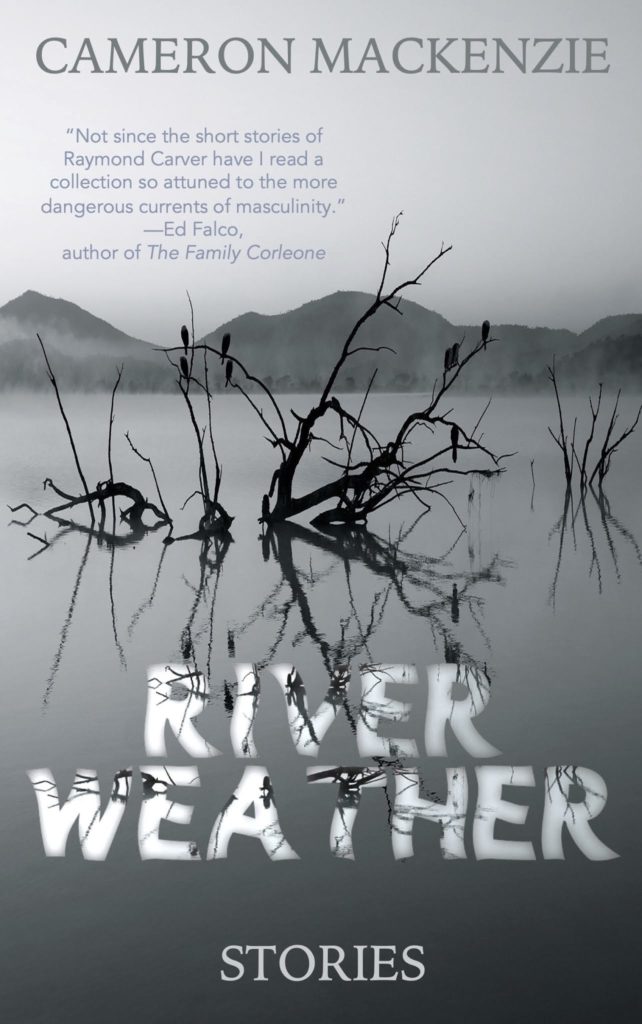

We’re pleased to present an excerpt from Cameron MacKenzie’s River Weather, a collection of short stories set against a backdrop of suburban sprawl in the Washington, DC area. MacKenzie’s fiction has prompted comparisons to that of Chuck Palahniuk and Raymond Carver; read on to explore one of the stories you’ll find in the new book.

***

Rowdy

(first published in Painted Bride Quarterly, May 2019)

It had only been three days since the baby had been sick. Three days since Julie had come into the living room where Jimmy had been flipping through his phone, looking at news, pictures, nothing.

“He’s burning up,” she’d said.

“Burning up?”

“Like a furnace.”

“Ok.” Jimmy had stood and followed his wife back into the darkness of the house and down the hallway, not knowing exactly what a furnace was supposed to feel like. Nor did he recognize the white pocket of fear that had begun to open up in his chest like water boiling in a pot.

When he’d held his son in his hands it wasn’t like he was holding his son but was holding instead a small and child-shaped piece of iron pulled glowing from a forge. The baby was shaking with the effort of its screams and Jimmy was suddenly, senselessly furious at his wife. He looked at the child, at the silhouette of the child in the half-light of the room. His wife stood mutely beside him as though he knew what had to be done, and Jimmy knew that in truth she didn’t believe he knew what had to be done, but he also knew that she hoped against all hope that he would know or would pretend to know, and so he pretended to know.

“Let’s get him into the bath.”

“The bath,” she said.

“Run the water cold,” Jimmy said.

He had heard of this, or read about it or seen it in a headline from a website for an article he didn’t read. Suddenly he was sitting in the white light of the bathroom, a bathroom with its little plastic toys now worthless and hateful and the limp washrags on the side of the basin and all of it lit up like an operating room, his son screaming and purple in his hands, shaking in the clear cold water like a motor inside of him was knocking against his skin. The pealing screams sliced down into Jimmy’s brain and he held his boy in the white and churning water, cupping his hand in the cold and splashing it on the baby’s back while his wife knelt behind him on the bathmat, her back straight and her hands on her thighs as the water roared from the tap until eventually, finally, the child underneath Jimmy’s hands began to cool.

Tonight Jeb was just a little fussy—a few wheezes, a little rattle. It was as though the bathtub had never happened, and for the child perhaps it hadn’t, but for whatever reason Julie hadn’t been able to put the boy down since. She had lost her confidence somewhere and the odd kick or squeal dispirited her, preventing her from seeing the rituals through. Jimmy took the baby from her, still a little warm but nothing serious, and he sat back in the rocking chair.

Before the baby came, Jimmy thought he was pretty good with song lyrics. He thought he knew entire albums front to back, albums he had listened to for decades. What he discovered when he sat down to sing those songs was that he couldn’t remember how any of them began. They all seemed to start in the middle somewhere and peter out after the chorus. Most nights he’d settle on Springsteen’s Tunnel of Love, side B, but could recall, at best, half of the melodies, only one of the bridges. He ended up humming the same sixteen bars over and over but, still imagining himself a musical savant, Jimmy began to jazz it up a bit. He’d lag behind the beat, he’d add a few notes. If he were feeling particularly confident he would, at times, build a new harmony overtop the first few he’d laid down. Tonight it was all of the above, the Stagg singing in his head until Jimmy convinced himself that he’d chosen the wrong career (such as it was), and was in actuality a natural musician, his gift in total atrophy other than these nighttime performances that were, perhaps, of some real worth. And if that were so, then so was he—that is, a man of worth. A man of value, a man doing good and useful work. After about fifteen minutes the boy was snoring in his arms, and Jimmy laid him back into the crib.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.