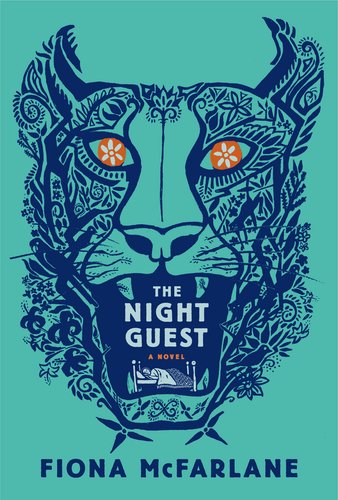

A month or so ago, I went to an event for the Sarah Weinman-edited anthology of domestic suspense, Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. (Which, by the way, is fantastic.) The event featured Weinman in conversation with Hilary Davidson, and among the topics that came up were the definition of domestic suspense, and the way that it, as a genre, has passed in and out of popularity. I found myself thinking about domestic suspense a lot when I read Fiona McFarlane’s The Night Guest. It’s a novel with a lot to admire, but certain elements got under my skin somewhat.

Much of the novel’s action is confined to a house near the beach in a small Australian town. It’s the home of Ruth, an elderly woman whose husband died some years earlier. Her children live far away, and she maintains a good, if sometimes tense, relationship with both. As the novel opens, she has a vision of a tiger in her house, and it’s unclear what this means: a premonition? A sign that her mind is slipping? Or is it meant more literally? Soon, a woman named Frida arrives, saying that she’s a caregiver sent by the government. Her initial visits are brief, but she convinces Ruth of her importance; soon, she’s spending more time there, accepting money from Ruth, and becoming more of a presence in the home. And, as Ruth begins to take care of herself less, her self-sufficiency slowly ebbs away as well. But throughout, there are hints that things may not be what they seem. Does Frida have an agenda of her own? Or is Ruth no longer a reliable judge of the events in her life?

There’s plenty to like in The Night Guest: an ably-paced, tense narrative of control; meditations on memory; and an excellent portrait of Ruth, whose childhood and roads not taken become essential components of the book. But the novel’s handling of race struck me, in parts, as problematic: Ruth spent part of her childhood on Fiji, and assumes Frida’s family hails from there as well. Unfortunately, this (to me) sometimes gave the impression of Frida as potentially sinister Other, and keeping the focus away from the power dynamic that fuels the novel’s most compelling aspects. It’s unclear if this is intended as a nod to Ruth’s childhood spent in a colonial system — that Frida’s appearance is a kind of reckoning. I don’t think that’s where McFarlane is going here; for all that the tiger that opens the novel has symbolic heft, this book’s concerns are largely realistic, and its language deeply physical. But the incorporation of race into the novel felt, to me, problematic rather than something that accentuated the gripping plot at its center.

***

In my ongoing quest to play catch-up with 2013’s acclaimed books, I read Adelle Waldman’s The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P. (Next week’s column will likely feature Tampa, Enon, and The Good Lord Bird.) I’d read Waldman’s novel back to back with Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, and the two books began oddly blending together in my mind. Given that Waldman’s book is a mannered study of Brooklyn writers, focusing in particular on a particularly self-obsessed one (the titular character), and VanderMeer’s focuses on an expedition sent to study an area where something uncanny has happened, this was not something I’d anticipated happening. And yet: both Waldman and VanderMeer absolutely nail emotionally remote intellectuals grappling with forces beyond their understanding: for Waldman’s Nathaniel P., the fact that he is, perhaps, not the greatest of boyfriends; for VanderMeer’s unnamed explorers, the conflicts and secret agendas within their group. And maybe that illustrates one larger point: whether you’re writing comedies of manners or surreal science fiction, having believable characters goes a long way. Waldman’s book felt spot-on and painfully honest; the way VanderMeer’s narrative grew steadily more tense and ominous

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.