In Making Progress, writers talk about their work by way of a project they’re in the middle of finishing. Materials include: scratch paper notes and very rough drafts, abandoned opening sentences and weird internet searches.

The point is to get a glimpse into how they put their stories together.

The idea is to say, sure, let’s pull back the curtain.

I first met James in Seattle some years ago, while attending a reading of his at Pilot Books. I remember being struck by the big heart and quiet, often lonesome humor of his prose, Yeh’s superb ear for dialogue and fine eye for life’s everyday wonders. Here he discusses his writing process via an unfinshed story about a young man and his Taiwanese father entitled, “What About the Townhouse?”

Welcome: James Yeh

There’s something special about language that is in some way “off.” I am reminded of the Tobias Wolff story “Bullet in the Brain,” where the main character recalls, in his dying moments, a scrap of unexpectedly musical incorrect grammar: “Short’s the best position they is.” Lydia Davis writes of similar misfires, such as in her story “The Language of the Telephone Company,” the entirety of which consists: “The trouble you reported recently is now working properly.” In these moments something more seems to get said, something beyond language or narrative.

One of my favorite things to do is to write down any bits of “incorrect” language that I happen to overhear. Because I think dialogue is an excellent way of efficiently, and interestingly, communicating a character’s personality—and in their own words—sometimes these overheard bits will emerge in the form of character dialogue in a story.

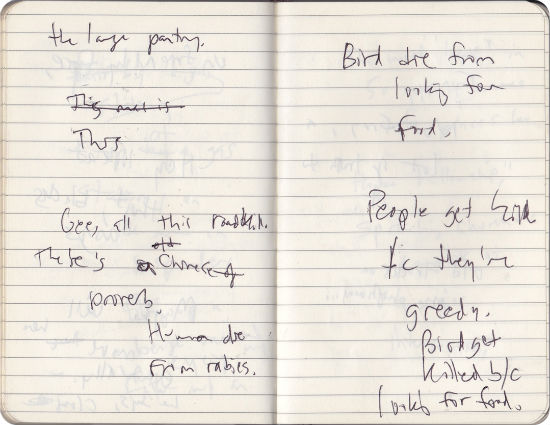

Here are a few lines taken from overheard dialogue that served as the starting points to elements of a story that I am currently finishing, tentatively titled “What about the Townhouse?”, about a young man, his Taiwanese father, a townhouse, and the South:

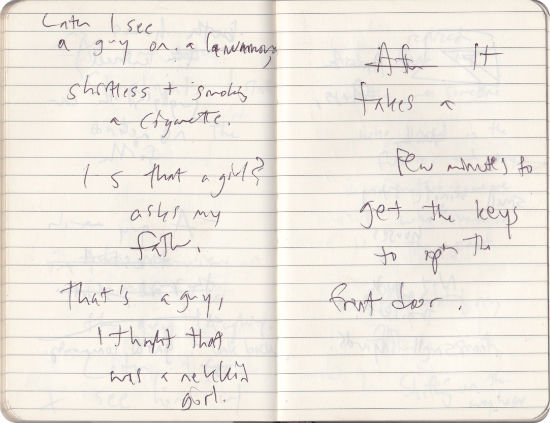

1) I thought that was a nekkid girl.

2) People get killed because they’re greedy. Birds get killed because looking for food.

3) That dumb dog dig hole again?

4) “Use hand to protect the wall.”

5) “Thought become action, action become habit, habit become destination” (instead of “destiny”)

The first example—a remark by my father after witnessing a longhaired shirtless man squatting on a lawnmower, riding down a country road, smoking a cigarette—has since become, in the story, “I thought that was a naked girl, says my father, pronouncing it as ‘nekkid.’ I look over at my father, but cannot tell how serious he’s being.” The moment seems representative of some larger disconnect—the father doesn’t quite comprehend the shirtless man, the son doesn’t quite comprehend the father.

The second and third examples are also from statements by my father. These, too, have made their way into dialogue spoken by the father character in the story—in these particular instances they were incorporated without any change. Taken together the three lines represent, to my view, a colorful, idiosyncratic intersection of the English language, where very different worlds collide into the speech of a single person; in this case, the father in the story.

The last two examples, taken from more recent things I’ve overheard my parents say, aren’t technically a part of the story. But they are, I think, a part of the same world, both in my life and in my fiction, and because of that I’ve been compelled to keep them around anyway, like so many other things I am compelled to keep around. Some of it—most of it—is trash. But you can’t really tell until later, at least I can’t.

My ideas for stories, I’ve found, tend to often come from some type of personal experience, which is to say from something that’s happened to me personally, or that I’ve witnessed firsthand. So, for me—for better or worse—a significant part of my process consists of collecting these “found” materials, such as an archeologist—or a janitor—might do, and then either using those bits as starting points for a character or “refining” these things into a form that might make sense within a particular story. Another way to describe this process could be as a kind of impossible alchemy or perhaps, more accurately, “that thing a toddler does, when they keep trying to jam a triangle-shaped block into a square-shaped hole, then realizes that there are other holes, of different shapes, and tries jamming it into those.” Or, to truly belabor the metaphor, instead of all the jamming, the toddler discovers he’s had a knife in his pocket all along and, realizing this, starts to use it.

James Yeh is a writer, editor, and occasional DJ. His fiction appears in NOON, Fence, Tin House, and PEN America, as well as in several anthologies, and his nonfiction appears in Vice, the Rumpus, and the Faster Times. His chapbook, “9/16/10,” published by Swill Children in 2010, was selected as a notable story in Best American Nonrequired Reading 2011. A recipient of fellowships from the MacDowell Colony and Columbia University, he was a 2011 Center for Fiction NYC Emerging Writers Fellow. Currently he is at work on a novel called “I Love and Understand You and Would Be Perfect to You Now.” He lives in Brooklyn, where he coedits Gigantic.

Matt Thompson is a woodworker who lives in Brooklyn. His fiction, book reviews, and interviews have appeared in Ninth Letter, Unsaid, The Collagist, elimae, and Spork, among others. He is concerned primarily with fiction writing and running long distances.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, Google +, our Tumblr, and sign up for our mailing list.