A lot of writers were in bands when they were young, but what about making music after you’ve published a few novels and are old enough for the romance of late night shows in dive bars to have dimmed? Is it something most people outgrow for a reason? A compulsion related to arrested development or midlife crisis? Or is performance intimately related to the act of writing in ways that are slow to reveal themselves?

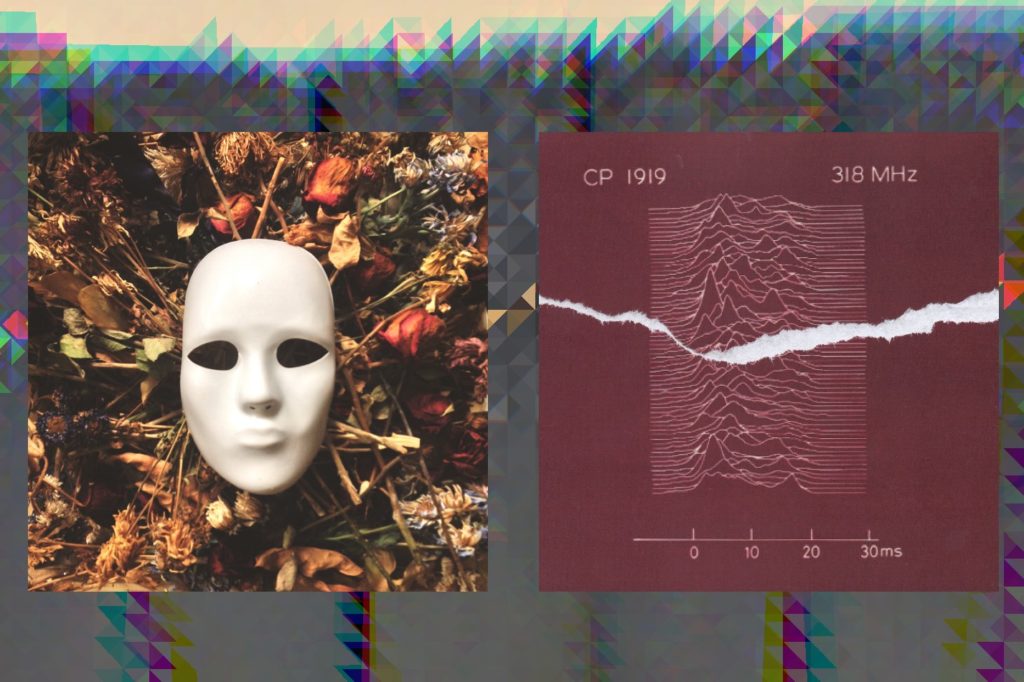

There aren’t many serious fiction writers who are in active bands, so I was excited to talk with Meghan Lamb, author of the novels Failure to Thrive and COWARD, and lead singer of Chicago’s Kill Scenes, which recently released their stunning album Masque. I’ve also published two novels and my band Julian Calendar put out new music this fall—the EPs Forgeries of the Future and Severed Tongues Speak. We quickly found that we had a lot to discuss.

Over the course of several weeks, we talked about our different paths into music, the overlap between fiction writing and music making, the ways performance destabilizes identity, the role of sexuality in vocals, and the strange, unsettling, and exciting ways that words activate bodies. [Intro by Jeff Jackson]

Meghan Lamb: To begin, I’d like to talk a bit about our various twisty-wisty paths to “beginning” in our respective bands, and to our “beginnings” as writer-musicians/musician-writers.

For me, even before I was in Kill Scenes, writing, performance art, and music-making were all overlapping–and sometimes incestuous–pursuits. I did my undergrad studies in literature/media at Indiana University in Bloomington, which has a really vibrant independent music scene. Jagjaguwar, Secretly Canadian, and Bluesanct are among the numerous amazing indie labels based there, and–at least when I lived there–there was a thriving culture around house shows and basement shows (and a lot of punk bands and odd noise projects that were basically the result of friends hanging out and having a conversation in the spirit of, “Hey, wanna make a band?”; “Sure, why not, let’s make one right now!”). “Becoming a musician” thus felt like a totally accessible process, and “performing live” felt equally tangible and attainable (because there was always a DIY basement show willing to throw you in the mix with a bunch of other random acts). And because of that, I also began with a certain measure of experimentation and openness about what constituted “music”/what it meant to be a musician. I remember a particular noise artist–I think his name was Willard?–whose entire project seemed to be based around exploring the weirdness of his intensely skinny 7 foot-tall body and using it to surprise and scare people. The first show I went to where Willard made an appearance involved him opening a door at the top of the staircase (the stairs spilled right into the living room where everyone was gathered for the show), tearing ass down the stairs (naked and covered in fake blood), and basically just wailing and writhing for 7 minutes. My reaction was: “Oh FUCK! I want to make things like THIS!”

