Helen Schulman’s Lucky Dogs beguiles readers with its profane bluntness and spellbinding cast as it explores and exposes the misogyny of the Harvey Weinstein trials. Meredith (a fictionalized Rose McGowan) and the victim of Weinstein (“The Rug,”) writes that during the assault, The Rug’s “pubes got in my mouth. I felt that hair on my tongue for like the next six weeks.” Schulman’s instinct to revel in irreverence is part of what makes Lucky Dogs an electrifying read.Nina (a fictional stand-in for Stella Penn Pechanac, the Bosnian spy Weinstein hired to manipulate McGowan) uses her sexuality to get ahead. Tired of being overlooked in her acting class, Nina blows her instructor in order to win his favor (Meredith likewise, on multiple occasions subsequent to the rape, performs oral sex on this sordid producer). Schulman triumphs in her audacious fictionalizing of real-life sexual situations. In holding a brutal lens to rape and the issues that surround it, Schulman breaks new ground by refusing to write another victim narrative. Instead, she seeks to prioritize understanding Nina by bequeathing to her a heartrending backstory. Schulman subverts the typical #metoo narrative by sympathizing with the intelligence agent, who is initially presented as the story’s villain. However, as the narrative progresses, the roles switch and readers are compelled to align themselves with Nina, regardless of their biases prior to reading the book. Schulman’s novel will surprise you–you’ll end up rooting for the villain and disdaining the victim.

Meredith and Nina have a pseudo meet-cute at a Parisian ice cream parlor. After surfing pro-anorexia sites, Meredith buys herself an iced caramel treat, and Nina follows suit. But the night quickly turns frightening when “sweaty and red-faced” American men sexually harass the two women, and Nina pulls out a switchblade, which ends the altercation. As if following a movie script, the women bond over shared trauma while devouring their cones. Nina calls men “cowards with penises,” and Meredith swiftly becomes enraptured with the high-cheekboned, crooked-toothed beauty–she internet stalks her in her Parisian apartment via social media outlets.

To Meredith’s delight, she later runs into Nina in a public restroom, and Nina lures Meredith to a cafe with sturdy tables and elaborate desserts. There, she meets Jean-Pierre–at least that’s the name he gives her–who rocks a Yeezus T-shirt and deftly tears up at the mention of compromised virtue. Jean-Pierre and Nina refill Meredith’s wineglass; they tell her rape stories that may or may not be feigned and aligned with their scheme. Believing the camaraderie is genuine, Meredith discloses her secrets. Nina and Jean-Pierre entice Meredith to become the face of their fictitious women’s organization, Women’s Work, and hand over her precious memoir (Why not? They’re trustworthy, right?). Meredith reflects on this moment: “Why were they both so sexy? Again and again, I fall for the same old scam, as if outer beauty ever safeguarded against inner rot.” Although Meredith clearly views Nina as the “bad guy,” Schulman doesn’t seem to. Promptly after Meredith learns of Nina’s deceit, Schulman pivots to war-torn Bosnia, where Nina was born.

Nina’s childhood abounds with trauma. As an infant, she witnessed her mother’s rape. Persecuted for their Muslim faith, Nina’s family lived in the shadowed basement of a friend’s house, before escaping to Israel. Since she was a young girl, Nina aspired to model and act: she remembers her childhood friend, a girl who wore a pageant “sash” and “high heels” before getting blown up in a massacre. While she lived in the basement, Nina shared a single tube of lipstick with her mother, pining for trendy clothes and fashion mags that she had no access to.

Although Meredith had a rough upbringing–a coke-addicted father and a mentally ill mother–when Meredith and Nina meet, Meredith is living Nina’s dream. Able to travel to Paris on a whim, she otherwise resides in a chicly painted, multi-level house in LA, encircled by a white picket fence and a canoe perched at her doorstep. The house is situated right along the Grand Canal, a setup that she claims, “God designed with me in mind.” When she returns from Paris, Meredith finds that her staff have switched on the AC and adjusted it just so, filled her fridge with healthy meals (which she ends up throwing away), and provided her with a “Welcome Home” basket and a stick of sage to ensure that the vibe of her house is as pleasant as the accommodations. Schulman–perhaps strategically–discloses Meredith’s backstory in hindsight like snippets of memory, while she writes Nina’s backstory in thorough, vivid detail. Whether it was intentional or not, this technique emphasizes the privilege disparity between Meredith and Nina. It makes sense that Nina would despise Meredith, who had all the privilege that Nina desperately wanted. Despite Meredith’s generous tips to taxi cab drivers and cafe workers–and her insistence at her own selflessness for supporting her dysfunctional mother–readers tend to view her as Nina does: privileged and self-absorbed.

