Edward Gibbon is best-known for his The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a work so mammoth that its abridged edition is still a sizable doorstopper, abounding with information about the Roman Empire’s culture, systems of government, and rulers–both good and bad. And if that was all that Gibbon had featured, that would suffice to confirm its classic status. But there’s plenty more to consider in Gibbon’s book, both structurally and in terms of the vast influence it’s had on the centuries of work that followed.

There’s a clear point of view in this massive history, colored both by Gibbon’s own beliefs and by a sense of historical inevitability. We know how this story ends, after all: the Roman Empire, first divided, and then overrun. Nations, Gibbon tells the reader, are bound to eventually fall, either as the result of outside pressures or internal flaws. It’s a cautionary tale, and it’s difficult to read it without extrapolating Gibbon’s narrative approach to different times and places throughout history. There are also explorations of the early days of both Christianity and Islam, and examinations of how each faith took root and established itself as a major factor in the everyday lives of countless people, and a significant part of the political landscape.

For all that Gibbon’s Decline and Fall has had a substantial effect on history, it’s also worth exploring its effect on fiction. The historical sweep and basic structure of Gibbons’s book, which moves from the large scale to an intimate level, and back again, can be seen as echoed in a small but memorable coterie of novels. Angélica Gorodischer’s surreal Kalpa Imperial, Jan Morris’s inventive travelogue Hav, and Jeff VanderMeer’s phantasmagorical City of Saints and Madmen all have more than a little of Gibbons’s literary DNA in them. All contain a sense of past splendor (and past brutality) that continues to hold sway over the present; all, too, contain a sense of something lost to the ravages of time that will never be regained.

Jean d’Ormesson’s 1971 novel The Glory of the Empire is subtitled “A Novel, A History.” With a new edition out in the United States next week, it’s worth considering it, too, as a fictionalized heir of Gibbon’s sprawling work of history. It’s a comparison that d’Ormesson embraces throughout. Although written in an era where the author could discuss matters of sex and sexuality more frankly than Gibbon, the scope of the two books is quite similar, covering the permutations of a vast empire than evolved over time, eventually transforming into a diminished version of its past self.

It isn’t hard to read The Glory of the Empire as a distinct homage to Gibbon. For starters, Gibbon makes an appearance. D’Ormesson has structured his fictional history with all of the trappings of the real thing, including extensive end notes, which often cite fictional works that reference the Empire, an imagined rival to Rome (although not necessarily the Rome that we’re familiar with). In literally the first of these notes, d’Ormesson writes, “Gibbon’s Rise of the Empire remains the best study of the Empire’s origins.” It’s a wink, but it’s also a knowing one: in the alternate history described by d’Ormesson, of course Gibbon would have been fascinated by the Empire. And in the Bibliography that closes the narrative, there’s a sly poke at the vastness of Gibbon’s history: “A 27-volume History of the Empire by the author of the present work is in preparation.”

Structurally, d’Ormesson’s book also incorporates some knowing nods to Gibbon. Rome is established as the Empire’s rival, headed by “the high priest, at the same time ruler and prince, who bore the illustrious title of archpatriarch.” Occasionally d’Ormesson uses actual historical figures as points of comparison, which includes the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, who also has a significant presence in Gibbon’s history. There are also echoes of Gibbon’s Rome in d’Ormesson’s Empire: a cavalcade of rulers of varying skill levels, the presence of barbarians on the outskirts, and a sense of heights and glories that will never be recaptured.

One of the interesting ways in which d’Ormesson diverges from Gibbon’s template is in showing the ways in which the Empire influenced subsequent culture. There are references to everyone from Michel Foucault to Walt Whitman, Andre Gide to Raymond Queneau. (That the co-founder of the literary organization Oulipo is cited here seems very significant.) And that, perhaps, marks the chief way in which d’Ormesson’s fictional history and Gibbon’s very real one are distinct. For d’Ormesson, this fictional empire’s influence on culture is an aspect of the plot to be manipulated and used judiciously. For Gibbon, his work has entered that realm of cultural influence, which has in turn made itself felt in histories real and imagined–and likely will for generations to come.

This essay first appeared at Signature Reads.

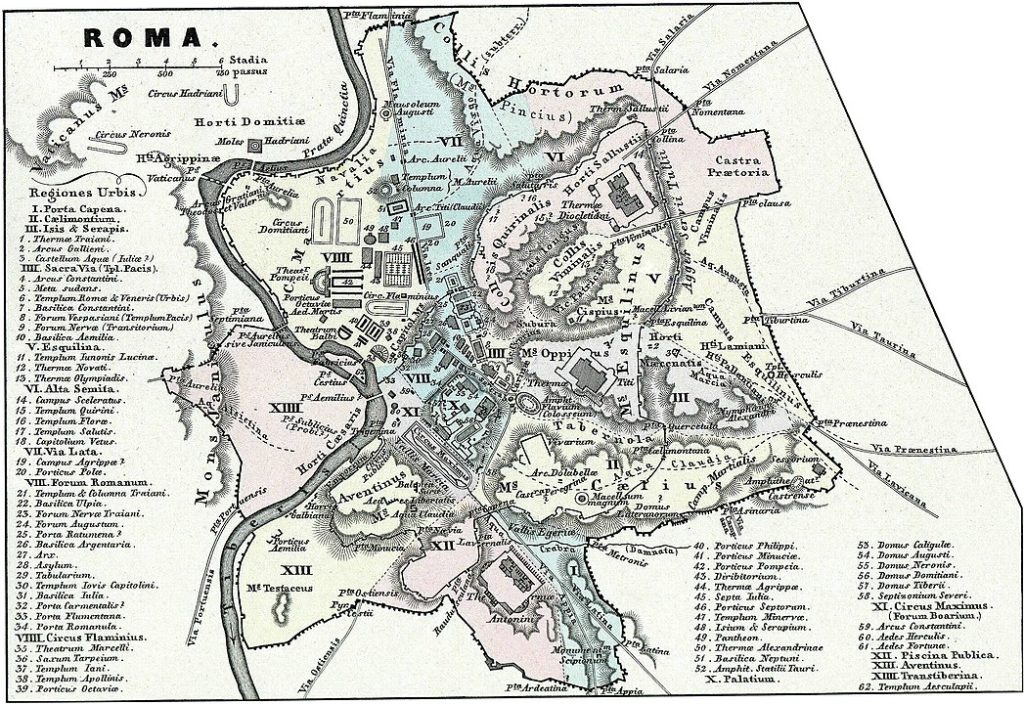

Image: Theodor Menke – ATLAS ANTIQUUS Karoli Spruneri opus tertio edidit Theodorus Menke. Nr. XX, Public Domain

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.