Jeff Jackson: I love stories like that about the transformative power of punk scenes and the DIY ethos to help people realize that making art, music, film, whatever is something they can do. It’s something I experienced myself in various ways. It’s a powerful story and it never grows old for me. I think it’s something every creative person needs to hear because it’s a reminder of how often the stories we tell ourselves – about our lives, our talents, our bodies, our limitations — are false.

ML: Absolutely! In my early 20s, I made a lot of strange outsider art (for lack of a better thing to call it) that combined music, writing, performance, and…weird body stuff…under the name Iron Like Nylon. The Iron Like Nylon project actually started out as kind of a “literary covers” project in the sense that all of my lyrics were derived from literature: Emily Bronte-inspired songs that included quotes by and about her, performative personas taken from “mad woman” archetypes in Elaine Showalter’s The Female Malady, and an entire album–In the Absence of Love–that was derived from George Bataille’s beautiful/awful/hilariously stupid poetry. I couldn’t really play any instruments very well, so my “instruments” were an odd melange of thrift store toys, “found” noise (sound effects downloaded from YouTube), and “white noise” (literally echoed layers of the “metronome” in Garageband). 90% of the music was my voice, though, because that was far and away the strongest and most interesting raw material I had to work with. I have a number of family members who were involved in opera, so I actually took voice lessons on and off throughout my childhood (and basically learned how to do the things I wanted to do from those lessons/ignored all the rest).

I made weird little albums to sell at shows, but when I’d perform at the shows themselves, I’d usually do something more akin to performance art because my actual “music” was unperformable (or, at least, I never came up with a good way to perform all those layers in a live setting, and I didn’t have money for a lot of equipment anyway). A typical “show” might involve a reading from Wisconsin Death Trip (wearing a giant deer antler headdress made of wire and duct tape), a drone track made from slow-building layers of white noise, a 15 minute-long cover of “Eternal Flame” comprised of about 6 minutes of screaming, and a pantomimed suicide with lipstick.

I was always trying–and failing–to be in a “real” band, but the bands kept breaking up over silly dramas and artistic tiffs and never really assimilated into anything. So, years later, when one of my old Bloomington friends–Sean Whittaker–asked if I wanted to make music with him, I enthusiastically agreed. I knew that in addition to being a talented multi-instrumentalist and songwriter, he was a great sound engineer (that’s actually what his older brother does professionally), and that he’d be able to put so many ideas into action that I didn’t have the language or technical understanding to pull off.

The band has evolved a lot over the years (including ten years without me even being in it because I moved out of Chicago). This most recent album is really special to me because it’s the second one featuring me as the lead singer (after a decade-long gap since that first album Sean and I recorded).

JJ: Even though I’ve been a music obsessive my entire life and worked as a music critic, I came to making music fairly recently. My friend Jeremy Fisher asked me and poet Amy Bagwell if we would write lyrics for his music. Amy was able to craft some wonderful words that perfectly fit several of his songs. But that was beyond me.

What I could do was write a set of lyrics then improvise a melody over riffs that Jeremy had written. Together, we were able to shape this material into songs. The initial idea was Jeremy would sing, so I was really playful in my approach to writing. One of my private prompts was: “What would it be funny to hear Jeremy sing?” That’s how the lyrics to our seductive slow-jam “Numb” (on our EP Crimson Static #3) originated.

Since I’d been singing the songs as we wrote them, Jeremy thought I should be the lead singer. I accepted, even though I was terrified. We added Scott Thompson to the project because he’s brilliant at playing any number of instruments. Amy didn’t want to perform and I wanted a female voice in the mix, so Hannah Hundley joined as co-lead vocalist. Like me, she’s not a trained musician but she draws on an enormous knowledge of music, film, and literature.

