There are a lot of things I like about Something Gross. I want to point out some sections in the novel I like and talk about why I like them and maybe what that means in a bigger way, outside of myself and the novel. Maybe what those parts of the novel mean for writing in general too. You know. A review.

I was excited about this book for a lot of reasons. It was a surprise and it was a novel and relatively lengthy. Over 200 pages. I didn’t know what the book was about except Big Bruiser Dope Boy (BBDB) wrote it and I appreciate BBDB as a writer.

When flipping through the pages of the novel, it appears more like poetry than prose. There are only four large blocks of prose in this novel. Those blocks are texts and emails sent by the narrator Ben to his boyfriend and eventual ex-boyfriend Ryan, and one block of prose about the repetitive ways Ben attempts to forget Ryan (fucking other people).

BBDB’s structure and action-forward prose is recognizable, and maybe something you’ve seen other writers use. The narrator talks about what he does. What he says. What others say to him. It is the type of writing that feels comfortable in this type of novel. There are riffs and jokes in the text. There are comments on the action of the text. This is a traditional type of writing found in this type of novel, with BBDB’s own spin on it.

But BBDB’s play within this surprised me. He moves back and forth through time. He explains how Ben met characters and tells stories associated with them. He moves into the time of those stories and writes with the same action-forward prose. He isn’t tethered to the now in the way many indie lit novels are.

There is an eagerness to be understood. To be felt. To communicate not just the events of the novel, the voice of the prose, but the reality of the lives within the words. It’s full of real shit. And BBDB wants the reader to know it’s real. Wants the reader there, hurt and sick and fucked up too.

Comparing BBDB to Sam Pink seems like an indie lit pastime that I’m sure is both flattering and annoying. No writer wants to be another writer. No writer wants their self-expression to be seen as something that could have been expressed by another self. Friend or mentor or hero.

So, I’m going to talk about that comparison some more here.

The comparison makes sense on the surface. BBDB’s first book included an intro from Sam Pink. They both enjoy cartoon imagery in some form. Sam’s “the cartoon continues,” and BBDB’s Foghorn Leghorn Poems. They even look physically similar. Tall. Short dark hair. Dark facial hair.

With Something Gross, I think it’s easier to talk about the differences between BBDB and Sam Pink. And I think it’s necessary to do that as well. Because those differences matter for this type of writing in a larger context.

I think the difference is this:

Sam’s novels are otherworldly in their singular focus. They are narrated by calm goofy relaxed characters who see everyone and everything as a possibility for play. Your boss, coworkers, roommates, strangers on the street all want to yes and your riffs. Shit will work out as long as you keep cool and have some kind of mantra.

Sam’s books are hopeful and joyous celebrations of life. Through all garbage in the world of Sam Pink’s fiction, the people are there to make you forget the smell. Sam’s novels are important because they take place in spaces many writers, before his influence, would pass over. An entire Sam Pink short story or novel can happen in the same place another writer would say, “He went to work. He watched TV. He woke up. He went back to work.”

This review is about BBDB’s Something Gross, so I apologize for talking too much about another author. I brought up Sam’s writing because BBDB’s writing has been compared to it, and because talking about what Sam’s writing is can help explain what BBDB’s writing is.

I know there are more than two writers in the world. There are at least three writers in the world. What’s up. I’m number three.

BBDB’s novel is not about work and roommates and playing in the places people choose not to play. It is about relationships and consequences. It is about heartbreak. BBDB still incorporates similar kinds of fun. There are still jokes. There are still has some tight riffs.

In the second section of Something Gross, “The Road Trip with Joey,” Ben drives with his friend Joey to Wisconsin, then Chicago, then Sante Fe, then back to Colorado. Because this section of the novel is about Ben’s friends he’s known for a while, there are stories about how they met. What their relationship is like, what their dynamic is. What Ben’s world is outside of Colorado.

We meet Norm and Nicola. Seamus and Lance. We meet Dr. Dean Campbell. We meet Dinah and her family in Wisconsin. We meet Ben’s mother and grandmother.

The jumps in time in this section stood out to me. The way BBDB smoothly moved from past to present in the same narrative. It’s not that this is an unheard of technique, it’s that it’s something many writers don’t do when using straight-forward action-based sentences. Often those narrators have no past. They only experience the present.

