“I felt … drawn to the desert where fire blossomed in silence,

sprouting from a great, featureless plain that

could have been the end of the world or the beginning.”

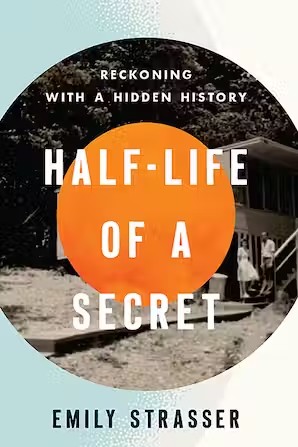

Emily Strasser’s Half-Life of a Secret is ostensibly about unraveling the mystery of her grandfather George, who was a scientist at Oak Ridge. In George’s time, Oak Ridge was a secret city, lesser-known than its sister Los Alamos, but built to do the same work—the construction of nuclear arms. George is, in turn, a man of secrets, one who was an intelligent, high-ranking official but also suffered from mental illness. Strasser attempts to uncover his history in order to better understand him as the patriarch of her family as well as a person who participated in the construction of the bomb that killed upwards of 135,000 people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“This story is and isn’t personal”

As the author attempts to track down people who knew her grandfather, her journey is immediately complicated by the fact that the work people did at Oak Ridge was secret, even from themselves. The idea of a ‘greater good’ (i.e. the war ending) was leveraged against people to feed a war machine. Strasser writes that “[a]biding by the rules without understanding the purpose or consequence proved to be the most efficient strategy” for the government to employ at these secret cities. For example, young women were hired to operate a calutron, which “enrich[ed] the uranium that would wind up in the Hiroshima bomb, but … didn’t know that.” Oak Ridge, Tennessee was like a sleepaway camp for adults, they were isolated from people they knew and given slogans to build a ‘team mentality’, all while only a few actually “kn[e]w what they have been producing.”

While this side is fully represented, Strasser approaches her understanding from an intersectional perspective. She explores the consequences of racism and colonialism that led to the creation of the atomic bomb. From bigotry in this ‘utopia’ still very much a part of American culture during this time to understanding how Dutch colonization led to uranium mining in Africa, this book does an excellent job of contextualizing this time period and pulling apart all of the threads that led to the exact moment the “Little Boy” bomb left the Enola Gay. The largely unknown stories included that of Ebb Cade, a Black worker at Oak Ridge who was involved in a car accident. At the hospital inside this ‘safe’ community, it was decided to use him as a human guinea pig and they shot him up with plutonium to study its effects. This stark example would shock many Americans who know about Nazi testing on human subjects but would never imagine that happening in the heartland. There are other more blatant examples of racism in Oak Ridge and they stand to remind us that “[w]hile the propaganda signs in Oak Ridge prompted residents to imagine the sufferings of soldiers on faraway battlefields, compartmentalization taught them not to extend such empathy to their neighbors” and it becomes easier to understand how people are able to dehumanize others, even to the point where they eradicate entire cities.

“Our stratosphere is still stitched in radioactive particles.”

The heart of this book, of understanding George, lies in Strasser’s exploration of moral obligation in relation to the bomb. The reader sees the psychiatric effects of the Hiroshima bombing on Oak Ridge employees, including her grandfather, and their horror in understanding how they contributed to this destruction as well as the unknown possibilities in the future. Still, there is a tension between the difference in her perception versus those who lived through it at Oak Ridge. In her research, one person hurls an “accusation of poetry” at her, meaning that her understanding has been altered by a romanticizing or distorted perception of war. Strasser is not without her own judgments on the situation and while she gives the Oak Ridge inhabitants space in this study, she outrightly states:

“I have been told to contextualize the horror of Hiroshima in relation to the Rape of Nanjing, the bombing of Dresden, and any number of other historical atrocities, as if the existence of other atrocities mitigates the severity of this one.”

George was a scientist, it was his contribution to the war, and Strasser has a skill in breaking down the science in a way that’s easy to understand. Her talent is in combining science, history, sociology, and humor—the science never stands outside of its place in time and the people before and after. The amount of research is outstanding; this is a collage of historical documents, news reports, poetry, and abundant first-hand accounts from people at Oak Ridge as well as Hiroshima. The penultimate chapter, sees Strasser visiting the Japanese city seventy years after the bombing. She visits with hibakusha, survivors who are willing to tell their stories. Their testimony shows how close history is, that history is living. This structuring highlights the generational impact of the bombing: on the residents of Hiroshima, of Oak Ridge, of the world at that time, and the world now through all of their descendants. This novel embraces the complexity of this issue. At one point, one hibakusha named Nishida Goro tells Strasser “What is bad is war. Not American people, not American government, but war itself.” The reader is never given one opinion about the bomb without seeing the refraction of its opposites and tangents.

Utilizing a wealth of detail and research, Strasser has created more than a vulnerable and touching biography of the complicated man that was her grandfather. Half-life of a Secret is a deftly-rendered sociological exploration of science and the mind, and how the combination of those two elements can have profound sociological and humanistic impacts. Many scientists I’ve met espouse an ‘amorality’, in that they think they only deal in hard facts and that their work lives outside social mores or systems of belief. With a talent equal to Maria Popova, Strasser illustrates that science is inextricable from its social impact. This book is a combination of Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, Olivia Wilde’s Don’t Worry Darling, and Steven Okazaki’s White Light/Black Rain. The marvel in these pages is how it captures the prism left behind by a seminal event and the beautiful and, yes, poetic rendering of intergenerational trauma.

“Of the sixty-four kilograms of uranium in the bomb,

less than one kilogram underwent fission,

and all the energy of the explosion came from

just over half a gram of matter that was converted to energy.

That is about the weight of a butterfly.”

***

Half-Life of a Secret

by Emily Strasser

University Press of Kentucky; 336 p.

Jesi Bender is an artist from Upstate New York. She is the author of the chapbook Dangerous Women (dancing girl press), the play Kinderkrankenhaus (Sagging Meniscus), and the novel The Book of the Last Word (Whiskey Tit). Her shorter work has appeared in FENCE, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, The Rumpus, and others. www.jesibender.com

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.