I don’t think I would’ve been able to do this when I was younger. I would’ve been far too self conscious. Too worried about making a fool of myself. One of the nice things about getting older is that fragile sense of pride has evaporated. Now I just don’t give a fuck.

ML: It’s funny because “not giving a fuck” is usually associated with being young and inexperienced…trying new things because you have nothing to lose. But being an older person in a band–particularly, an older person who has dabbled in a lot of different creative projects–can be like its own kind of reverse youth. I don’t know if I’d say I don’t give a fuck now, but I definitely give fewer fucks.

JJ: I know many writers who were in bands when they were young, but most of them shed that part of their creative output as they got older and more established in their writing life. Why do you think so few “established” writers are still involved in music? Or maybe the better question is why have you not only stayed with it but deepened your commitment to music?

ML: Well, the obvious answer to the first part of that question is “time.” When you’re young, you’re trying out different creative outlets and seeing what “sticks,” perhaps what’s the “best place” to put certain thoughts and drives into. And as we get older (I’m 37, so I’ll let readers establish my oldness currency for themselves), I think there’s a lot of pressure to pick one of those outlets and make more of a “career” out of it…or, at least, to make that the outlet that’s primarily associated with ourselves.

For a long time, I felt like I had to choose between music and writing…and I “chose” writing from the standpoint of, “well, I feel like I already have a stronger network of connections in this creative field, and the next steps toward making it more of a long term calling are a little clearer to me.” I got an MFA. I published books. I read them at readings. I taught writing. People had already started to see me as a writer, whereas fewer people knew about the band.

But as I published books and continued to build up my identity as a writer, I felt a certain anxiety within latency periods when I was wondering what to make my next book “about”…which ideas to commit to, how to get my brain back into writing. And that’s part of what brought me back to the band. I wanted to do things with my body. I wanted to channel the kind of energy I wanted readers to feel from my books into my body. And I think part of what’s deepened my commitment is the feeling that written language and body language aren’t mutually exclusive in the least. They nourish–and feed off–one another in really interesting ways.

JJ: Julian Calendar is the first real band I’ve been in and I’ve approached it almost like a theater project, which is my other artistic background. What you said about feeling the emotion of the material in your body really resonates with me.

Unlike you, I’m not a trained or naturally gifted singer, but through my theater training I do know how to be expressive and get the most of a text. I’m used to being on the side of the stage that’s about shaping the text and performance. So for Julian Calendar, I try to look at my strengths and weaknesses as objectively as possible and work within those. To remove ego from the equation and direct myself toward the best performance. To listen to my body more closely and respond to what it’s doing, to push when possible and also respect its limitations.

Are there things you’ve experienced in the “body language” that have surprised you? The new Kill Scenes album Masque is very much about personas. What about the personas is communicated through body language/sound vs. the words themselves?

ML: I’ve been surprised by how natural it seems to embody different aspects of my own identity through this album…aspects that I haven’t tapped into in awhile, or aspects I’ve always kept kind of shadowy until recently. By “shadowy,” in part I mean…I’m kind of emerging from the closet (as bisexual and also…as sexually weird) with this last book I published (COWARD), and perhaps it feels natural to “emerge” in similarly charged ways with the ways I embody these songs. There’s language of transformation, emergence, unveiling, performing a new role in almost every song on that album–hell, you can get that even from the titles: “Masque”, “The Chrysalis”, “The Final Act”–and perhaps I’m using performance as a means of exploring the implicit but not always visible/surface level sexual charge of this transformation, emergence, and unveiling in the lyrics.

I kind of think of our vocal layering as bisexual, in a way…haha, or, maybe more to the point, like two different personas having sex within the same person. Almost every track on the album features a certain interplay between my higher (usually/but not always “sweeter”) register and my lower (usually/but not always “more sinister) register. When we’re recording, there’s almost a kind of battle involved to see which “voice” gets control of the song. Sometimes I have very strong opinions that it should be the lower voice or the higher voice, and sometimes those opinions conflict with Sean’s original expectations. Sometimes, I just give him complete control and let him surprise me. Sometimes Sean’s own voice ends up in the songs and surprises me! Sometimes a pitch-shifted caterpillar from an Alice in Wonderland record ends up in the songs and ends up surprising me!

