Memoryfoam

by Nicholas Bredie

I think I was against the memoryfoam from the start. The vaguely chemical smell. It was a smell I associated with my mother in black, drunk and surrounded by people. I know she is drunk because when I first got drunk I understood my mother as having been drunk at this moment she was wearing black. I try to place this association, asking my husband if he can help me place it. He shrugs a little, Sounds like something that might happen to a child. He’s loosened his tie, sitting in his navy socks and cuffed pants. What’s for dinner? He asks.

I was against the memoryfoam because we had a perfectly good mattress. A Perfect Sleeper. But my husband sleeps on his side. He said, Before we were married, I slept on my back. As if to say that it was not he or the mattress that was at fault. Sleeping on your side diminishes your sleep quality on a spring mattress.

The memoryfoam dealer’s suit was too big for him. It had a sheen that made it look expensive. My husband cast himself on the mattress in his wingtips. He said, Ahhh. I was caught up in the smell. I can’t recall what the smell evoked in the showroom but it wasn’t my mother in black, drunk. Something bad, but inarticulate. Doesn’t matter. Before I could voice it, my husband’s checkbook was out. As he sprawled on the bed he half wrote out his check, then looked expectant. The dealer looked expectant too. I started rummaging in my purse. I got no pleasure from the imitation leather grain that surrounded my checkbook. The dealer clicked a ballpoint and presented it to me as I drew the checkbook out of my bag. My husband finished writing out his check, flourishing his name as always.

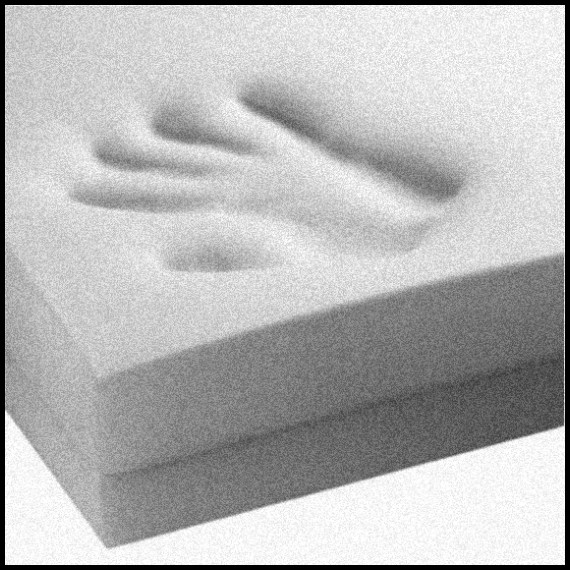

He insisted that we take the memoryfoam home ourselves. Pushing it up the stairs, I realized its density. Its pliant inertia. When we rested it on the steps, it deformed to their angles. This amenability pleased my husband, but it made it harder to push up the stairs. It made it into its proper position, onto the bedframe with no headboard. The Perfect Sleeper propped up, blocking the panoramic acrylic of San Francisco that we woke up to. The little red streetcar cresting the hill.

The first night I spent on the memoryfoam I didn’t really go to sleep. My body passed off, finding its place in the foam. But my mind floated above, as fully there as before. I went over the day’s occurrences: the purchase of the mattress, the expense, the effect it might have on a frock I had wanted to buy, the frock which had reminded me of a frock I owned in college that my roommate borrowed and never returned, the same roommate who had intercepted my then boyfriend as he returned from the hall bathroom and convinced him to take a drive with her that turned into a tri-state 7-11 robbery spree ending in Mexico I believe, while I tried to look comfortably seductive on my twin bed. As I thought this, I was aware of the mattress’ density giving way to my body. I went back to thinking about the cost of the mattress, the state of our finances in general. The state was good, I had to admit. As long as we didn’t total the car we could keep eating salmon steaks in teriyaki glaze with haricots verts and chardonnay. I associate this meal with silence. My husband likes eating in his socks. That way he can indulge his restless leg.

I told my therapist all this in the following days. It was much clearer with her. As it always is. I told her I was asleep but not asleep. She said I was worried that I couldn’t get pregnant. Then she checked something on her clipboard. Any questions? I said I didn’t think so. She billed me for the hour.

But the mattress operated as it was meant. Each night, the mattress was all the more ready for my form, its topology fitting with my contours. My dreams took on a fluidity without losing their value as dreams. That’s what my therapist said. I’d find my niche and then fall asleep immediately. My dreams were the opposite of my initial dreams, so good I felt like I was awake but dreaming. I dreamt about picnics I had with my husband before we were married. Beside an artificial lake that had formed in a gravel pit. And we had one of those perfect picnic baskets, everything perfectly integrated. And the ants crawling across my loose skirt. I’d wake up trying to wipe the mayonnaise from the edges of my mouth. Those picnics never happened, though there was a gravel pit a half-mile from my parent’s house. My therapist said, That’s how dreams work, when they’re working.

There was another dream I had, though it hardly makes sense: My mother and father had taken me out to a Christmas tree farm. They had tagged a tree in the fall. We had gone to see it as a sapling. Now the tree was a full-grown tree, a Douglas-fir. And we all went out on the lot to fetch it. My father rested the hatchet on his clavicle as we walked the rows. Rested it like a man who knew what he was doing, knew life from death, knew pruning and growing and cycles, with ease. These were not thoughts I had at the time. We came to our tree. My father asked my mother and I to step away as he set a notch in our tree. After the first stroke, I broke free of my mother and grasped his calf. Please, I said, don’t cut down the tree. He looked at me. I could tell he was going to explain something, but he didn’t. Instead, we all walked back to the lean-to. My father asked for a spade, a root knife, and a length of burlap. The pockmarked boy provided these things. Mother and I sat, drinking ciders she bought, and soon the tree was out of the ground with its roots. My father bound it in burlap and threw it over his shoulder. That Christmas I ran down the stairs. Then I ran through the living room, through the porch, through the porch doors and out in to the Virginia slush where my parents were, gathered around the tree they had transplanted into our small yard. It doesn’t seem real, I’d tell my therapist. She’d say, It probably isn’t. You’re just worried about getting pregnant.

