Maryse Meijer’s The Seventh Mansion is the type of book that shouldn’t work, but somehow does. In fact, I’d call it one of the most bizarre, brilliant books I’ve read this year, and that’s saying a lot. This strange tale smashes together the holy and the earthly, the dirty and the sublime, the supernatural and the all-too real, all while exploring what it means to be human in a world that moves farther away from itself, from its roots, every day.

Xie is a fifteen-year-old vegan who moves from his home in California to a small town n the South to live with his father. He’s a perennial outsider wrapped in a hoodie regardless of the temperature, but he manages to make two friends, Jo and Leni, both of whom share Xie’s passion for animal rights and environmental issues. One night, they decide to free captive mink from a local farm, and Xie is the only one that gets caught. He get kicked out of high school and soon finds himself alone and depressed, so he starts spending more time in the woods behind his house and starts attending activist meetings with Jo and Leni. While in the woods, Xie discovers an empty church that houses the relic of saint Pancratius. The skeleton and it’s armor captivate Xie and he keeps going back to visit the remains. However, the visit stop being enough and he decides to steals the skeleton and hide it in his attic bedroom. Xie soon develops an emotional and physical relationship with the bones and spirit of the young saint, whom he calls P. As Xie’s relationship with P. becomes deeper and more complicated, so does the rest of his life. Amidst the chaos, and while battling hormones, discontent, and depression, Xie must learn to find balance between the reality around him and his extreme ideals of environmental responsibility, friendship, family, and purity.

The Seventh Mansion is a quick read, but not because it’s a short book or an easy read. There are no chapters and the text is presented in blocks with the dialogue built into the passages. However, the speed of the narrative has nothing to do with this. Instead, it comes from Meijer’s economy of language. There isn’t a single extra word here, and that’s hard to do. From the opening page, every line sums up an event, a feeling, a conversation, or a place without dwelling on unnecessary details. The author knows weirdness abounds, but she doesn’t stop to point it out, choosing instead to deliver conversations about environmental issues and sex scenes between Xie and P.’s bones with the same speed. This economy of language demands fast reading and pushes the narrative forward at breakneck speed:

Not a dream. His voice. From above, from below. Xie jerks back, staring. The face in the case the same, the body the same, not moving but something is moving. Inside and out. The sudden heat, the smell of bone, of earth, the stone, the moon against the window, and P. like all these things; a fact. Xie turns his back to the body, palms to his eyes, panting.

There are plenty of strange events in this novel, and Xie’s relationship with P. is the biggest one. Xie’s “beloved” is a refuge, an escape, and everything Xie has ever desired wrapped into one. The crumbling of Xie’s life and the blossoming of his relationship with P. are simultaneous events, and the power of the supernatural presence in Xie’s life understandably overpowers everything else. The result is, not surprisingly, empathy. As readers follow Xie and P., judgment and even shock fade away because we quickly understand the circumstances that lead to it.

There are a few technical elements at play here that shouldn’t work and yet somehow do. For example, the punctuation is unique. Every pause is marked by a period, including some commas and places where an ellipsis, a colon, or an em dash would’ve done a better job. It takes a few pages to get used to it, but then it starts making sense and fits well with the pacing of the story. Also, the narrative slips into second person from time to time. The reader is pulled into the story without warning. It is a jarring shift, but one that, over time, serves to increase the impact of some of the passages:

Long dream of the body, of that space between rib cage and spine, slightly electric when you enter it, feeling the bones from the inside; it always makes you come.

We often talk about brave, unique fiction, but explaining what it looks like is tough. The Seventh Mansion makes this task easier: unique, bold fiction looks like this. It is weird and deep. It inhabits an interstitial space between the humdrum sadness of reality and the magical spaces in which the impossible becomes real. The Seventh Mansion is the resulting explosion of the unholy crashing against the divine, and that makes it a book fans of great fiction should not skip.

***

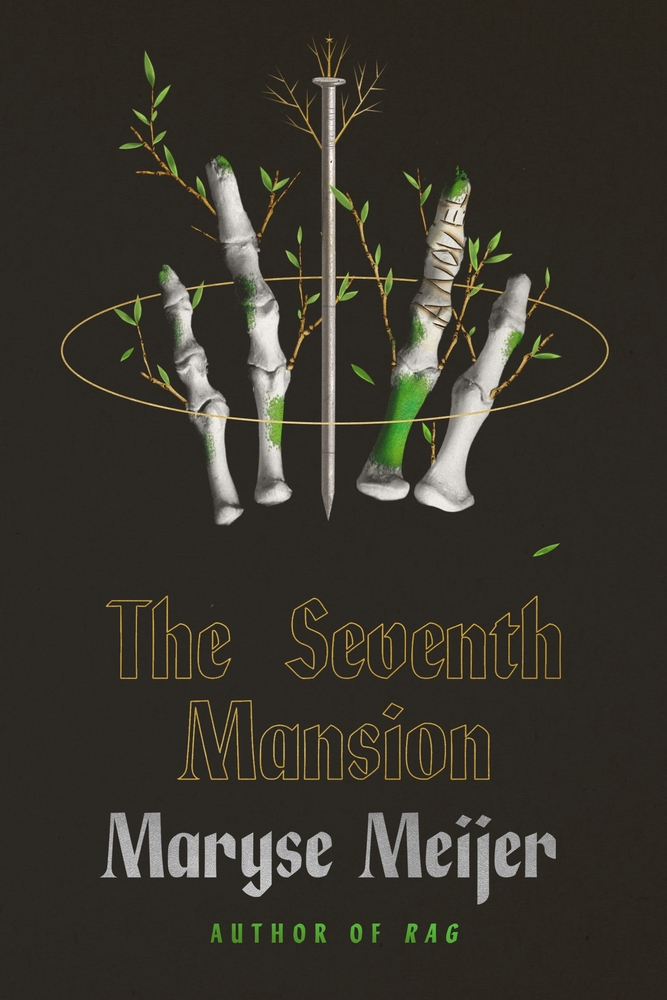

The Seventh Mansion

by Maryse Meijer

FSG Originals; 192 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.