Ben has a past.

On page 22:

Joey and I drove to Dr. Evermore’s Sculpture Park outside Baraboo, where my grandmother was originally from

She came from a circus family

There was someone, a great aunt or someone, who used to hang by her long hair from the big top’s apex and twirl around

The park was tricky to find, tucked behind a salvage yard, but we found it

…

Dr. Evermore was the fictive artist persona of Tom Every

A Victorian inventor

Per the legend Every created, Dr. Evermore built The Forevertron to blast himself into the cosmos “on a magnetic lightning force beam”

To ride a rainbow road for eternity?

It was too much

There were giant mechanical insects

There was also an area of the park with an orchestra of birds

This is just a small example of what I mean. There are longer flash backs about Peaches, Ben’s ex, and Dinah, Ben’s older friend from Wisconsin. Flash backs to how Ben and Joey met, how they almost or briefly kissed once at a party.

I like these moments because they’re stories inside stories. They’re context to make these characters feel more real, more human. These stories are what make Ben’s journey matter. They let the reader know everything is important, before and after. The present moment is only for the reader, presently experiencing the book.

Ben searches and hurts in Something Gross. He hasn’t found a mantra yet. He doesn’t always keep his cool. This novel is about Ben’s attempts and his failures. His relationship’s failure. His attempts to communicate and the failure of those communications.

The novel’s strength is in how it shows those attempts and failures.

I think that’s the biggest difference between this book and the indie writing that might have influenced it. This book is about feeling outside of some normal track of existence. It’s about the small niche world of writers who use Twitter. But it’s more about a search for understanding that.

Yes, I’m aloof and sad and feel like an asshole shithead. Yes, I spend most of my time working and getting high and fucking, but everyone does that, right? Don’t you? Isn’t this normal? What about this is normal?

It’s a plea for someone to recognize of the complexity of that detachment.

The desire, in Something Gross, to connect with the reader sets this novel apart for me. All writing, all good writing, seeks connection. But BBDB has his own simple and human way of connecting that floored me.

I am telling you what he told me

This line is used for the first time on page 95.

It’s a line that some might argue is redundant. We’re reading the book. Of course, the writer is telling the events of the book. But it breaks the fourth wall in just the right way, at just the right time, in a necessary gesture of connection.

Yes, this happened. Yes, this is what was said. What else can I do but tell it?

“You” become a part of the story. “You” are the listener. “You” are the interlocutor of Something Gross in this moment.

On page 134:

We left the group and he told me he hooked up with a guy the last night of the cruise

“It just kind of fell into my lap – he was at dinner with Paul and me”

I told him that it was okay, that I had hooked up with someone while he was gone

“Okay, cool – wanna see a picture of him? – he was this black guy with a nine-inch dick”

I am telling you what he told me

You are given the conversation in the scene as it happened, and BBDB doubles down with this line, to elaborate Ben’s shock at Ryan.

Ryan is rude and exploitative. He is a handful of a person, as a friend and worse as a romantic partner. And just in case it isn’t obvious, you’re given the tag, “I am telling you what he told me,” to know he says some fucked up shit.

It’s amazing.

When I first read that line, I thought, “fuck yea, here we go,” the same way I would if someone said that line while telling a story to my face.

“For real?” I’d ask. And the other person would confirm, “for real.” It’s a type of doubling down that pulls the reader closer to the story.

The novel mattered most to me in the places it became more real. By real I mean moments that expose the characters’ interior thoughts and motivations.

This isn’t the first novel to delve into a character’s interior world, obviously. But I won’t say something like, “all good novels do that,” either. Indie lit novels often challenge this. They show emotions through images. Objective correlative is the name of the indie lit game.

I’m not pissed, I’m imagining my hand as a scythe cutting down anyone in a business suit on my commute to work.

I’m not in love, I am inventing a shrink ray powerful enough to make me microscopic and scientists are putting me into a syringe and injecting me into your blood stream, baby. I’m your disease now. Deal with it.

That shit is so good. It’s my bread and butter. And it’s useful. It illustrates the giant gulf between the things we feel and the things we say.

