and her face was weathered as an old ball glove, framed by the frizzy curtains of her winter-dry brown hair, already streaked through with gray.

“You come back with a letter from the Salvation Army attesting to the need,” his dad was telling her, “and I’ll be happy to walk over to the food pantry with you and get your kids some food.”

“The Salvation Army’s all the way downtown,” she said. “And they’re offices don’t open again until tomorrow morning.”

“They’re open twenty-four, seven,” his dad said.

“Not the goddamn—” She took a deep, shaky breath. “I really appreciate it,” she said, “but I need money. My heat’s cut off. I have two kids.”

It was in the low forties, raining a little, not cold for Christmas in Meadow Green, but not balmy if you didn’t have heat.

“Where are they right now?” his dad said.

A strange grimace that could have been pain or panic moved across her face, but she regained her composure fast. That’s when she glanced over Malachi’s dad’s shoulder and they made eye contact. She stared blankly at him for a moment. “Thanks anyway.” She turned to leave.

Malachi pushed past his dad and called out, “Lydia.”

She stopped and turned around.

He ran out to her in the driveway. It was drizzly and cold. Their breath seeped out in white puffs like the spirit leaving a dying body in a horror movie. The trash truck garage was out by the interstate now, and the building across the street razed and paved over for more church parking.

“It’s Malachi,” he said.

“I know who you are.”

He dug in his pocket as he approached her. All he had was a twenty. “Here,” he reached it toward her.

She took it. Her thumbnail was purple, like a car door had closed on it.

“If you want, we can jump in my car and I’ll go to the ATM and get you some more.”

“In your car.”

“How much will it take to get your heat turned back on?”

She stared right at him. “No thanks,” she said.

“It’ll only take a few minutes,” he said. “I totally don’t mind.”

“I’m not giving you a blowjob,” she said. She stared with what he thought might be hate right into his eyes.

“Oh, no,” he said, holding up his hands. “That’s not what I meant.”

“Uh huh,” she said, turning from him. “Right.” She walked out the driveway, turned toward downtown, and kept walking.

Malachi stepped back inside the warm house. His dad closed the door, shook his head and said, “Sad. The ravages of sin.”

“Who was that?” Martha was up, back in the kitchen holding a mug under her chin with both hands, her elbows tucked in.

“You remember Lydia Cumba?” Malachi said.

“That was Lydia Cumba?” she said. “Wow.”

“Sin is a hard mistress,” his dad said.

“Not surprised,” Martha said. “She was a slut from day one.” Her youngest toddled up and held his arms up to her. She set her cup on the counter and bent over, groaning as she lifted him.

The happy beeps, boings, and whistles of Mario Kart rang out in the living room. The shifting game-screen lights mixed with the bright Christmas tree, flickered and flashed in there.

Malachi squinted at her. “If you had her life, you’d be dead.”

“Goodness, Malachi,” she said, “what crawled up your butt?”

This made both the child in her arms and the one out of sight in the kitchen burst into hysterical laughter. Martha smirked. The child in the kitchen repeated, “What crawled up your butt,” and the two kids laughed until they both had the hiccups.

Vic Sizemore is the author of the short story collection I Love You I’m Leaving, published by Big Table Publishing, and the essay collection Goodbye My Tribe, forthcoming from The University of Alabama Press. His fiction and nonfiction appear in Story Quarterly, North American Review, Southern Humanities Review, storySouth and many other literary journals. His fiction has won the New Millennium Writings Award and has been nominated for Best American Nonrequired Reading, Best of the Net, and several Pushcart Prizes.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.