Kiddie Ride

by Jackie Corley

The Plymouth turned a corner onto Beachway Avenue. Eric felt Keansburg closing in around him when he wandered into this part of town at night. The stunted amusement park on the bay side, a block of water rides on the other—it had a tunneling effect, especially from a car. Drivers took the narrow road too fast along the curve.

Any upstanding citizen abandoned the northern tip of town after sunset, but you could spot the occasional junkie or hustler or lost drunk hugging the locked walls of the arcades. Eric had been all of these. He’d been king of all these. But that upstanding citizen bit—that was some other lifetime ago, wasn’t it?

“Brilliant idea number three-thousand-forty-seven: Keansburg car trip bingo,” Eric said.

He was in the backseat of Steve and Connie’s van as Steve drove. Eric had represented them in the civil suits they brought after minor car accidents. He made them bank, too, and won Steve a permanent disability claim. But that was the other lifetime ago. Now Eric spent hours looking at Steve’s bald spot and the white roots of Connie’s frizzy hair, dyed bozo the clown red.

“G-five, players. We have a G-five. Homeless guy nodding off on a fence. Do I have a bingo?” he said. Eric slid open the door of the moving van and underhanded a full beer can toward the man. “Drinks are on Jesus.”

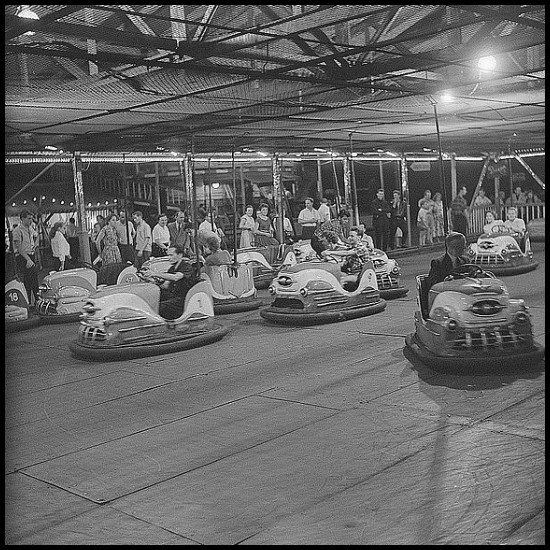

Steve pulled the small king back by his t-shirt. A bumper car appeared in the roadway and the Plymouth swerved around it. The van door closed with the momentum.

“They should’ve cleaned those up already,” Connie said. “They do all this talking about the storm and it’s been months and nobody’s done a damn thing.”

Sandy: one month and seventeen days, Eric thought. He didn’t have a particular reason for counting. He didn’t have a particular reason to care. He had walked around Keansburg in a bathrobe and jeans when the rain started. He returned to Steve and Connie’s house before nightfall, before the bay broke over the berms and joined the sudden river coursing down the road. Water pushed arcade games and the bumper car fleet onto Beachway. Fiends scavenged for change the next morning until patrol cars chased them away.

“Nothing else on the road,” Steve said.

Keansburg had been a resort town decades ago. New Yorkers flocked across the bay in summer, Eric’s family among them. A different hundred-year storm washed out the north of town in the 1960s, but Eric’s people returned. He was born eight weeks early in July, ushered in by firecrackers; his first crib was in one of these bungalows. Eric’s father brought them back to Brooklyn after Labor Day and never discussed the stigma of his New Jersey birth, even after the family permanently settled in the state.

Eric didn’t consider himself rooted to this land. The family abandoned it for a Spring Lake beach club membership when he was a toddler. He didn’t ascribe to a Keansburg mythos the way his uncles and older cousins did. His childhood summers didn’t include skee ball or ferris wheels or liter cups of greasy fries. He didn’t mourn the charred remains of the bowling alley or the dance hall and the Casino Movie Theater that burned with it. When he tallied the Keansburg drug offenses and petty thefts in the police blotter, he was casually embarrassed and then he forgot.

Eric only considered fate—that his misfortune was somehow tied to the town’s—after he blew up his career and marriage a few years ago. Eric found that particular implosion quaint compared to the failed attempt at resurrection that followed. There was an ellipsis between then and now; it held live current.

The Plymouth turned into the apartment complex off Belleview and Steve had his hand in front of Eric before he put the car in park.

“You like the way my money feels.” Eric ignored the hand and flicked twenty-dollar bills onto the floor.

Connie slipped a swollen foot out of her sandal and snatched bills with her toes as Steve collected the rest. They argued about the money, about how much Steve needed for the buy, about why Connie needed to hold any at all or had any right to it.

“How about groceries?” she asked. “You eat what I put in front of you, don’t you?”

Steve shook a soiled McDonald’s bag at her. “When do you cook? When do you go to the store?”

This is what counts as amusement, Eric thought. And when the distraction grew tiresome, he kicked the driver’s chair and Steve ran from the car.

