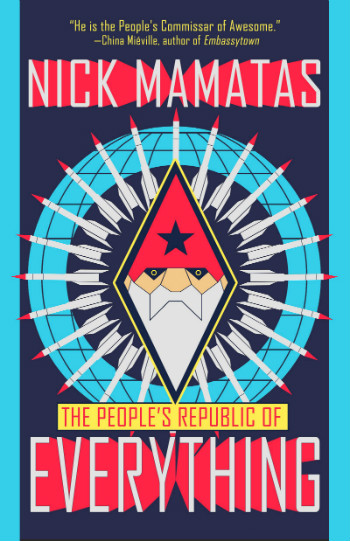

There’s a telling moment to be found in the history of one of the stories in Nick Mamatas’s new collection The People’s Republic of Everything, likely the only collection you’ll encounter this year that includes both a counterfactual account of Trotsky’s early days and an account of a garden gnome-turned-nuclear weapon. It comes after “Slice of Life,” a tale of a particular corner of medical research and the philosophical tangents it inspires among those involved in it.

Mamatas discusses the history of each of the components of the collection–which includes a short novel. For “Slice of Life,” he discusses his plans to retire from writing science fiction in early 2013–a plan which was abandoned after his wife announced that she was pregnant. “Babies cost money,” Mamatas writes. “Crime doesn’t pay. Neither does literature.”

Even so, there’s a tension found in these stories and their relationship to genre that provides an interesting subtext for the collection as a whole. “Slice of Life” is one of the handful of realistic stories in the collection, but even it feints in the direction of the surreal, as it opens with the donation of a particularly singular body to science.

Some of the pleasure of reading Mamatas’s novel I Am Providence comes from the way he navigates the space between crime and horror fiction. It’s centered around a murder at a horror convention, but there’s a question of whether or the supernatural will make an appearance–and that question of whether or not this book about cosmic horror devotees would itself transform into a work of cosmic horror is a surprisingly effective way to create narrative tension.

That unpredictability is used to memorable ends in several of these stories. “The Spook School” and “The Phylactery” both begin in a recognizable and realistic vein, but each one tweaks the bounds of that in their own way–one subtly, one less subtly. “Tom Silex, Spirit-Smasher” contrasts the energy and optimism of pulp heroes with the more mundane lives of those living in the wake of their creators. And “We Never Sleep” riffs on the life of a writer on the fringes and throws in an unsettling eschatological conspiracy.

It doesn’t hurt that, as in “We Never Sleep,” Mamatas frequently ventures into interesting political territory here. “Arbeitskraft” is an alternate history tale of body modification, capitalism gone awry, and the tortured soul of Frederick Engels; “The Great Armored Train” blends an account of the Russian Revolution with a narrative element that defies the worldview underlying many a political movement. It’s a case where the specificity works decidedly well: Mamatas is clearly interested in the ideas beneath the surface, and isn’t simply using them as historical window-dressing.

Specificity also crops up in the use of Long Island settings, from the textual experiments surrounding a surveillance experiment in “North Shore Friday” to the short novel “Under My Roof,” in which a frustrated suburban father creates a nuclear weapon and declares his home to be an independent nation. Here, too, there’s an overwhelming sense of being watched–both from the government’s reaction to this new micronation to the way that narrator Herbert navigates his talent for telepathy.

It’s probably no coincidence that these tales of suburbia also fold in nods in the direction of omnipresent surveillance. Mamatas’s fiction is at its best when its approach to genre is dizzying; the convergence and misdirection on display here make for a memorable foray into their creator’s mind–and into world that might have been.

***

The People’s Republic of Everything

By Nick Mamatas

Tachyon; 318 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.