“Angry” or “enamored,” as words, are human creations. They’re just evolving linguistic placeholders for the way our insides feel. Who’s to say they’re more exact words than my scythe or the syringe full of tiny me?

Those gestures and images are in Something Gross for sure. They show up in “The Road Trip with Joey,” when Ben’s shit-talking and riffs take the place of him saying something boring like, “I didn’t like this guy,” or “We had fun conversations,” but they fall away in the sections that primarily concern Ryan.

In these sections, objective correlative wouldn’t be enough. The metaphor of emotion is great for poetry, but sometimes it has to be replaced with more. Something powerful and direct.

The text messages and emails are very important to this novel. They’re formatted differently. The voice is different. The information comments on the action of the novel. They provide a door into the emotions of the characters in a way that’s both obvious and experimental in its honesty.

This is a book about a rocky relationship. The characters have smart phones. They’re going to text each other when things are too rocky to speak face to face. Obviously. But, like the repeated line, “I am telling you what he told me,” these texts and emails break the fourth wall of the novel.

Ben is again in front of you pleading to be understood. He’s not summarizing a text he sent his ex. He’s taking out his phone and letting you read it yourself. Because it’s more accurate information. Because maybe you will understand the story more if you read the primary source.

The voice in the messages is hurt and trying to explain that. It’s a voice that’s still in the emotional moment of the story.

There are two text messages and one email in this novel. All deal with an argument the reader first encounters in the narrative of the novel.

From the first text on page 88:

No, I think I’d feel grateful and lucky to be a friend to you. But man, I didn’t know until I thought about what you said and how it made me feel that I have developed an intimate regard for you to the degree that your rhetorical (and yeah patronizing, but I don’t think that’s bad or wrong necessarily: people patronize/ condescend to each other all the time – it’s fine and it maybe even serves some greater societal function (?) – maybe I’ll get to patronize you someday… if I’m not doing it right now) preclusion of the possibility of what I’ll call a “relatively longer-term relationship” was a bit of a sheepish bummer.

Compare this to other parts of the novel. These are long, multi-clause sentences with bigger words, parentheticals, an energy coming from a heightened emotional moment. These are a look inside the voice of Ben.

Here BBDB lets go of narrative control. The text message reveals the weight of a scene, only a few pages before, when Ben and Ryan talk at Denver Pride. They zoom in on what Ryan’s words meant to Ben.

These messages are more sincere attempts at communicating Ben’s emotions and they are both successes and failures.

They succeed in showing the interior of a narrator, a narrator we’ve learned about primarily from his own storytelling voice. A voice with just a little more distance. The voice meant for the reader not the voice meant for Ryan.

They fail in showing Ryan how deeply Ben loves him. And by the end of the novel, Ben leaves Colorado for Wisconsin. He returns home to be closer to his sick mother.

And maybe that isn’t exactly a failure. It’s Ben learning what is most important to him. It’s moving away from what seems hopeless toward something that might, hopefully, bring some joy.

The novel ends on an image of a pair of cranes Ben has seen for years near his grandparents’ house. There have only ever been two cranes, but this time, the time of the epilogue, there is a third smaller crane. A child crane.

An image of hope.

A new creation that could more accurately mean “hope.”

This is a good book. I have more thoughts, but this is long enough already. If you ever want to talk about Something Gross, just let me know. Or, you know. Read it yourself. Think about it yourself. Maybe you’ll think something good too.

***

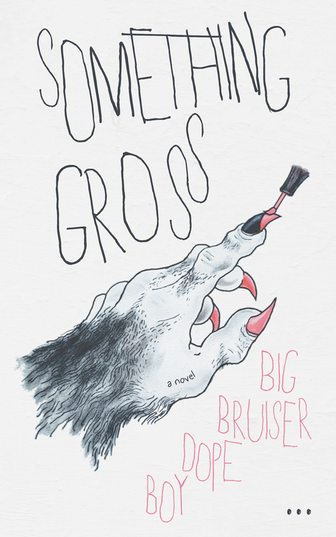

Something Gross

by Big Bruiser Dope Boy

Apocalypse Party; 248 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.