The apartment buildings looked like barracks. Long brick walls and tiny windows. One unit had rows and rows of Christmas lights duct-taped across the glass like blinds. The other apartments were dark. Most first floor units had flooded out and been abandoned after the storm, but there was life here still, either sleeping or in hiding. Eric wondered how many remained or set up squats. Cheapest million-dollar ocean views around.

Travel up and down the East Coast and you find the money along the water, but not here, he thought; some trick of history kept this place fit for clamdiggers only.

When Eric was still playing politics—running for freeholder, running for assembly, filling whatever slot on the ticket the party needed a sacrificial lamb for—the back room talk always turned to prospecting. Where was the next land grab? Where could you make big money on redevelopment? Luxury condominiums sprouted ten-, twenty-story high on the footprint of torn-down bungalows in Long Branch and Asbury Park. Eric always thought the Bayshore towns like Keansburg were primed if you could get a rainmaker on council or at least somebody who wasn’t a yokel.

These conversations didn’t come up in the current iteration of Eric.

Life in Keansburg had the advantage of being casually familiar without holding any totems of his past. There was no custom-built, 2,500-square-foot home housing ex-wife and child to pass on the way to work, no apartment where Victoria’s Secret catalogues arrived in his ex-girlfriend’s name.

Connie started a cigarette. When the cheap lighter clicked, his legs cramped and his wrist stung at the pulse as if the blood was scratching its way out. He slid the van door open and kicked as he marched into the parking lot.

“Where you going?”

“Pavlov’s dog,” Eric said.

“Whose dog? You talk nonsense half the time, I swear,” Connie said.

He took a lap of the parking lot but it didn’t move time or Steve any faster. Supply dried up in the weeks after the storm. Their regular dealer lost his house and holed up in the emergency shelter at the middle school before moving in with cousins in South Jersey. This Belleview channel was a new discovery.

Eric strained to hear the bay as his wet breath rattled in the cold. He pulled his arms inside his t-shirt and stood underneath the window covered in Christmas lights.

He remembered decorating his own house with his son, Colin, the December before the divorce. He gave the boy an impossible knot of light strings to detangle and check for defects. Colin sat with his legs in a “W”—a little Buddha in reverse, Eric thought—and focused on the task for hours, which would have been a freakish notion for any other five-year-old but was typical of his son. Eric and his wife called the boy the Old Soul. They were both hyperactive and Type A, so this patient, sensitive child was a source of wonder. Eric remembered those tiny fingers navigating the threads and glass.

(He failed to recall how the rest of that day proceeded: he drank a screwdriver from his travel mug all morning, grew frustrated with the decorating process, and fell asleep on the couch. Colin strung up the lights with his mother instead.)

Eric considered the neat rows of lights on the Keansburg apartment window above him. There had to be dozens. A steady hand measured and positioned each one.

The window slid open an inch—as far as the network of lights would allow.

“Nobody wants you here.” A voice, smoky but feminine. “I’ve got kids in the other room and I’m calling the cops.”

“Nobody wants me here? I want me here,” Eric said. “You hear me? I want me here.”

Steve appeared, rounding a corner and charging at the noise. He wrapped his arms around Eric, who struggled, mummified in the shirt. Steve carried the shrieking figure to the van and tossed him inside, leaving Eric to flop around on the floor like a carp.

The Plymouth tore out onto Beachway. The entire patrol division in the one-square-mile town knew their car, knew their names. They were a block from Steve and Connie’s house when a police car turned in behind them with the roller bar flashing.

“Lure ‘em in, Connie. Hide your pit stains with your hands and lean forward,” Eric said.

“You keep entertaining yourself. I’m not even dealing with you,” she said.

The officers waved flashlights into the windshield to beckon the three of them out before they themselves stepped into the cold.

“You know the drill,” one cop said into the car speaker. “Line it up. Hands on the vehicle.”

They shuffled out of the van, jostling against one another like penguins, and spread their arms across the steaming hood. Eric came out clean during the pat down, but the officers found the crack Steve denied in his jean pocket.

“Wait, I have something in my shirt,” Connie volunteered. “You put down I’m a cooperating witness.” She snapped the elastic of her sweaty sports bra and folds of heroin fell out. (That the heroin existed at all was news to Steve and Eric. They would have to probe her later about where she acquired it.)

“CDS on Larry and Curly,” said the one officer, the talker. “Public intoxication on Moe?”

His partner pushed Eric’s torso onto the hood and cuffed the little king first.

The police station was housed inland—where the working class citizens lived and where their parents and grandparents had lived before them. And they were citizens in the truest sense: municipal meetings were standing room only and the fiery public comment portion could last hours. Politics was tribal in Keansburg, almost blood sport, and neighbors shunned neighbors for failing to attend an important planning board vote or cast a ballot in an election.

These tribes fell squarely on ethnic lines. When the Democrats had power, Main Street closed for a Columbus Day parade and when it was the Republicans’ turn, the town gathered on St. Patrick’s Day. The only mayor to keep a tenuous peace had an Italian name and an Irish mother.

The patrol unit waited on Steve and Connie’s county transfer car in the station parking lot. Eric traced stars into the window condensation with the tip of his nose. He started writing “Eric Lives,” but the car arrived for Steve and Connie before he could finish.

