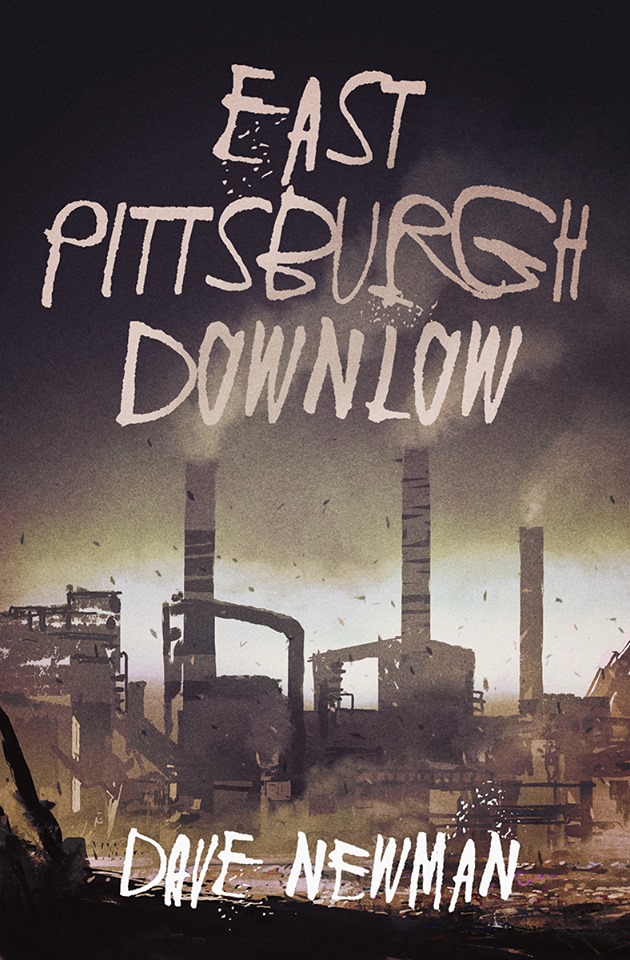

We’re very happy to be publishing an excerpt from Dave Newman’s new book East Pittsburgh Downlow, out now on J.New Books. As its publisher says, “Pittsburgh’s most famous citizen, Mr. Rogers, said ‘In times of crisis, look for the helpers. East Pittsburgh Downlow is the story of the helpers. It’s the story of the helpless and people desperately trying to help themselves. In more than 600 pages, lives will change and end and people will be re-born. Families will be saved. Love will find love because that’s what love sometimes does.”

***

Backwards Motorcycle

This is a truth.

I heard it from the gossip-and-concern gang then I heard it from Rig.

During one stint in rehab Rig became frustrated or bored or the desire to drink overrode the desire not to drink so he walked out again and got on his motorcycle and drove to a bar and ordered a beer and a whiskey. He did that all night, same order, beer and whiskey. He drank until he couldn’t drink anymore then he did some blow with a stranger who recognized Rig as a Steeler and wanted to be his friend, the friend of a professional athlete, the most famous friend you can have in a city that is not New York or Hollywood, so the new friend kept offering blow and Rig kept doing blow so he could drink more because it was always about drinking, even success as an athlete was about drinking, about earning a drink, about winning championships and making money so you could justify waking up one morning and taking a break from all that greatness to get smashed. Rig drank until the bar closed, thanked his new drug buddy for the coke, then hopped on his motorcycle with intent to check himself back into rehab, mistake made, thirst quenched, start again, renew, get the greatness back.

But the motorcycle almost drove itself as he moved through the streets of Pittsburgh and he’d never really ridden around the city, not this late at night, not with so little traffic, not with so many green lights, not with the bike steering the man and so effortlessly.

Rehab could wait.

It was one of life’s constants: the sun, the moon, a counselor telling you not to drink. Rig kept great health insurance and rehab loved health insurance, and what was an hour with the moon out and the engine set to roar.

He drove downtown and crossed over one bridge to the North Shore and took another bridge back to downtown, yellow metal to yellow metal, and took another bridge, more yellow metal, over the same river, the Allegheny, and ended up in Millville, which was a couple main streets, one coming and one going.

He knew Millvale.

He ate at Pamela’s Diner sometimes when he wanted to be alone. He’d go late in the morning and order an omelet and the pancakes. The pancakes were not fluffy like the pancakes his dad made when Rig was growing up but more like crepes, only not that skinny, just huge circles, crispy around the edges, yellow hill of butter melting in the middle of the top cake. He’d douse them in maple syrup and pour syrup over his sausage too.

