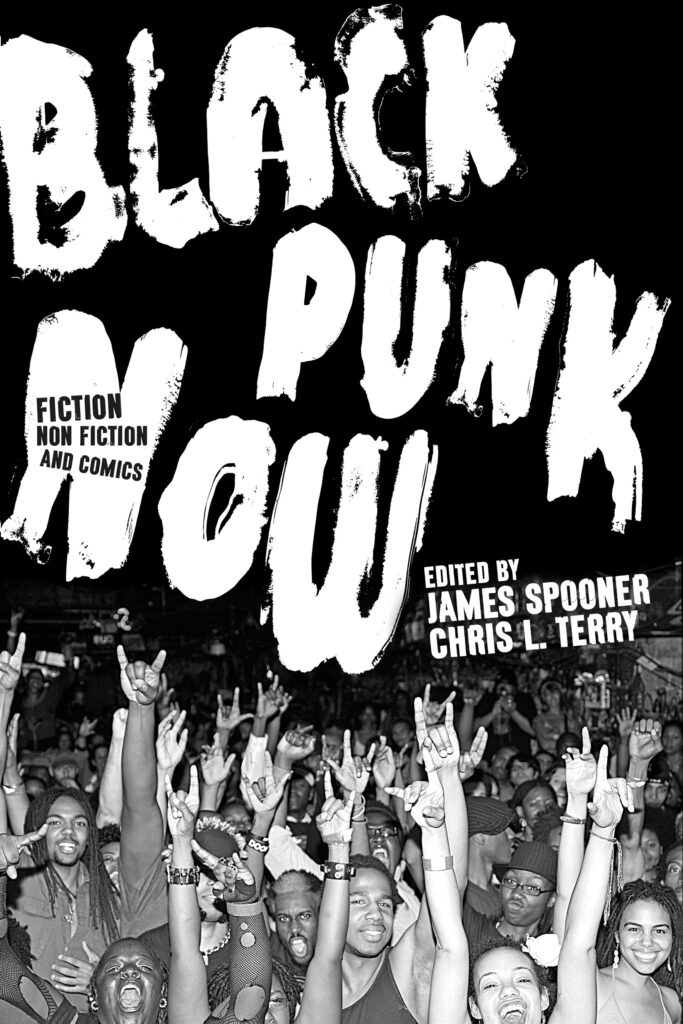

Coming on the heels of Shotgun Seamstress, the collection of zines by the same name edited by Osa Atoe, Black Punk Now — edited by James Spooner and Chris L. Terry — expands the definition of black punk by including many fiction and non-fiction texts, as well as comics. The fiction varies from fantasy to sci-fi to gripping political tales that examine the nature of friendship, identity, and the problem of class structures. The non-fiction texts include essays on how to create DIY zines and how to opt out of the surveillance and policing tactics of the digital age, as well as lyrical pieces that explore grief, pain, and the relationship between the older generation and the younger. Atoe reappears in the book where she interviews the musician and polymath Charlie Valentine, and there is a screenplay for a short film by Kash Abulmalik about young Muslim brothers, one of whom is a punk, and their relationship with their parents. Collectively, all the texts in the book develop our notion of what Black punk is about in all its complexity; politically fierce but tender as well, musically varied, queer, or straight, white or Black; it’s about the new revolution which won’t be televised because it’s off the radar, secretive, nomadic, creative, imaginative, not bound by walls, codes or laws.

Camille Collins’s story “Glow” is about the betrayal of friends and class. The narrator is beaten up by two girls, whom she thought were her friends. The opening line to Collins’s tale is ominous, recalling the days of slavery in the South: “They invited me to my own beating like genteel southern ladies planning an afternoon tea: with a cordial phone invitation to meet up on Sunday.” For economic reasons the narrator and her mother were forced to move from a higher-class to a lower-income neighborhood while her friends stayed behind. She thought at least one of her friends, Alexis, would be loyal. But when the other friend, Kerri, who the narrator wasn’t close to, calls her after a year, and suggests they meet at her house, the narrator is suspicious but decides to go anyway. When she arrives, without warning her “friends” beat her over the head with two science books. She quickly realizes that she made a mistake trusting them and manages to escape. But the narrator ultimately realizes: “Being black means being expendable in America.” Her so-called friends can’t even understand this though they are Black like her. They are comfortable in their “gated communities,” and blind to the facts of the real world. Capitalism says you’ve got to climb that ladder and then you’re a winner. Those left behind don’t matter to those in the ivory tower of “success”: in the White narrative they’re poor because they’re lazy because the American Dream is available to everyone. In the end of the story, the narrator befriends an eccentric White girl at her high school. What the narrator thought was a safe space composed of Black people in fact wasn’t.