The chatty cop escorted Eric inside for paperwork. He provided his full name, date of birth, current address, and social security number as requested—and to avoid a charge of providing false information to an officer. However, the occupation question seemed to him to invite a level of creative freedom. Were they really going to add another count and additional paperwork because he claimed Jedi Knighthood or tenure as a longshoreman?

“And what’s our occupation today?” the officer asked.

“Tibetan monk,” Eric replied.

“Unemployed,” the officer said, scribbling onto the initial appearance warrant.

The officer brought Eric to the holding cell, where he sat on the floor alone with his t-shirt pulled over his knees.

In the civilian world, he contemplated the monastic life. He contemplated it often and aloud to anyone he cornered in a crowded room.

Those who heard tales of Eric’s monk cave included: his ex-wife; his son; his contractor; his chiropractor; the county Republican Party chairman; his running mate in every election; the paralegals at his former law firm; the call girls at the New Jersey League of Municipalities convention in Atlantic City from 2004 to 2009; his ex-girlfriend; and Connie and Steve.

The cell had cave-like qualities. It also smelled of urine, cheap cologne and bleach. The odor and the flicker of a dying fluorescent light bulb worked against the monastic fantasy, and he was grateful when the silent cop pulled him out for processing.

The police station was housed in an ancient building and, like many of the older homes and businesses in Keansburg, additions had been made over the years without thought to aesthetics or symmetry. The officer led him through a maze of fabricated walls and up one set of stairs and down another until they came to a room with a blue screen and a tripod.

“Do you know if I was smiling in the last one? I like to switch things up,” Eric said.

After several blinding flashes, the cop motioned with a swirl of a finger and Eric turned sideways.

The next morning he was RORed—released on his own recognizance—with a jacket from the police department’s charity bin and a court date set in the new year.

Eric hadn’t stood outside in daylight since Sandy. Keansburg had been overrun with police and politicians and National Guard and out of state utility workers and more layers of authority than Eric cared to know. He preferred Steve and Connie’s drafty, yet shockingly dry, split-level house, even in the dark weeks before something of the power grid had been restored.

Eric had a theoretical knowledge of the storm. He knew of Sandy in the same way he knew of wildfires in northern California or the Japan tsunami. He knew of it as a thing that existed in the world but not as a thing that existed in his world beyond a temporary lack of hot water and a choked off drug supply chain.

The wreckage of the sleepy, inland residential blocks startled him as he walked from the police station. Mounds of garbage lined streets from one end to the other like misplaced sand dunes. Power generators buzzed on lawns, which weren’t so much lawns anymore as uneven dirt patches. Telephone poles tilted precariously into the street with the frayed wires dangling below and the transformers that lit the sky green when they exploded with the storm surge scattered beneath.

Eric unlatched the gate to a front yard. (The remaining chain link fence was missing, but he entered through the front gate anyway.) He walked up the concrete steps and pretended to ring the bell to a home that had been demolished weeks before. A pantomime without an audience quickly bored him; he turned from the empty lot and surveyed the rest of the block.

An SUV with New York plates crept up from Main Street. A slack-jawed woman in the passenger’s seat wielded a camera phone as her husband pointed out collapsed buildings and homes off their foundation and bare foundations on otherwise vacant lots. A child popped out of the back seat and leaned forward, hugging the front headrests to get a look from his parents’ privileged vantage point.

An older woman watched the car as she smoked on her sunken porch and gripped work gloves. She cocked her head, debating on something. Then she ran into the street and waved the car over. She leaned inside the open driver’s side window, careful to hold the cigarette at a distance behind her.

“You need to leave. This isn’t a tourist attraction,” she said.

The shamed carload accelerated to the speed limit and drove out toward the highway.

The older woman remained in the street, staring at Eric. He hopped off the concrete steps and walked around the gate.

“This isn’t a tourist attraction,” she repeated.

He doubled back toward the shoreline, where the destruction didn’t seem like destruction at all but the festering of a long-open wound. The amusement park and the water rides looked stunted in daylight. Eric rifled through the broken arcade games and kiddie ride cars the town’s public works department had dumped in the beach parking lot. He robbed the machines of their prize tickets, which he draped around his neck. Eric twirled the ends of the ticket strings as he walked further down Beachway Avenue. The bumper car the Plymouth narrowly missed the night before had been flipped onto the sidewalk.

Eric dragged the bumper car into the middle of the road and sat inside. He vocalized the sound of a revving engine and worked an imaginary gear shift. Passing traffic gave him a wide berth as it went honking by, though he didn’t seem to notice. He stared down an endless, invisible racing strip and turned the wheel in to avoid unseen obstacles. He drove in place for an hour before the police came back for him.

Jackie Corley is the founder and publisher of Word Riot. Her work has appeared in Redivider, Fourteen Hills, 3AM Magazine and in various print anthologies. A short story collection, The Suburban Swindle, was published in 2008 by the now-defunct So New Press.

Image: Deutsche Fotothek via Creative Commons.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.