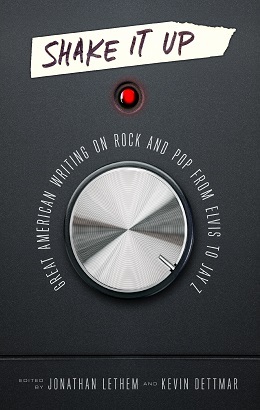

The nature of music writing over the years is one of constant change and evolution, one which the anthology Shake It Up: Great American Writing on Rock and Pop from Elvis to Jay-Z seems uniquely able to document. Editors Jonathan Lethem and Kevin Dettmar begin their introduction with a statement of purpose: “Fifty selections from fifty writers covering approximately fifty years of American rock and pop writing: it’s an elegant conceit, you’ve got to admit.” But a closer look at the work included in the anthology also tells a second story–one about how music has been and continues to be written about, and how music writing has evolved over the years.

That evolution is still ongoing: Pitchfork was purchased by Condé Nast in 2015; a recent piece for Bloomberg looked at how the sale had (or, in this case, hadn’t) affected the writing they published. And in a widely circulated essay, outgoing Guardian music editor Michael Hann wrote about what he’d learned from his experience and where he felt that music writing was headed. “Reviews, now, serve the music industry more than they serve readers,” he wrote. “Their main purpose, so far as I can tell, is to provide star ratings for press advertisements and to enable artist managers to feel content their client is getting coverage. But music writing itself, I think, is in good health.”

Shake It Up’s overarching story is about the evolution of rock and pop music over several decades, as it slowly amasses a sense of history. But the places where the pieces that it contains first appeared tell another story that parallels that one. In a 2011 review of collections of music writing by Ellen Willis and Paul Nelson, legendary critic Robert Christgau wrote that “’70s rockmags and alternaweeklies generated a lost trove of American criticism.” Willis, Nelson, and Christgau are all represented in here, music writers from what’s considered to be a heyday of the form–along with others who got their start in the late 1960s or early 1970s, such as Greil Marcus, Lester Bangs, and Carola Dibbell.

Bearing out Christgau’s observation, a significant amount of the writing in the book does indeed come from alt-weeklies and publications such as Rolling Stone that are best-known for their coverage of music. The Village Voice is heavily represented here, and other notable works first appeared in L.A. Weekly and Punk Planet. But, as an industry, alt-weeklies have hit hard times in recent years, and one can make the argument after reading Shake It Up that they’ve lost their position as home to some of the nation’s most essential writing on the subject of music.

By the time a reader has reached the end of the book, with recent pieces by the likes of Luc Sante (on Bob Dylan), Hilton Als (on Michael Jackson), John Jeremiah Sullivan (on Axl Rose), and Kelefa Sanneh (on Jay-Z), they’re looking at essays that were first published in high-profile publications that cover a broader cultural spectrum: the Sante and Als pieces first appeared in The New York Review of Books, while Sullivan’s and Sanneh’s appeared in GQ and The New Yorker, respectively.

There are also several generational shifts to be found in the book: the authors of the earliest pieces in the book were born before World War II, including Nat Hentoff and Amiri Baraka, while the youngest writers with work in it are, as of the time of this writing, in their early forties. A quote from an excerpt in the anthology from Chuck Klosterman’s 2001 memoir Fargo Rock City tellingly explores this divide.

The problem with the current generation of rock academics is that they remember when rock music seemed new. It’s impossible for them to relate to those of us who have never known a world where rock’n’roll wasn’t everywhere, all the time.

Though even that has, arguably, changed with time. In Hann’s article for The Guardian, he argues that rock music has become “something fetishised by an older audience, but which has ceded its place at the centre of the pop-cultural conversation to other forms of music, ones less tied to a sense of history.” One can only imagine what a second volume of Shake It Up released fifty years from now might look like, or what stories might emerge from it. Sometimes the narratives told about the narratives told about music are as compelling as the stories of musicians’ rises, falls, and obsessions. The work contained in Shake It Up proves that both are true.

This first appeared at Signature Reads.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.