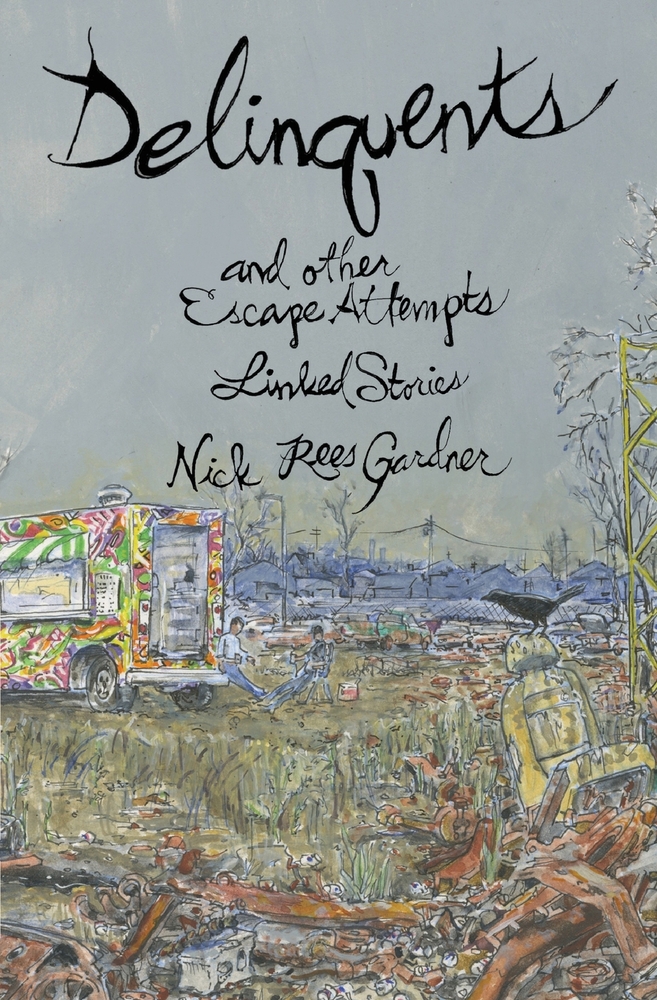

Nick Rees Gardner’s third book (So Marvelously Far, 2019 and Hurricane Trinity, 2023) is a linked story collection focusing on the fictional Westinghouse, Ohio. Right away, I was drawn to see Gardner’s world in connection with Sherwood Anderson’s linked stories in Winesburg, Ohio, and Gardner’s Delinquents didn’t disappoint. As the opening pages make clear, this Rust Belt collection is about a very different America than Anderson wrote about in Winesburg. They’re trapped; they’re often addicts; they’re seeking a means to escape Westinghouse; they’re looking to find love, meaning, connection, and some shred of satisfaction. Time passes or it doesn’t in Westinghouse, as the book points out. Too often, the characters struggle just to make it another day.