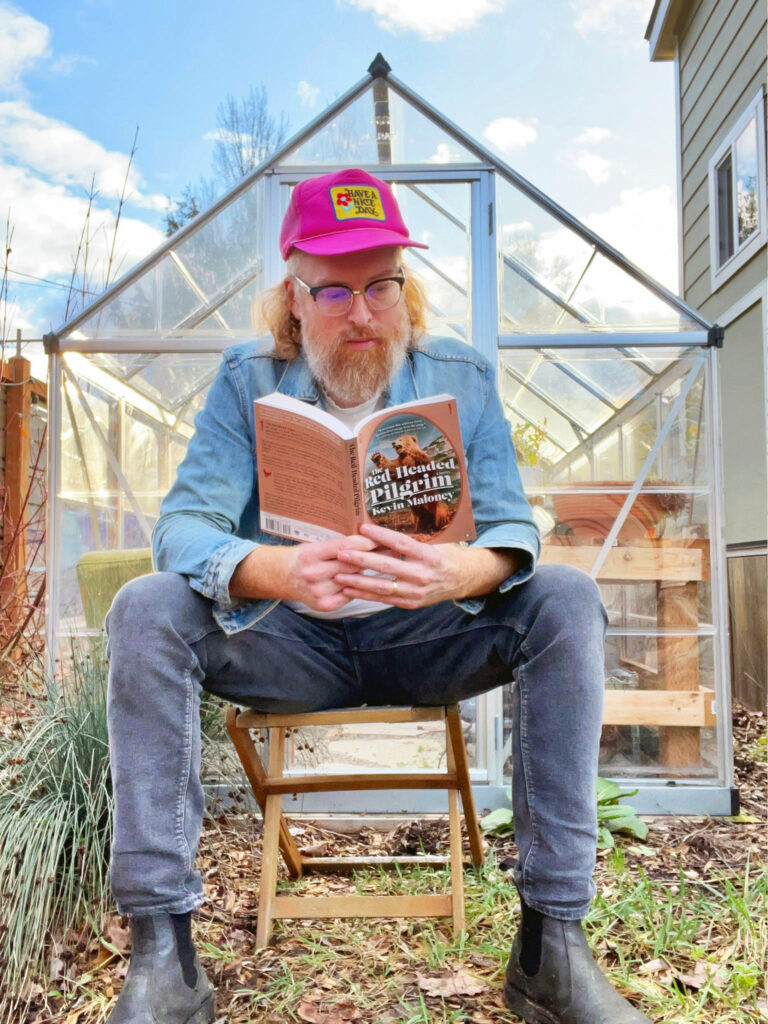

The last time we checked in with Kevin Maloney, it was around the time of the publication of his first book, Cult of Loretta. Now it’s 2023 and Maloney has a new novel out in the world — the fantastic, jarring, comic The Red-Headed Pilgrim. It’s both a comic riff on Maloney’s own life (kind of; see below for more on that) and a genuine tale of what it means to be a pilgrim in the present day (or recent past). It accomplishes the impressive feat of both grappling with some of the biggest issues one can grapple with and of recognizing the folly of taking oneself too seriously. In the middle of a hot summer, I reached out to Maloney to discuss his novel, the role of red in his work, and what’s next for him.

Your novel is called The Red-Headed Pilgrim. You published a story with us called “Wrath of the Red-Eyed Wizard.” Does this mean you’re in your red period? And how do colors — and, more broadly, visual elements — factor into your work?