Schulman renders Nina a more likable character. The book is divided into sections, alternating between Meredith’s and Nina’s narratives. From page one of Meredith’s section, Meredith’s cutesy, irreverent, simile-rich prose feels phony and histrionic (although it does mimic McGowan’s style of speech). Meredith admits that she wants to be taken seriously, but describes a wine bottle as “wet and phallic and glistening” with “tears of condensation,” and mentions she’s searching for “the existential mother of my soul.” She also doesn’t seem to be telling the truth. Although she swears she didn’t comprehend “The Rug’s” veiled offer, she claims to have had sexual relationships with “high rollers…oilmen from Texas, Silicon Valley zillionaires.” Someone who has a record of profiting off of rich daddies would likely pick up on what it means to join someone else in the shower. Later in the book, Meredith denies ever having done coke, but often describes herself as “stoned” or “drunk”; early on, she tells us she hangs out with “coke-snorting ski bums.”

In contrast, Nina’s sections are written with a matter-of-fact tone, free of any stylistic frills. Schulman is always clear about Nina’s devious tendencies, and at one point she refers to Nina as “[Nina] the liar.” Dipping into Nina’s mind–as she takes pleasure in tricking her mother–Schulman writes: “Someday I will be a world-famous actress. I can convince anyone of anything.” The straightforward third-person narration of Nina’s narrative proves more satisfying than Meredith’s inconsistent and affected prose. Nina is self-contained, and she has an elegance about her: she finds smoking hookah “disgusting,” feels repulsed by one boyfriend’s sexual fluids, and, as a child, meticulously manicured her and her mother’s nails. Meredith, on the other hand, is unrestrained and repelling in her descriptions relating to the body: she gives a detailed description of fiddling with her own drool (will it go in her memoir?) and informs a reporter that she’s “on the rag.” Meredith is very open about her mental health issues: she complains of being suicidal multiple times and suggests that she has bipolar disorder. While it’s plausible that she could have mental health struggles considering her parents’ difficulties–it wouldn’t be surprising if she was putting on airs about the severity of her mental illness (she did lie about the coke accusations). We’re not sure if we can believe Meredith, and her word vomit feels like TMI (although it’s also what makes the book so damn juicy). Meredith, for all her trickery, is gullible in her own right: after she finds out Nina is a spy assigned to take Meredith down, Meredith thinks of Nina as “my girl” and “my sister.” Her own gullibility doesn’t inspire sympathy: if anything, it reduces Meredith’s status and strengthens readers’ view of Nina’s competence.

Replete with sparkling twists, Lucky Dogs is a fascinating narrative puzzle, well-written and expertly crafted. Schulman’s characters are splendidly imagined: they possess the multidimensionality of the human beings who inspired them. Nina is the captivating villain-turned-victim; Meredith is the antiheroine readers will love to despise–rapidly turning pages to the end, while cackling with glee at the outcome (in a calm, literary way). By overthrowing the wounded woman narrative with her literary masterwork, Schulman invites readers to dismantle the imagined, but persistent binary of good vs. evil, and see people, especially our fellow women, for who they are: human.

***

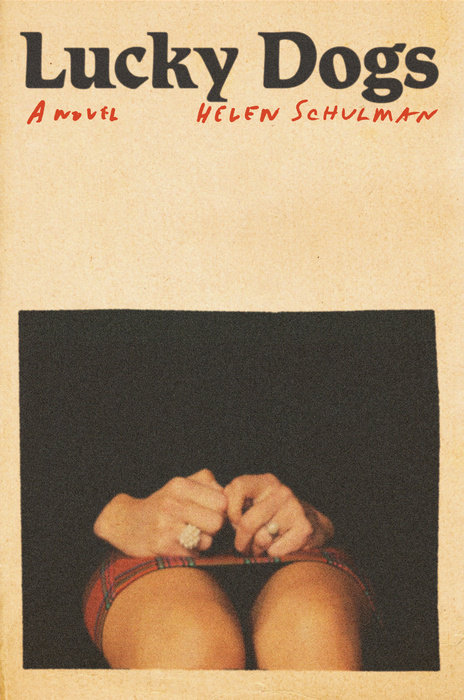

Lucky Dogs

by Helen Schulman

Knopf; 336 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.