We have dual sinks. My husband and I were brushing our teeth with our sonic toothbrushes. We did this together. After we got the bed and it learned my contours, he said, Wasn’t it worth it? I said, Yes, and spat. He said, I’m glad you like it. He went to put on his boxers and office socks. As much as he had espoused the memoryfoam, he didn’t seem any the better rested for it. His sleep quality had not improved. He still seemed fatigued in the mornings, and in the evenings as he loosened his tie. I suggested that he might take the tie off, now that he was home. The memoryfoam relaxed me, had relaxed me so I might suggest something like that. He just looked confused. I went to the kitchen and turned off the heat on the salmon.

It was a few months after the memoryfoam had taken to my contours that my husband asked to switch sides. He was standing above his sink, using his electric gum massager, when he paused, spat, and said, We should switch sides. I wondered at this, and finishing with my molars, and my customary mouth rinse, asked why. He said it was something good for the mattress. I said that I thought it grew accustomed to the person occupying the space, so switching was stupid. He spat some blood out, from his gums. He said, Yes, but you don’t want it to be too used to you. I didn’t understand that. But he said it, his gums bleeding, in that way that I knew would lead to a fight. I said sure, and that night we switched.

As I awoke the next morning, I could tell my sleep quality had been diminished. I wish I could have remembered that initial dream or any dream; the first dream that came to me as I tried to find my place in the divets my husband had formed. I felt an absence: he is larger than I am. I could feel the foam slowly trying to fill the absence, like how a region decimated by a plague gradually repopulates itself over several inbred generations.

I’d awake in sweats. I was glad I had started wearing pajamas a few years earlier. They were the kind of sweats that could ruin a whole sheet set. I’d awake with my pajamas clinging to my body in the bottom of the memoryfoam depression my husband had formed. I’d cast off those pajamas and take a crisp pair off the dresser shelf. I could feel my sleep quality diminishing. It was a problem I’d never had before.

I’d keep coming back to one dream once I’d settled into my new side. It was a dream of my mother in black, drunk, surrounded by men in suits. I’d try to make her match with the mother in the Christmas tree dream, and see her sipping cider sitting on a too small stump. But there are no Christmas trees around, only stumps. And she tosses back the cider and laughs a little to herself. And there are men with suits around her and she is laughing with them in spite of the smell, in spite of me on a stump just too far from her. The smell turns from pine to Pine-Sol. This was the dream I had on my new side of the memoryfoam, and I’d come back to it.

My husband and I were brushing our teeth at our sinks a few weeks after switching sides. I felt as if my sleep quality had been seriously diminished. My husband seemed chipper. My gums were bleeding. Oh, he said, Here, use my Sensodine. He then went over to the vanity mirror, pulled on an Oxford and flourished his tie on. As he inflected the dimple on his full-windsor, he said, You can always go back to bed.

I told my therapist that I was suddenly afraid of death. She laughed and billed me for the hour. My gums seriously deteriorated. I couldn’t eat apples anymore without leaving the white pores of the fruit stained red. My husband had taken to walking around the house in his work socks humming Bing Crosby Christmas songs. I could feel the memoryfoam gradually reaching for my contours at night. As it did so, the image of my mother in black, and the smell, became clearer. The smell was chemical: My mother is wearing black, I’ve turned to see her. From what, I’m unsure, but that is the source of the smell. She is laughing, and it fills me with hatred. She is laughing as three men in suits stand around her shaking form. They are awkward, shifting their weight, but also oddly eager. My mother’s gestures are comically large, the black she is wearing has moved, in that multistable manner, from demure to fuckable. I can’t believe I’m dreaming this about my mother. You’re afraid of getting pregnant, my therapist says, and bills me for the hour.

Gradually this has faded. I still see it in dreams, occasionally, the hyena laugh affixed to my mother. My mother pushing me on swings, my mother at my high school graduation, my mother sitting and watching my father sink his spade into the sod around the Christmas tree. And it becomes more and more impossible for her to cast her head back in that manner, as the foam begins to meet my flesh. I still catch a whiff of those memoryfoam chemicals that send the image of my drunk mother in black through me like I stuck a finger in an outlet. My husband’s sleep has become more troubled. His gums have begun bleeding again. As we sit down for Mahi-Mahi in pineapple salsa, I have seen his leg bounce uncontrollably. We’ve switched to Mahi-Mahi because it is more healthy than Salmon. As we walk into the bathroom to brush our teeth, I feel the question come on. My husband turns to me and mutters. I say, I can’t hear you, embracing the way the electric toothbrush causes my whole skull to vibrate. He spits bright red into his sink. He gargles, then spits red water into his sink. I watch his teeth, the strong outline of red forming along the edge of his gums, along his lower canines. He says, We should switch sides.

Nicholas Bredie graduated from Brown’s Literary Arts Program. His writing has appeared in The Believer, The Brooklyn Rail, The Fairy Tale Review, Opium, Puerto del Sol and elsewhere. With Joanna Howard, he is the co-translator of Frédéric Boyer’s novella Cows, published by Noemi press, Summer 2014. He lives in Los Angeles.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.