JJ: I like that. Some people have commented that the vocals by Hannah and me sound like they’re dramatizing a single mind testing out different ideas, possibilities, and desires. Or arguing with itself about these things. I think you can hear that on the new EPs, especially the songs “Strt Frm Scrtch,” “King Blank,” and “Language Lessons.” We’ve also been told the two of us together make one good singer. Which is probably right!

ML: I also think it’s interesting to put more surprisingly sinister lyrics into the mouth of that “sweet” high voice. On our fourth album, for example, I gave the song “Word of Warmth”–which features music and vocals that are almost saccharine-sweet, like a Strawberry Switchblade song–the sickest lyrics, like, “The word of warmth/is a suckle of blood/from a severed hand.” It would feel like major overkill to put a lyric like that in a song where the music was already kind of dark and abrasive, and I like the sneaky subterfuge of it…you only notice it if you’re already attuned to the incipient darkness of things that are saccharine-sweet.

I feel like surprising sublayers of these songs have also emerged in the course of performing them live. Actually seeing an entire video of a show–via a recently recorded livestream–was a big surprise to me, not only because I could actually “see” what my body felt compelled to do at different points, but because there was a live chat in the sidebar (that was actually “recorded” in addition to the performance), and I could see which moments people were responding to in ways I didn’t quite anticipate. The song “Whispers,” for example (which I had thought of previously as more of a delicate/pretty song) really seemed to beckon to people in a surprising way. People were putting up a lot of little “fire” emojis at the most delicate (almost whispered) moments of the song. I almost wonder if my overt/loud/slide-y/grind-y sexually performative gestures perk people’s ears and help attune them to quieter moments with a different kind of charge (and allow those moments to resonate). Maybe sex appeal is just a way of beckoning people in and encouraging them to pay close attention (and–of the same merit–a kind of open window for you to do anything you want once you have people’s attention).

There was also a really funny moment in that livestream when I got a sudden impulse to sing a part totally differently than I usually did–at the end of “Skull Wall, where I usually kinda descend down the scale, I made a spur of the moment decision to leap an octave in a moment of witchy freak operatics–and Sean looked over at me with big surprised eyes and a wide open mouth like, “Whoa, damn! Oh, yeah, the song…” Surprising my own bandmates is kind of the ultimate thrill for me, ala, “Oh, you thought you already knew everything that was going to happen in this song, but you DIDN’T!”.

But, back to sex appeal. The idea of sex appeal–or, using sex as an appeal, and perhaps as a means of appealing to listeners in surprising ways–has come up at different points in all of our conversations (usually with the result of Sean “blushing” and me taking the reins of that subject). Julian Calendar does a lot of interesting stuff in terms of “putting charged lyrics into surprising mouths” and using different performers/bodies to complicate listeners’ ideas of what those lyrics “mean.”

JJ: I’m always thinking about how the words can charge the song and the performance. Part of that equation is that Hannah and I both present as mild-mannered people, though we’re both interested in transgressive art.

ML: Sean and I present the same way! Lots of polite Midwestern niceties between gritted teeth, haha.

JJ: Having us sing unexpected lyrics about sex, violence, politics, etc. is a way to startle people out of their assumptions about who we are and what this music is about. It hopes this charges the atmosphere in performance and while you’re listening.

The vast majority of the lyrics are written without a clear idea of who will sing what line. That gets figured out when we put the song together with the band. Hannah and I try out various combinations to see what works. We privilege what sounds exciting over strict meaning. But there are instances when it makes more sense for one of us to sing certain lines.

In “Maraca” on Crimson Static #3 it’s less problematic (but still provocative) for me to be the one shouting “Hit me, hit me, hit me – hit me harder!” In “Belly of the City” (Crimson Static #2), I think it’s more interesting for Hannah to sing predatory lines like “take off your clothes and you can stay / it’s your body I won’t betray.”

For Kill Scenes, Sean is writing many of the lyrics. What is it like to embody those words? Do the meanings change for you through your interpretation of them? Do you feel like there’s a certain inherent sex appeal in them that you’re transmitting – or creating – for the audience?

