The other day at the coffee shop, a young woman asked me what I was reading. When I told her it was a new biography of Nelson Algren, she drew a blank. It wasn’t until I mentioned Algren’s long affair with Simone de Beauvoir that her face lit up with recognition. This woman is well-read and has lived in Chicago a few years, but she’d never heard of arguably the city’s greatest chronicler. And she’s not alone. Though Algren won the very first National Book Award in 1950, and was considered a top tier writer for a decade or so thereafter, he’s rarely mentioned in the same breath as Hemingway or Faulkner anymore. I’m hoping that Colin Asher’s definitive portrait of the man might change that.

Algren’s great run of books, starting with the 1942 publication of his second novel, Never Come Morning, the short story collection The Neon Wilderness (1947), The Man With The Golden Arm (1949), culminating with A Walk On The Wild Side (1956), stands up against most any writer in American letters. What happened to the man and his work thereafter has been the subject of fable and rumor until now. Algren himself is partially at fault for being a shameless self-mythologizer, especially later in life.

There are two previous biographies of Algren, which, while both having their good points, often took his stories about himself for fact and never satisfactorily explained his fall from grace. By a combination of meticulous research and a smooth prose style, Asher has fashioned a narrative that is both a joy to read and is utterly convincing. I’ve been heavily invested in Algren’s work for over thirty years, but learned many new things from this book.

Asher’s overarching thesis is that, contrary to the heretofore accepted idea that Algren lost his inspiration due to writer’s block and alcoholism, he was in fact inordinately affected by FBI surveillance for his leftist sympathies. Access to unredacted FBI files—unavailable to previous biographers—makes for compelling evidence that Algren lost many professional opportunities due to their surveillance. His spirit was likely broken by this sustained harassment. The file was open for nearly thirty years and cited colleagues and acquaintances as regular informants. So, what has previously been taken as Algren’s paranoia, is now borne out as evidence in black-and-white. That is not to say, of course, that Algren didn’t do his part in torpedoing his own career.

Coming out of the Great Depression, Algren was of the generation which truly believed a socialist revolution was coming. He glorified the Soviet Union and even defended Stalin’s horrific show trials. But when the political winds in the country shifted, unlike so many in his circle, he neither named names, went underground, nor shifted to the right. He continued to champion those on the bottom of the societal heap and paid a steep price for it.

One of the most valuable contributions Asher has made is to flesh out the supporting characters in Algren’s life. While his famous affair with Beauvoir has gotten plenty of ink, his relationship with his wife, Amanda, who he married twice, was never more than a footnote until now. Through three-dimensional portraits of the people and places key to the man’s life, Asher has fashioned as full a picture of Algren as any of his long-suffering fans could hope for.

He also doesn’t mince words when analyzing the scattershot work Algren produced in the last twenty-five years of his life. Tired of being harassed and broken by personal and professional reversals, Algren cynically began writing for money rather than as a quest for truth. There are glimmers of inspiration and insight, but he was never able to sustain a long narrative again without lapsing into mean-spirited score-settling or cringe-worthy jokiness. Much of his late work is painful to read and Asher acknowledges it. And yet, despite this, the man became an inspiration to a who’s who of American literature.

Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, Bruce Jay Friedman, and Kurt Vonnegut are but a few of the great up-and-coming writers who crossed paths with Algren and were encouraged to keep at it. Anyone who reads Asher’s book will be convinced that Nelson Algren deserves a place in the canon (if such a thing still exists in today’s ever-shifting climate.) His tireless championing of those who got the short end of the stick reads more relevant in our current polarized society than it ever did before.

***

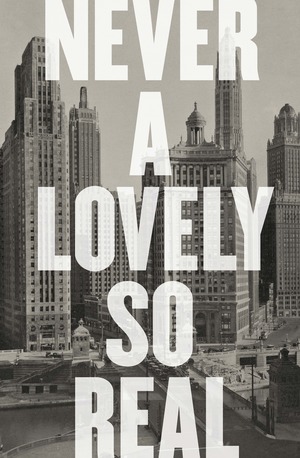

Never a Lovely So Real: The Life and Work of Nelson Algren

by Colin Asher

W.W. Norton; 560 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.