Now he turned around and headed to Troy Hill which is where rich women lived, he thought, he couldn’t remember, maybe he’d heard that on the news, maybe it was rich families, so he passed through then circled back and grabbed the 31st Street Bridge and ended up in the Strip, which made Rig hungry. Rig was always hungry. Beer made Rig hungry. Being sober made Rig hungry. Blowing through a street lined up to sell food made Rig starved. He could feel the food behind the glass and wooden storefronts, Peppi’s with their steak sandwiches on the cloud buns, the shitty pizza place that was really pretty decent after a couple beers, all those Italian stores with their buckets of parmesan cheese and little stands selling meatball sandwiches and hot sausage sandwiches. Other stands, away from the Italian stores, sold street Chinese food. He passed the little taco place, an empty metal cart at this hour, and the other Chinese place with the better eggrolls, and he remembered how the Chinese woman running the stand kept them hot on a grill but not burned. Rig realized he was driving the wrong way on a one-way street, but so what, and how late, and he kept on. He passed a butcher shop, sticks of meat hanging on ropes in the window. Could you sell meat like that, meat not in a refrigerator? He guessed you could. He guessed he’d bought some during one of his benders. He finally swerved onto a side street by Klavon’s Ice Cream where he once ate three Mallow Cup sundaes with the same spoon and wanted to order a fourth but it was becoming an attraction, big man on a little stool.

He downshifted to third then up to fifth gear and revved the throttle until he made Bloomfield, an old neighborhood where the Italians and the Poles still lived, all aging now, all fat and getting toothless, but very few black folk, not that it mattered, he was Rig, pro athlete. People only worried about black people when they were poor and by worried Rig meant terrorized. Fucking white people. He hated them but they were okay. Fine. Even sweet. Lots of good ones. Always sold the best drugs. Helpful as hell. But scared. Always scared. Middle class—he hoped to never end up there. Down or up. Preferably up. Way up. That’s why he liked money: no one fucked with you.

He cruised through Shadyside.

Shadyside was a shitshow of purse shops and fancy clothing stores.

He throttled on to Oakland with all its universities but the students were sleeping and the bike revved and swerved without command and Rig allowed the engine to steer him. He cranked the throttle then took his hands off the handlebars. He saw the Cathedral of Learning, a tower of dirty brown bricks and steps and steeple, like a church stacked on top of a church on top of twenty churches. Kids learned in there. They took classes. Rig was proud to have gotten his degree all those years ago, first in his family to graduate college, first in his family to play professional football. First in his family to make a million dollars.

How many families can say that?

He stopped for a second and considered his options, first being rehab, second being the Cathedral steps and his motorcycle, rubber on concrete, which seemed a more manageable choice than a counselor asking, “Why do you drink?” He held the clutch and backed his bike to the edge of the concrete, rear tire in the grass. He revved the engine. When life refuses to be challenging, you invent your own challenges. He stepped through the gears until the bike was in neutral. He took his helmet off and put it on backwards so he could only see darkness. It was not a comfortable feeling, blackness in your eyes, the engine in your ears, egging you on.

He took the helmet off and put it back on so he could see through the visor.

The Cathedral, churches stacked on churches.

Who the fuck thought that was a good idea?

He took his helmet off and put it back on, visor in the back, blindness up front.

You live to be great.

You have to live to be great.

And fuck it so he hit the throttle and popped the bike in gear and shifted again so his wheel popped off the ground as he raced forward and he leaned back and pretty soon the steps were underneath him, bouncing him skyward, bouncing him towards the landing by the main door, a place to park and reflect, to consider the accomplishment of racing blind on two wheels. No one had ever driven a motorcycle without sight up the steps of a college building and succeeded.

Then he wasn’t bouncing, he was flying, backwards or sideways or tumbling, the bike hit something, some beam or bench or ashtray made of stone, and Rig released the handlebars and gained more air and passed over the top railing of the Cathedral, one flight up, arms out, gravity gone, how he’d always wanted to feel, weightless, then back down to earth, to the fountain beneath the steps, water everywhere, blood in the water, Rig’s blood, most of it from his broken wrist where the bone pushed through, not that he noticed, exactly, it was a feeling, one of completion.

He did a hard thing: backwards helmet, concrete steps, still alive.

He woke up in an ambulance then again in the ICU with a tube up his nose.

That made the news.

That made all the papers.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.