ML: I wonder if part of Sean’s ethos behind putting words into my mouth/body is…exploring different aspects of his own identity in sneaky ways. Maybe part of the reason he “blushes” is that he doesn’t quite have the language to articulate those questions and curiosities (and that’s why he uses music)! For example: I know that part of the inspiration behind “Acid Black Window” came from a conversation he had with a friend who’s trans about feeling disassociated from your body…or feeling like your whole understanding of what a body is is…morphing and contorting into something strange (changing your basic assumptions about who–and what–you are). Those lyrics are coming from Sean, but there was a lot of creative commingling–body and brain commingling–going in in them even before they were essentially (re)possessed and retranslated by my body.

Maybe part of the reason he “blushes” is also: there’s a certain (unspeakable!) sexual charge to every collaborative creative act. You’re commingling with others’ brains and bodies in order to make the thing happen. You’re fucking with lyrics and instruments.

For me, though, it’s exciting to embody someone else’s words in ways they hadn’t necessarily considered. Like, for example, I usually find myself pushing back when Sean thinks of a particular song–or section of a song–in terms of a higher/prettier register; I’ll feel compelled to sing it lower/more menacingly. Or vice versa. And there’s a certain thrill to covering songs like “Zero” or “Eyes Without A Face” that were written/sung by other dudes and queering those songs just by nature of putting them into me.

We talked a bit about this in terms of “Dekadenz,” the last song on Julian Calender’s new Severed Tongues Speak EP….the choice to put certain lyrics into your mouth versus Hannah’s mouth, the ways you even experimented with having your drummer sing them, and the ways the different voices changed (and queered) the pitch of the song. I’d love to hear a bit more about that!

JJ: I love your version of “Zero” for that reason. I’m definitely attracted to queering cover songs and changing their meaning by who sings them and how they’re sung. We recorded a version of the Willie Dixon/Doors song “Back Door Man” where Hannah sings lead. Jeremy transmuted the blues machismo swagger of the riff into lovely minor chord filigree, so it’s closer to a Cocteau Twins number. And it’s wonderful to hear Hannah sing “I’m a back door man. The men don’t know, but the little girls… understand.”

ML: That’s such a wonderfully layered cover, by the way. Initially, there’s the comedy/hilarity of Hannah’s delicate voice singing those lyrics, but once the listener gets over the dissonance, those lyrics seem “right” in her voice: beautiful and oddly touching.

JJ: For “Dekadenz,” I wrote the lyrics without any idea who would sing them. I would’ve been happy if Hannah had sung the entire song, but it worked out best when she sang the chorus and gave it a wonderfully disaffected feel. We tried the verses different ways and discovered they needed to feel a bit sleazy. So I did my best lounge lizard turn, trying to sound seedy and louche. Hannah added some crucial background touches. She described the lyrics as filthy like a pre-code Ernst Lubitch film: a perversion that’s put across so subtly it dares you to notice it.

A few lyrics are written with the idea of Hannah or me singing lead. Sometimes that initial impulse sticks, like the song “Profondo Rosso” (on Crimson Static #2) which was written for Hannah and inspired by her love of Dario Argento movies. Occasionally, the song has other ideas. I thought either Hannah or our drummer Bo might sing lead on “The Drowned Boy,” a song that will be on the next EP. But it turned out to work best when I sang it. It’s a song about illicit desire that became queer because a man voiced the lyrics. In this particular case I don’t think that’s more or less interesting, but it is a significant shift.

I don’t know about you, but often I find myself simply grateful when a song “works.” Whatever it takes to get there, I’m increasingly willing to do. Rewriting lyrics, tossing out sections, letting the meaning change. Even more than in writing fiction, creating songs feels like a delicate process to me. A form of magic, almost. Does the music-making process feel different to you than writing? Do you have similar ambitions for the words in songs vs. fiction?

ML: Music is definitely different in the sense that–as I think you’re implying with the process of “whatever it takes to get there”–I have a lot less control over how the band works together and how the audience interacts with a song than I do over how the audience interacts with a book (wherein I’ve worked on it alone, of my own accord, fretting over every sentence).

