Transcription

by Regan Mies

My mother told me over the phone that my brother had become “selectively deaf.” He could still hear. He enjoyed instrumental music. He often took nature walks in the arboretum along the shore. When we were kids, he could identify birds by their calls.

“He doesn’t want to listen to you?”

My mother scoffed. Her shopping cart clattered. The sound muffled as she swapped her phone from one ear to the other. “You know your brother. It’s his new thing.”

Matthew had always had fascinations that lasted a month or two, sometimes longer. He wore only white in tenth grade. There was the year he became nocturnal.

“I don’t get it.”

My mother inhaled. “He wears those Bluetooth things around people, so he can’t hear anything they say. They’re noise-cancelling now.”

I boarded the train when it arrived at my station. Conversation surrounded me. Mother to toddler in a teddy bear onesie: What did we talk about, I’m tired, sit down. Man on the phone with his partner: I swear to god, cross my heart, what do you want me to say.

My service crackled. My mother said, “He’s ‘taking control’ of the, ah, inputs? People, radio, the ads… you know.”

I wanted to sit; there were no open seats. I was annoyed. I was reluctantly curious. “Control how, though.”

“I don’t know, Kris. Content he takes in, things people to say to him—he emailed me, I’ll forward it to you—he wants everything in writing. To turn it into a work like he does. Paper bags—not plastic.”

I could hear the cashier swipe groceries on the opposite coast. “An essay?” I asked.

“I don’t know, honey, I can’t keep up.”

“Huh.”

“He’s transcribing everything into his own handwriting.”

I imagined the notebooks and loose scraps. His perfect, swooping scrawl. What would I say to him if I were forced to write it? Would I offer an iMessage, an email, a letter in an envelope?

How could someone crave artistic recognition with the unwavering intensity with which I sought total anonymity? Someone so close to me. So similar, so dissimilar.

Two peas in a pod, my mother used to say.

Yes, my father would agree. If one of them were a carrot.

Matthew might have responded, And if they hated each other, and I’d have stuck out my tongue or pouted or thrown a book.

“I’ve got to go, Kris,” my mother said. “I’m loading up the car. But you’ll write something to your brother? Humor him?”

I told her I’d consider it. She seemed satisfied when she hung up.

—

My brother has always been shamelessly over-confident, narcissistic in that way artists are when they’ve convinced themselves there’s nothing else they could do with their lives.

I could never admit my own desires to myself. Who was I to profess a higher calling, to declare myself too good for entry-level job applications?

My longing felt claustrophobic.

I thought about art, dreamed about it, but had nothing to say.

I can only admit any of this now because it’s all so far removed. Any window of time that might have once existed feels as though it closed years ago. Which is a weight off my shoulders. A decision made for me. A decision I’d managed to avoid my way out of.

—

I spent hours that week in front of my inbox. My laptop came into the kitchen. I set it on the counter when I cooked. I left it open on my bedspread. I clicked then closed New Email. My fingertips traced the keyboard without ever pressing down. The TV was often on and turned to the local news channel, where the newscaster said things like, A million pounds of ground beef recalled amid e. coli concerns, and the weatherwoman said, See tonight’s meteor shower through breaks in the cloud cover.

I wanted to ask Matthew whether he wore his noise-canceling headphones alone in his apartment. What happened when their charge ran out? What if he dreamed people talked to him?

And if I emailed, would my words be tied to my name? Or would he render them anonymous? Would he pull apart my message, separating sentence from sentence, word from word until I became something wholly abstract?

—

Hi Matthew, I began the email, which I sent late Sunday night, Monday morning. I had written the words, rewritten them, deleted them, and brought them back. What I came up with, in the end, felt unremarkable. I wrote, Mom told me about your transcription project––the headphones and the inputs and everything. I’ve been thinking about it a lot, all your art. I told her I’d be writing to you. I guess I’m wondering how you make it all work. Best, Kris.

—

I never keep the mail I receive. Not the drug store birthday cards nor loose-leaf ads. I don’t read my fortunes at Chinese restaurants. I say yes and no to receipts indeterminately, but when I say yes, I crumple them up and throw them away.

My brother had boxes and three-ring binders for every type of ephemera, a meticulous system I’ve envied since I was eight. But I wanted to be his opposite, an impulse which won out. There was never any method to my bookshelves, for example. Series scattered across tables, nightstands, rooms of the house. Whatever I needed, I’d find. Maybe something would surprise me.

I hated the disarray, honestly, but striving for method felt like mimicry. Like I was trying to be him. But maybe I’d have only been more me.

I thought myself in circles for most of my childhood. I read his diary once. He was fourteen, maybe, so I’d have been eleven. I can’t remember his entries, only my resulting weeks of persistent anxiety. I wasn’t afraid he’d find me out, but that I’d become incapable of distinguishing my thoughts from his. I’d read inside his mind, and he’d been absorbed into mine in return. Every thought I thought, every idea––hadn’t I read it in his diary? I was overwhelmed by helplessness, by this idea I wouldn’t ever become a whole person on my own.

