Masters of the Nefarious: Mollusk Rampage, the graphic novel by the French artist Pierre La Police, is a colorful, bizarre, hysterically funny book that will delight fans of Brad Neely and Michael Kupperman. The insane plot, which unfurls at a methodical pace of one panel per page, concerns a wave of violent antediluvian mollusks and the trio of furrowed-brow mutants—the twins Chris and Montgomery Themistecles, and their buddy Fongor—who set out to stop them (or not). The Masters of the Nefarious comic originally ran in the French magazine Les Inrockuptibles from 1994 to 1996, before being collected into three French-language volumes over the past several years.

Now, at last, New York Review Comics has published an English-language version of the first volume, Mollusk Rampage. Tasked with wrangling La Police’s uncanny, unpredictable turns of phrase is Luke Burns, a humorist and writing teacher who has been harboring a secret identity as a translator. Burns studied French in college and has spent the intervening years reading and writing it on the sly. With several reader’s reports for NYRC under his belt, and an almost supernatural ability to unearth the funniest way to say something, he was the perfect choice to render Mollusk Rampage for an American audience.

Burns and I met at a café in the West Village to discuss the challenges and joys of translation, how to keep absurd humor from going off the rails, and why the Hardy Boys should be ashamed of themselves. (This interview has been edited and condensed.)

What was the translation process like? Was Pierre La Police involved?

He was. Lucas Adams [the editor] and I corresponded with Pierre, who’s a lovely guy. We had a lot of conversations about what the title was going to be. I was touched by his confidence in me. In talking about whether the humor worked in the book, he felt like I really understood what he was going for, which made me feel good about proceeding with it. We sent him my translation to see if he had any notes on it before we locked in, and he had some very smart, very funny suggestions. He was great to work with.

One thing Pierre said was that it had to be a more creative translation, to capture the tone and the spirit of the original. He didn’t want me to be too literal-minded. Not that I strayed that far from what he wrote, but it was more about the tone of the language, and trying to recreate that was top of mind for me.

What’s an example of a line where the direct translation didn’t match the original spirit of the humor?

“The endgame has begun (maybe).” That was not the literal meaning in the original, but there was a sort of deflating tentativeness to it when it should be this heroic “Time to take out the trash” tone. I don’t think that would have come across in a literal translation.

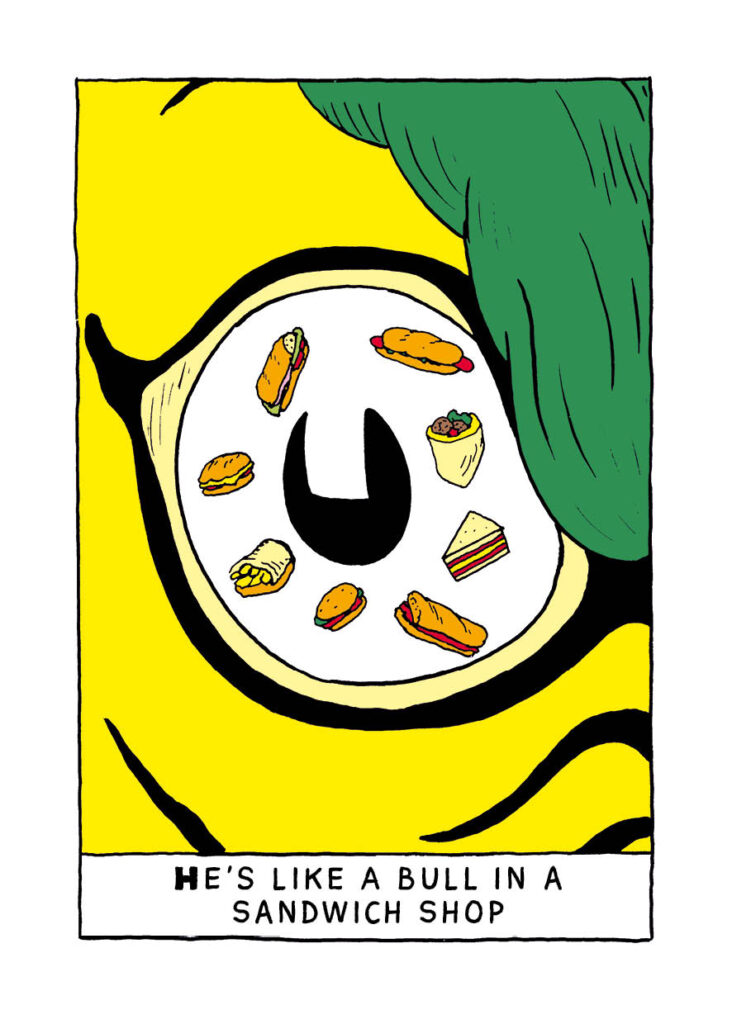

You also had to stray from the literal translation with the sandwich shop line, right?