Ha… I hadn’t thought of that, but maybe? “Wrath of the Red-Eyed Wizard” is one of my favorite story titles I’ve ever come up with, so maybe I was trying to piggyback off of that a little? It’s also a nod to the Willie Nelson album Red Headed Stranger. As a kid, I was teased a lot for having orange hair and freckles, but in my adulthood, it’s a big part of my identity. As a writer, to the extent that I have a “brand,” being a six-foot-six redhead with a mullet is a major part of that. So yeah, this is my red period. Or my orange period. The figure who has most influenced the way I see the world is Vincent Van Gogh, another redhead. Before I was sure whether I wanted to be a painter or a musician or a fiction writer, I read Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo. Those, to me, are the foundational documents for what an artist’s dedication to their craft should look like (even if it pushes them to the brink). I love how colorful Van Gogh’s canvases are. I love the Japanese painters who inspired him—Hokusai and Hiroshige. I don’t know if my novels have a lot of color in the literal sense, but in the way that Van Gogh and the floating world artists of Japan exaggerate color for effect, I think my stories and novels exaggerate reality to make it pop. I want the world in my books to feel like you’re microdosing and the plants are a little more beautiful than usual.

Both this novel and your earlier Cult of Loretta feature a number of characters with obsessive tendencies and a penchant for bad decisions. Unlike your earlier book, the protagonist of this one shares a name and some biographical qualities with you. What prompted you to go the autofiction-adjacent route with this one?

To some extent, Cult of Loretta came right out of my life. It’s set in the suburbs of Portland in the late 90s and follows a bunch of teenagers who are all in love with the same woman and trying to find the meaning of life and keep making bad decisions. That all feels pretty close to my actual life. But when I was 21 or so, I left Portland and traveled to California and Montana and eventually New England, but some of my friends who stayed behind got into some heavier drugs like oxy. A couple of them ended up dead. I wasn’t really around for that, so I think Cult of Loretta was my way of revisiting that time in my life, even though I wasn’t there for the dark part. The drug chapters also gave me a chance to channel my huge Denis Johnson influence, while also using the drugs—in particular the made-up drug “screw”—as a way to write in a magical realist vein. In real life, I’ve only done mushrooms about a dozen times. I smoked a lot of pot in my early 20s, but these days I barely touch it. I drink 2-3 pilsners and try to get a good night’s sleep. I think my goal with The Red-Headed Pilgrim was to see if I could write in the same voice as Cult of Loretta without the dependence on the drug component. I also wanted to see if I could be a little more vulnerable on the page, which led me to writing much closer to my actual life. In terms of bad decisions—I just think that’s what makes a book interesting. Nobody wants to read about the good decisions you made.

It’s probably worth asking if you consider this autofiction, for that matter…

Even though I’ve done quite a few interviews about the book at this point, I just now googled “autofiction” to find out what the term actually means. I guess, yeah, in the sense that certain scenes of The Red-Headed Pilgrim are straight from my life and certain scenes are totally made up, it’s definitely autofiction. It’s been such a buzzword the last few years, usually used in a negative way. If I’m going to be totally honest, I can be pretty out of the loop when it comes to Twitter and “the discourse” and understanding what the hell people are talking about. So many of the books I was influenced by in my youth were thinly veiled autobiography presented as fiction. It didn’t even occur to me that I was positioning myself in a new movement by writing this way. I’m thinking of On the Road and Slaughterhouse Five and Journey to the End of the Night. Books where the arc is close to the writer’s life, but also the writer has total freedom to make shit up. Herman Melville worked on a whaling boat, so to some extent Moby Dick is autobiographical. I don’t think those books are what people have in mind when they’re talking about autofiction, but that’s the tradition I’m trying to write in, and also, in the case of the Beat Generation, make fun of.

The Red-Headed Pilgrim has now been out for a few months. Have you gotten any unexpected reactions from people with respect to the relationship between writer-you and character-you?

