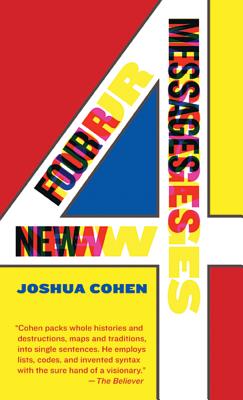

Four New Messages

by Joshua Cohen

Graywolf Press; 208 p.

I hesitate to say anything concrete about Joshua Cohen’s new book of somewhat short stories. 4 New Messages contains four new stories that require more than a thorough first read. In fact like many other dense, complex, even avant-garde authors, Cohen’s new book requires numerous readings simply to pin down the plot before we can even discuss his novel use of language or the larger themes and value of this book.

In that sense, certain authors need to build our trust. We need to believe that the author will not just show off their intellectual prowess, or will not lead on us a path of narratives within narratives just to find out that we’ve started again at the beginning, a sort of literary riddle. Based on his previous work, I trust Joshua Cohen. But his new book deserves some sort of warning sticker: “Not for the easily distracted or for those seeking light and quick consumption.” This book requires a quiet room, a ready mind, and a pen to track different threads of stories, to underline words that require a dictionary, and to add statements of wonder beside the sentences Cohen pulls off.

Despite the complexity of each story, finding commonalities among the quartet presents a much easier challenge. All four of these stories flow from the voice of writers–mostly struggling ones–as they tell another person’s story. In each story, Cohen builds a narrative within a narrative, sometimes within another narrative. Like many a contemporary writer, Cohen acutely feels some of the absurdity that stems from our new technology, the whims of social media, and the blurring of reality and fantasy in both directions of which something like pornography creates. Cohen acutely observes many of the ridiculous situations that these fluid technologies create.

With an understanding of what unites these stories, we can celebrate that each the quartet finds Cohen in striking different tones. “Emission,” through a narrator who gave up writing to make his first million in business, tells the story of a young drug dealer with all the wrong personality traits for dealing blow: friendly, desperate for recognition and love, with no sense of intimidation who loses his identity in the tumult of internet gossip. (He apparently once masturbated over a sleeping woman at a party that he dealt coke to; classy, I know.) Mono, the dealer, unfortunately relates this story to a veteran blogger who opportunistically destroys Mono’s life and livelihood in that ferocious rush of information zooming across the system of pipes that is the Internet. Like all good bad criminals, he bungles through the attempts to silence this bane of his life, forcing him to leave for Berlin to start a new identity. This story, the collection’s funniest, doesn’t sacrifice any of the more heady ideas that permeate the background. It asks challenging questions about the nature of identity, the degradation of the Internet, and commoditization of art and writing; these are themes Cohen will return to throughout the collection.

In “McDonald’s,” the second story of the quartet, another struggling writer attempts to tell a fictional story through telling his own story of attempting to write this fictional story (it feels that winding reading the story itself) but finds himself blocked by his inability to use “McDonald’s” in his work. Though he knows that more celebrated and talented writers already dealt with all the ambivalence and knotty issues that blur advertisement and art, he still feels insecure and confused about their relationship. (Cue David Foster Wallace issues.) Written in a somewhat (I believe purposefully) dense style of purple prose, the author/narrator attempts to substitute compelling content for intellectual flair, all to no avail until he finally can name his predominant issue, an issue in line with Harold Bloom’s anxiety of influence and a Marxist allergy to the commercialization of Art.

The most accessible and moving of the bunch, “A College Borough,” finds Cohen at his best and most emotionally powerful. In this story Cohen creates a tension between a more cynical, jaded, accomplished New York Jewish author, and the more naive idealism of a midwestern college writing class. Relegated to the anonymity of the midwest, the New York writer compels his students to rebuild the Flatiron Building instead of submitting stories to workshop. Cohen, in a flair of genius, investigates the relationship between book and author and between reality and fiction as the teacher allots jobs based on what he perceives as lacking in his students literary styles, or as their strength. (If a student can do flash and style but fails at poignant interiority, he appoints them as an interior designer to counterbalance their natural tendencies.) In a humorous twist, this assignment moves each student past their hope of writing into the more concrete realms of contracting, managing, interior design and architecture. In a sense, Cohen plays a heartfelt joke on the nature of writing today as a monetized career. Writers, more and more, feel the need to justify their work, to explain its relevance, or to expound a grand theory of literature that solidifies its importance to a world increasingly commoditized. Cohen evinces a strong Hegelian sense of tension between the thesis and antithesis but with a more postmodern touch of a lack of synthesis.

Even as the story coheres emotionally, Cohen then masterfully undercuts it all (spoiler warning) through the shattering suicide of the beloved professor at the end of the construction of the building. Cohen evinces an ambivalence as to this gesture. He doesn’t deign to explain the suicide, but the narrator at the heart of the story feels angered and is forever wounded by this apparently narcissistic act.

The last story in the quartet, “Sent,” presents the greatest challenge to both the reader and a critic. Beginning in the world of myth and symbols, Cohen creates a folktale-influenced world in which the loss of religion and the fluctuations of literary theory take shape. (Example: a bed made of wood carved with a magical axe, where the representations on the headboard elicit a range of historical responses to art and to texts.) From there, Cohen tells the story of a struggling young journalist somewhat obsessed both with porn and the spirituality of pornography to the extent that he finds himself in a Russian town that harbors many of the women he watches in pornographic streams. This story, in contrast to the rest, left me feeling cold, distant, frustrated and sad, though not in a cathartic way.Yet, in that manner of trust we give to great writers, I hope to return to the book as a whole, but especially to this dense story that defies easy reading.

It’s good to be reminded of this power of literature once again. As a friend of mine noted, perhaps more than any other writer today, I find it exhilarating to watch the intellectual and emotional development of Cohen as a writer take place on the page. Though not a masterpiece, his most recent effort contains all the trappings of one: the density, the ingenuity with language, the ability to deal with the most exigent and yet universal of issues, and the playful desire to experiment. All of these make this a book to not only read, but to contend with.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google + and our Tumblr.