Well, actually…now that I’m really inhabiting this question, that doesn’t feel true at all. I ultimately never have any control over my books either! But perhaps working with more of a collective forces me to let go of control before the art reaches an audience. With a book, there’s an almost ritualistic process of creating the thing and “letting go.” With music-making, the whole process–from the very beginning–is a kind of letting go, of experimenting with different things until the song “works.” Not that I don’t constantly experiment within my writing, but I think a lot of that process is invisible even to me (or, at least, starts to feel invisible the moment I decide: “The book is done! The book is now a book-object!” and the finished thing becomes what I associate with that particular creative effort). With music, even when you finish an album, you perform it very differently (or, at least, I do…I always try to do things live that wouldn’t have made sense on the album, like kneeling down and screaming a part that was softly whispered on the album). And my band performs a melange of other songs from different albums in conjunction with one another, so they’re radically recontextualized. To some degree, you’re going through the creative process again and again and again, not only when you’re creating a song or performing live, but every time you practice as a group. Nothing is ever a fully “finished” object.

I suppose, in that sense, the idea of “ambition” also means something totally different to me when it’s applied to music. Or…perhaps there’s an inherent tension between “ambition” (which is often associated with personal, autonomous drives) and the “music-making process” (wherein each member’s “ambitions” collide and fuck with one another).

But I think…maybe part of what you’re (also) getting at is the question of: are your “goals” different with song lyrics versus books. For me, they are, but they also aren’t. I was tempted to say: “With music, there’s a certain impulse to entertain–to give the audience a show–that I don’t have in writing, which is much more controlled, and much more about articulating my own obsessions.” But that’s an oversimplification. I’m definitely articulating my obsessions in music–the dark power of delicate things, the fragility and vulnerability coursing through big powerful things–but I’m also performing Sean’s obsessions–his attempts to make peace with visions and dreams (in both a figurative and literal sense; he has sleep paralysis and extremely vivid nightmares, so the strange specters of songs he writes come from a kind of lived experienced). And, likewise, I’m definitely entertaining to some extent in my writing: not in the sense that I’m pandering or catering to anything I think the reader “expects,” but in the sense that I’m constantly searching for ways to make things palpable through language, to engage the reader by embodying experiences in a way that makes them feel (something they didn’t expect to feel?).

With musical performance, at least, I think there’s almost a confrontational quality to any ambition you might have from the standpoint of…the audience is looking at you, delivering the thing. I really like that. I kind of get off on that. I almost feel like I’m preying on the audience, in a sense. I keep talking about how music is all about letting go of control, but conversely, in that 45 minutes or however long your set is, you captivate them…and, in that sense, you do control the whole viewing and listening experience (whereas who knows what the fuck readers are doing with your book, beyond your view, behind closed doors, haha).

Wow, I just realized that I did a full 180 in my response to your question, but that seems totally appropriate. No take backsies.

JJ: Maybe this sense of “performance” is something that links music and literature. I know we’ve both been inspired by writers like Kathy Acker and Sarah Kane who used the page as a performative space in various ways.

ML: I’m really curious about the control–or lack of control–you feel when you’re performing live, especially since you come from a different kind of performance background where–as you mentioned–you were usually on the other side of the stage, directing or otherwise sculpting what the audience witnessed. Do you feel like you have a stronger appreciation for the interplay between “both sides,” now that you’re the one getting on stage and performing?

JJ: I’ve always had a great respect and admiration for actors and theatrical performers. I trained some as an actor in college, but I just wasn’t very good. That sort of performance – where I had to remember lines, stage directions, character motivations, the director’s suggestions, and be responsive to the other performers – was frankly exhausting. All those limitations constricted me to the point that I had almost nothing to offer.

I’ve been surprised to find that performing with the band is far more energizing. Maybe it feels safer than theater performance because I’ve written the lyrics myself and helped to shape the music. It’s something that’s been part of my body from the first flickering impulse – I’m not having to try and embody someone else’s artistic ideas. I also feel like I have more latitude to try different things with the songs and the performance itself. It feels more open and expansive. In theater, my meager talents kept hitting a very physical ceiling – namely, the audience.

The first time Julian Calendar played live it was nerve-wracking, but something about being on stage in that way made instinctive sense. I was far from great, but I could sense the possibilities for what could happen. The potential for both losing myself in the moment and holding an audience’s attention. I don’t know whether I’ll ever get to those places, but it was the first time I had performed and had the taste of blood in my mouth.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.