Naming my protagonist “Kevin Maloney” was a playful decision—a way to acknowledge and also make fun of certain fiction writers throughout history who created an alter-ego of themselves with a name almost identical to their own. I was like… fuck it, I’ll just give him my name. I’m not going to sue myself. What I didn’t realize is that friends and family who read my book wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between the made-up me and the fictional me. Even my wife sometimes will be like, “Did you actually have a botched menage-a-trois in your early 20s or was that just a scene from your novel?” At my book launch at Powell’s, my buddy Josh was in the audience and asked if, after writing the book, I’ve confused myself about what’s real and what’s made up. I totally have. To some extent we all mythologize our lives. I read an article recently that said that human memory is essentially a story we’re always telling and retelling ourselves, even the moment after something happens, and that the distortions sneak in almost immediately. Those stories are how we figure out who we are.

When drawing more directly from one’s life — I assume, anyway — what’s the process like of revisiting past experiences and trying to figure out what to include and how best to chronicle it?

I don’t write my books in a linear or chronological way at all. Sometimes I don’t know if the thing I’m writing is going to be a story or a novel. I just dive into a time in my life and then try to see where the story takes me. I might say to myself, “I want to write about how hard life was after my kid was born.” Sometimes there was a moment in real life that really captured that, but sometimes it was more of a feeling I had that wasn’t epitomized in a single moment. So, I’ll write a scene that could have happened or that creates a ridiculous, hyperbolized version of a typical day, even though that day never really happened. There’s a scene in Pilgrim where the protagonist comes home from work and finds his wife in tears and their daughter in a pile of laundry crying so hard, she’s throwing up on herself. The protagonist takes his kid for a walk and sings her “Enter Sandman” by Metallica as a lullaby. It’s one of my favorite scenes, but none of that happened in real life. Or maybe, all of it happened. I distilled what that time felt like into a scene. I combined fifty different days into one day and then tried to find the humor in it, even though it’s really sad. For me, it’s just a lot of trial and error trying to get at the scene that captures how things felt. Sometimes the real-life event captures it and sometimes the made-up one does.

The character of Kevin isn’t always the most sympathetic figure; did your relationship to your fictional avatar shift at all during the writing of this?

My biggest fear in writing Pilgrim was that I would point the finger at others and say, “Look at all the bad things people did to me!” I don’t think that makes for a very interesting or self-reflective book. It’s way more interesting to point at yourself and say, “Look at how bad I was. Look at how many mistakes I made. Look at what a fool I used to be. No wait—maybe I still am!” It feels much more compelling and human to make yourself the biggest idiot on the page. But since this is a work of fiction, I tended to push “Kevin Maloney” the character a little further into darkness than what I actually experienced at the time. I drank pretty heavily after my divorce, but I wasn’t the full-blown alcoholic that Kevin the character is. Fictional Kevin smokes opium, which I’ve never done. Fictional Kevin is 30% more self-destructive and nihilistic and angry and aloof than I was in real life, but all those things were in me. I thought it was useful to lean on that in the novel and push those characteristics to an extreme so that the reader understands why the women in the novel—Wendy and Angela—ultimately can’t stand being around him and why his life keeps falling apart.

I see that you have a book due out on CLASH next year — what (if anything) can you reveal about that?

Horse Girl Fever is a collection of my favorite stories I’ve ever published. I’ve revisited some of them and tried to tighten them up and make them more concise and laser focused. I’m trying to keep the collection pretty streamlined. There’s a tendency for story collections to throw everything in there just to fill up space, but my favorite collections, even if the stories aren’t linked, maintain a vibe throughout. Hopefully Horse Girl Fever does that. I want every story to be a banger and have every page excite the reader. The manuscript got accepted by CLASH right around the time Two Dollar Radio accepted Pilgrim. To keep them from tripping on each other, we pushed out the publication date of Horse Girl. I’m looking forward to fine-tuning things with CLASH, maybe throwing another story or two into the mix, rearranging the order, who knows. I haven’t looked at the collection in about a year, so I think I’ll be able to see it with fresh eyes and make sure every story and every page blows the reader away. “Wrath of the Red-Eyed Wizard,” published in Vol. 1, is in the current version and hopefully will stay that way. It’s one of my favorite stories I’ve ever written.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.