In the fairy tale “The Princess and the Pit,” Mariah Stovall also explores the nature of class and acceptance in a community; the tale involves witches and hidden doors to new worlds. The narrator, Xel, lives in a forest with her mother, a witch who protects her. But when Xel turns thirteen, her environment is no longer the same as it was in the past: “the woods are changing. The plants shrivel. The animals disappear” and “the wise woman loses faith in all that she knows.” But then a foreign man appears who wants to “ravish and remake the forest, the beaches on the coast, the world beyond.” Her mother protects Xel from this man by “shoving a tincture down her throat” after which she wakes up in a room with concrete walls and no windows but wooden panels on the floors. Xel discovers a kind of trap door in the floor of this room that leads to a new world of music, and community. In this new space, she is betrayed by a man she thought loved her but is embraced by Nancy, the leader of a punk band. The narrator’s fear of rejection resolves into friendship and a sense of belonging. Stovall writes: “[Nancy] cradles Xel and hushes her wailing. The princess looks up and wipes her snot on the back of her hand. My prince is dead, she whimpers…You’re a monster, she growls at Nancy. So are you, Nancy winks. You’re welcome.” Their femininity is monstrous [i.e. powerful] and against the idea of a “prince” who, in the typical fairy tale, always saves the damsel in distress. No one can save the princess but herself.

Chris L. Terry, in an interview with Brontez Purnell, says: “A nice surprise about working on this book is hearing the ways that people are getting inspiration from past generations on their family. I came in thinking about punk as forever looking for something new, creating something new, fuck the past. And that’s not what we’re really hearing.” In Kash Abdulmalik’s screenplay for a short film, “Let Me Be Misunderstood,” the Hakimah defends her son Talib against his arrogant brother, Enoch. She goes to Talib’s band’s show not only to support her son but because she loves the music: “You guys were amazing, as usual!” Talib’s relationship with his father is more problematic; he is a traditional Muslim who can’t understand punk rock but also a perverse lover of “nasty’ magazines in his old age. Under the guise of tradition lies the pervert. But Talib understands that his father can’t change and neither will he: “Long story short, I ain’t changing him and I don’t want to. I didn’t change who I was for him either, and that was cause I had an anthem and a community.”

In Courtney Long’s “Music Means Free” the narrator visits her father in the hospital and experiences complex feelings. She writes: “I didn’t know I was crying until his eyes got stuck…He has learned to spurt blood with minimal prompting, and I have learned to spurt tears without moving a single muscle.” But out of this experience of grief, music is born; after visiting her father, she drives away from the hospital and blasts music from the car stereo:

I’m leaving behind the smells of hand sanitizer and Lysol wipes with every mile; running away from trailing tubes and ruby vials. I’m screaming at the top of my lungs, remembering the clashing lights, the press of bodies, moshing. For once, I’m screaming at the top of my lungs and not caring who hears me…Sound is everything. Sound vibrates eardrums. Sound is louder than heavy breathing. Louder than heartbeats, louder than thinking. That’s what music means to me.

In this this passage Long captures the complex feelings of youth when confronted with freedom and grief. Finally, in “The Princess and the Pit,” it is when Xel leaves her mother, and her power over her, that her life really begins in all its wonder and excitement. And it is in this communal space where she can develop her own identity. Another aspect of securing your identity against policing and surveillance is learning how to go off the radar.