Yeah, the French phrase for “bloodshot eyes” is les yeux injectés de sang, which means “eyes injected with blood.” It was combined with the French word for sandwiches, which is sandwichs. In the illustration, the character’s eyes are filled with sandwiches. I couldn’t find a way to make that funny in English—it felt a little awkward or forced—so I changed it to “He’s like a bull in a sandwich shop.”

To pat yourself on the back a bit, do you have a favorite word choice in the book?

I really like “burgle the buffet.” Immediately, the first time I read it, I thought that it had to be “burgle.” Very pleased with that one.

How did you decide on “allocates” for the phrase “allocates a right hook”?

Initially I had something more straightforward, like “hits him with a right hook” or “lands a right hook.” After we sent Pierre the translation, he said, “Is there a slightly funnier word we could use here? Something less common.” I sent him a couple of options, and “allocates” was the one. To me it feels very keeping with the original, because the text can be so unexpected after you see the illustration. There’s that sense of discovery.

What was the hardest part of translating this book?

First I should emphasize that I love these books, and I enjoy the work of translation, which is a nice change of pace from generating my own material from scratch. That said, this being my first book-length translation, I really wanted to get it right. One of the nice things about working with Pierre was I knew I would eventually get his signoff, which made me feel more comfortable—but it was also sort of nerve-wracking. He’s somebody I really admire. If he’d come back and said, “I think you missed the mark,” it would have been devastating. So there was that pressure.

Another thing that was difficult was finding the right level of awkwardness in moments that are intentionally awkward in terms of the pacing or phrasing. Imagining a reader who knows that it’s a translation, I was concerned that if something felt too off, it might read as a clunky or overly literal translation. We talked a lot in the editing process about the right amount of comedic grit. As an example, there’s a caption that reads, “Meanwhile, in the real life of the people of today’s modern world.” It’s deliberately clumsy, with way too many descriptors used for comedic effect. I wanted to make sure that you could feel the intention behind a line like that.

You write in your translator’s note that absurd humor is hard to pull off—that, at its worst, it can feel “pointlessly random.” How does La Police avoid this pitfall?

One thing that’s so great about Mollusk Rampage is that there is a logic to the story that anchors you despite all the absurdity going on. While it’s constantly subverting any kind of straightforward narrative, and digressing and going off on these delightful tangents, there is a central mystery that you’re following, even if it often recedes. Not to spoil anything, but I appreciate the payoff that there is somebody behind this evil plot. You can enjoy the book on a panel-by-panel basis, but having those panels woven into a larger narrative makes the story extra-satisfying.

The other thing I will say, in terms of the way it’s absurd but stays on the rails and feels earned, I think that the formal consistency of it gives it a real grounding. It’s always one panel and a single caption below it. For the reader, even as things are getting wacky, you at least know what to expect visually.

In your note, you also say that juxtaposition and surprise are a big part of why the book is so funny. What else makes it work?

The expressions on the characters’ faces—they look so dumb, but they’re also taking everything so seriously. There’s some good acting on their part. They’re so committed (not to describe them as if they’re real people), and they have an intensity in response to every stupid thing that comes their way. Our heroes have that serious-mindedness that you often find in comics or adventure stories.

They get really mad, sometimes beating people to death over trivial offenses.

I think that the random and casual violence that pops up is an interesting critique on characters like Batman and Dick Tracey, and certain stories that I would read as a kid, like Hardy Boys and Tom Swift. They’d clock someone on the head with a rock, and you’d think, Damn, you messed that guy up. He’s probably going to wind up in the hospital. But we accept it as readers because of the trope-iness of it.

I don’t know if this was Pierre’s explicit intention, but I also think it’s a commentary on comic book narratives and superhero stories. Reading one issue of X-Men at a time as a kid—I could never get a decent run going, I was always picking up random issues—I think something this book captures with its digressions is that feeling of, “Wait, what is this? They’re on some island? I don’t know what’s going on.” And with characters dying and then coming back to life, having that presented as a normal type of storytelling, it really draws attention to the ridiculousness of it.

Is there anything you’d like to add?

I hope this book finds an English-speaking audience. I think for the right type of person—and this was my experience—this book will hit so hard. I hope it reaches those people.

There are three volumes of Masters of the Nefarious, all of which blew me away. I actually just, for my own enjoyment, started translating the second volume.

Follow Vol. 1 Brooklyn on Twitter, Facebook, and sign up for our mailing list.