—

The next morning, I’d already received a response. He had attached an image, but I read the text first. He had written, It’s simple, really. I take something in, something I know was meant for me. It becomes a part of me. Everybody’s words, they sit inside me. And then I pull them back out, and then they make sense. He wrote, It’s nice to hear from you, Kris, and added a smiley face after his sign-off.

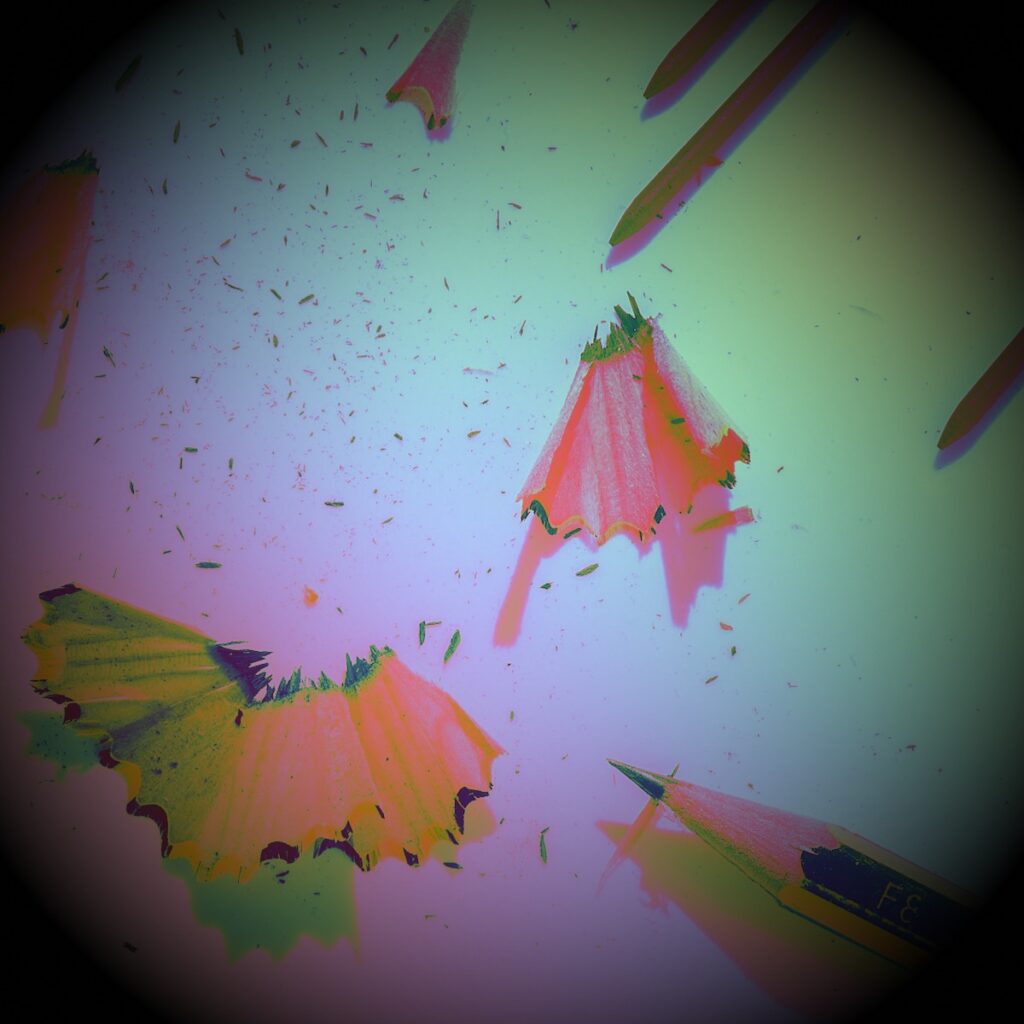

When I opened the image, I saw my email transcribed exactly, in words shaped by dark, feathering ink, surrounded by fragments of others’ messages. Only a glimpse of the wider project, zoomed-in and poor quality.

I was about to close the image when fine lines of pencil caught my eye.

I’ve been thinking about everything. I’m wondering and writing.

I’ve been the headphones, the inputs, her, you.

I make it all. I, me, art.

Between the lines, a message from my brother to me. Or a message from myself to myself. I wasn’t quite sure; I could have missed it.

Regan Mies is currently based in Hamburg, Germany, where she teaches English, writes, and translates with the support of a Fulbright grant. Her work has appeared in the Cleveland Review of Books, Necessary Fiction, the Asymptote blog, No Man’s Land, On the Seawall, and elsewhere.

Image source: Eduardo Casajús Gorostiaga/Unsplash

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.