Black punks have often encountered the forces of dominant powers in the form of police violence and surveillance. The recent murders of George Floyd and Michael Brown are the result of the frequent policing of Black men. But there is also a different kind of war going on in the digital age. In “Opt-Out: Reclaiming Digital Privacy in an Omniscient era,” Matt Mitchell and Ashaki M. Jackson write:

An interesting thing about the modern technology of surveillance is that the weapon is invisible now. It used to be you could see the overseer, you could see the guard in the prison tower. Not it’s debatable whether it exists. One of the hardest parts of my job is explaining that we are under fire by this weapon, because you can’t see it.

We’ve all had the experience of looking up something on Google and then having the subject reappear on Facebook. In their essay, Mitchell and Jackson give some practical advice on “going dark” on the web: “In any app you use, try to use the website, not the mobile phone version because that gets access to other parts of your advice. Your phone is actually a box filled with sensors. The webpage can only get basic web information – what you put into it…Go into personalization, turn that off. Go into Privacy settings, read it, and uncheck stuff….” In a digital war you’ve got to go off the radar. And as Pierce Jordan writes in “A Lyrical Exegesis of Soul Glo’s ‘Jump’ [Or Get Jumped!!!] [[By the Future]”: “You can fight a battle once, but the war takes your whole life.” The DIY aesthetic is also one of the ways to fight this war and is an essential strategy in the blank punk movement.

In the interview with Osa Atoe, Charlie Valentine says about the reason he started a zine: “I made those zines, not because I wanted to make money, but because there was a deep, deep questioning inside me.” It’s not a capitalist venture. Golden Sunrise Collier, in her essay “Big Takeover: Zines as a Freedom Technology for Black Punks and Other Marginalized Groups” writes about one of the main reasons to start a zine:

Firstly, zines are a low-surveillance mode of information distribution; something rare in our increasingly digital age. Ever since we were sold and brought here, Black folk in the United States have been under extreme, life-threatening surveillance, and the rise of the digital era has only made it worse. For all the good the internet does in connecting us, we don’t actually own it and it is a highly surveilled, crypto-fascist, inherently anti-Black informational space.

Community is important and through zines many black punks were able to connect with their peers. Collier writes about zines that “the affordability, anti-authoritarian, low-surveillance aspects of this form align closely with the overall ethos” of DIY. Shotgun Seamstress and Bikini Kill were two of the most important zines to come out of the punk scene, which included texts on activism, social change, queer sexuality, body image, and the discussion of controversial topics such as racism and abuse. But there are countless others being created every day. Zines are an effective strategy in the war against surveillance and policing of ideas. They function off the radar. As Collier writes: “One of the most salient ways that zines operate as a freedom technology for Black folks and other marginalized communities is that they provide a space to speak authentically to our dreams and concerns, circumventing traditional publishing pathways that often tokenize and exclude Black folks (or accept such an extremely narrow topical range beholden to shallow capitalist notions of Blackness and profitability that it is almost entirely inaccessible).” And Collier shows you how to make simple zines by creatively folding a single sheet of paper.

Black Punk Now significantly expands the meaning of what black punk is by highlighting a diversity of opinions and genres; in its pages a reader will find fiction, non-fiction, interviews, a screenplay, comics, all with aim of showing strategies to counter the oppressive racist narratives, and policing tactics that have emerged in the digital era. The book is a call to action. Black punk is not about fixed ideas of sound or aesthetics but rather, as Hanif Abdurraqib writes in “Standing on the Verge,” it is more concerned with “the vast imagination of what punk is, what it has done, and what it can do for people first stumbling into it, and how it can still evolve for those of us who have been immersed in it for years.” Obey the sixth commandment in Joanna Davis’ “10 Commandments of Black Punk According to Matt Davis”: “Be generous with your love.” Start a zine. Build a community. Get involved. Furthermore, Davis writes: “Black punk means liberation, it means doing things for myself, it means family, it means joy, it means healthy rage, it means radical self-acceptance.” Reading Black Punk Now was a revelation to me and opened an exciting new world of sonic pleasures, radical ideas, and stunning visuals. I also discovered some fantastic new writers to pursue. Black Punk is the real deal, and it is the movement of the future; get Black Punk Now (and also Shotgun Seamstress) and find out the reasons why.

***

Black Punk Now

Chris L. Terry and James Spooner, editors

Soft Skull Press; 352 p.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.